Sommaire

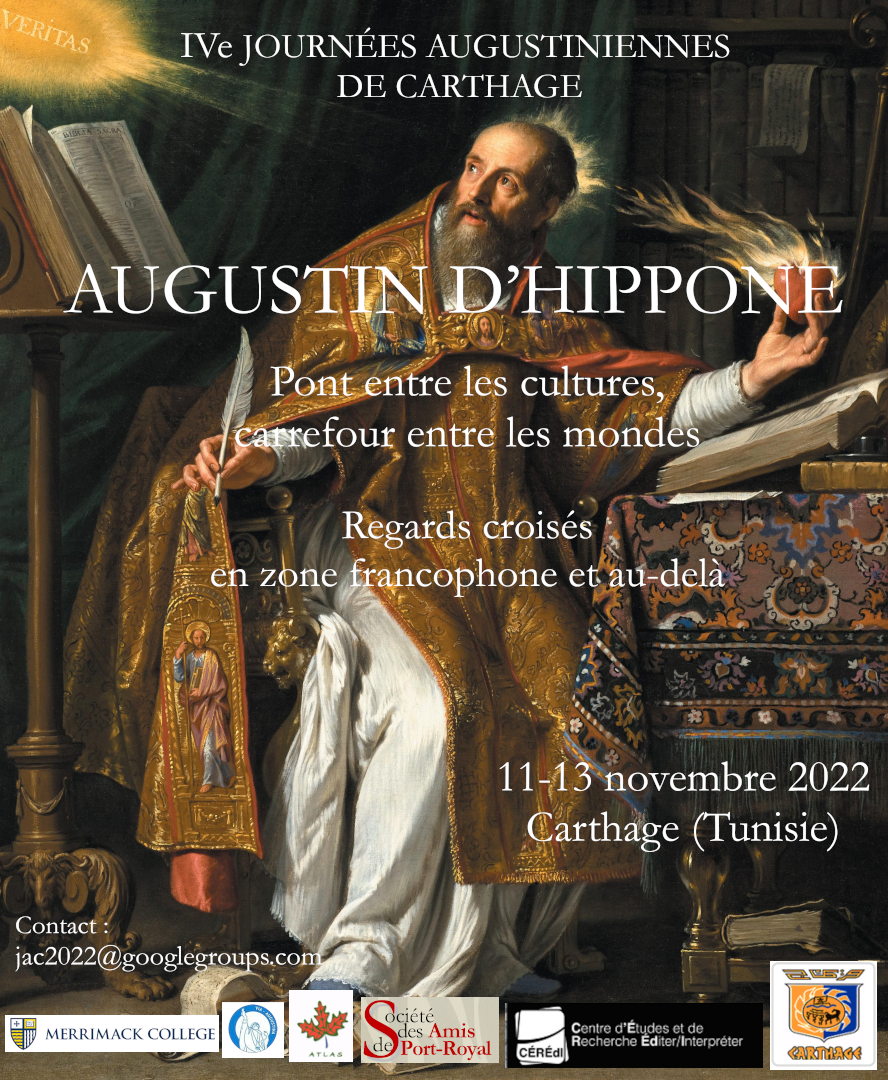

Augustin d’Hippone. Pont entre les cultures, carrefour entre les mondes

Regards croisés en zone francophone et au-delà

Actes des IVe journées augustiniennes de Carthage (11-13 novembre 2022).

Textes réunis par Tony Gheeraert.

- Tony Gheeraert Avant-propos. Saint Augustin, randonneur du sens

- Zahia Amara Saint Augustin et la critique de l’idolâtrie : sur les pas des congénères

- Anja Bettenworth Augustine in the underworld – the presentation of Augustine in non-Augustinian texts

- Moritz Kuhn La mise en scène de l’africanité de saint Augustin dans la Vie d’Augustin de Possidius de Calame

- James K. A. Smith Between Augustine and Hegel: History as the Smuggler of the Spirit

- Pierre Descotes Une anti-confession : La Chute d’Albert Camus

- Anthony Glaise De la Cité de Dieu à la Terre du Milieu. Pour une lecture augustinienne de J. R. R. Tolkien

- Mohamed Bernoussi Présence du corpus augustinien dans l’œuvre d’Umberto Eco

- Laurence Plazenet « Nous lisons toujours saint Augustin avec transport » : les traductions de l’évêque d’Hippone et Port-Royal

Augustin d’Hippone. Pont entre les cultures, carrefour entre les mondes

Between Augustine and Hegel: History as the Smuggler of the Spirit

James K. A. Smith

This paper argues that key aspects of Augustine’s theology of providence are smuggled into modernity by means of Hegel’s philosophy of history. For both Augustine and Hegel, history itself is a passeur of the Spirit, a sacramental mediator of divine presence and action, a smuggler of Geist. This is why both theology (Augustine) and philosophy (Hegel) must take up history as Sache; history is a text to be read in order to understand what the Spirit is saying, or better what the Spirit is doing. History has an almost sacramental quality of mediating divine intention and action. My secondary aim, as an exercise in intellectual history, is to demonstrate why Hegel’s philosophy of history might be the most faithful extension of Augustine’s theology of history, even if Hegel rarely cites Augustine. We might playfully suggest that Hegel is a passeur of Augustine into modernity insofar as key Augustinian intuitions about the entwining of God and history are “smuggled” into modernity in Hegel’s philosophy of history. As a creative repetition of Augustinian themes, we could argue that Augustine’s theology of history is smuggled onto the shore of modernity by Hegel, his ferryman. Thus we moderns are more Augustinian than we might realize.

1In a 1948 interview, Algerian writer Albert Camus, who wrote his dissertation on Neoplatonism and Augustine, reflected on a perceived dichotomy between Augustine and Hegel. He described the dichotomy this way:

We do not believe any longer in God, but we believe in history. For my part, I understand well the interest of the religious solution, and I perceive very clearly the importance of history. But I do not believe in either one or the other, in an absolute sense. I interrogate myself and it annoys me very much that we are asked to choose absolutely between Saint Augustine and Hegel. I have the impression that there must be a supportable truth between the two1.

2Framed in this way, Augustine and Hegel stand for two different accounts of meaning or significance, two different ways of making sense of our experience, two different sources of hope: either God or history2. This is a story about modernity that some strains of the Enlightenment like to tell: we used to place our hope in God, now, in our disenchanted world, we trust the engine of history.

3To his credit, Camus refuses the dichotomy. He wants to live between Augustine and Hegel. But Camus too readily accepts this story about Hegel; that is, Camus accepts the notion that history in Hegel’s philosophy is essentially naturalistic, an immanent force at work in the world instead of God.

4But this is a fundamental misreading of Hegel. In fact, as I will argue, there is little if any room “between” Augustine and Hegel. Or, perhaps better, as a modern extension of Augustinian intuitions, Hegel’s philosophy represents the between that Camus might have been looking for precisely because, for Hegel, God’s Spirit is incarnate in history.

5Indeed, like Camus, in fact, both Augustine and Hegel would themselves refuse any false dichotomy between an appeal to God or an appeal to history. To the contrary, both Augustine and Hegel see history as an arena of God’s action such that to “read” history is “apocalyptic” insofar as it unveils God’s presence and purpose in time. More specifically, both Augustine and Hegel read history as a conduit of the Spirit’s activity – and not just the “providential” activity of sustaining creation but the redemptive activity of reconciling the cosmos and human community with the divine. Both Augustine and Hegel operate on the basis of a conviction well-articulated by the Latin American theologian Gustavo Gutiérrez: “God’s temple is human history3.” For both Augustine and Hegel, history itself is a passeur of the Spirit, a sacramental mediator of divine presence and action, a smuggler of Geist. This is why both theology (Augustine) and philosophy (Hegel) must take up history as Sache; history is a text to be read in order to understand what the Spirit is saying, or better what the Spirit is doing. History has an almost sacramental quality of mediating divine intention and action.

6My secondary aim, as an exercise in intellectual history, is to demonstrate why Hegel’s philosophy of history might be the most faithful extension of Augustine’s theology of history, even if Hegel rarely cites Augustine. We might playfully suggest that Hegel is a passeur of Augustine into modernity insofar as key Augustinian intuitions about the entwining of God and history are “smuggled” into modernity in Hegel’s philosophy of history4. As a creative repetition of Augustinian themes, we could argue that Augustine’s theology of history is smuggled onto the shore of modernity by Hegel, his ferryman. Thus we moderns are more Augustinian than we might realize5.

7I will begin by rehearsing key aspects of Augustine’s account of providence and then explore how Hegel’s philosophy is the Aufhebung of Augustine in this regard – at once taking up and superceding a doctrine of providence by deepening and expanding the pneumatological aspect. Thus pneumatology is crucial to both Augustine’s and Hegel’s accounts of history. Their philosophies of history are, ultimately, pneumatologies precisely because history is understood to be a mediator of the Spirit, a bridge for reconciling God and the cosmos. This paper explores the parallels between Augustine’s and Hegel’s Christological reading of history in order to demonstrate that, contra Camus, we need not choose between them because they both agree that history itself is the between of God, the arena of divine mediation.

Augustine on Providence

8Augustine’s City of God is an extended exercise in what we might describe as temporal orientation – a ranging exploration of when we are in order to guide how we are and how we respond to the vicissitudes of history. The exercise is grounded in something like Gutiérrez’s conviction that human history is God’s temple, and Augustine is interested in the particulars – the nooks and crannies, the zigs and zags, the events and episodes of the ancient past and the calamitous present in which he believes God’s providence is at work. In all of this, Augustine believes, there is something for us not only to learn but to carry. You have to listen for the whispers, Augustine counsels, because “divine providence controls even the lowest things on the earth, producing as evidence all the thousands of beauties found not only in the bodies of living creatures but even in blades of grass6.” This is not a puppet-master picture of providence but rather a sense of God’s Spirit as the breath of all creation, infusing, inspiring, sustaining, moving.

9To read history in such a way is a risky endeavor for creatures because God’s providence is “a profound mystery7.” It is risky also because it requires a degree of concretion and specificity; we always read history from a time and place. It can be easy to conflate “reading for providence” with an exercise in theodicy, as if trying to discern the Spirit’s movements in history is the same as justifying that history. Trying to see where the Spirit is afoot in his moment, witnessing the waning of the Roman Empire from the shore of North Africa, Augustine’s project is very specific and reflects his location: “Let us therefore proceed to inquire why God was willing that the Roman Empire should extend so widely and last so long8.” The exercise requires “us to go on to examine for what moral qualities and for what reason the true God deigned to help the Romans in the extension of their empire; for in his control are all the empires of the earth9.” It would be too hasty to conclude that Augustine is justifying the Roman Empire or providing an account of how God “blessed” it. To the contrary, Augustine’s critique of Rome is trenchant: Rome, in his estimation, could only ever be unjust10. The question isn’t about justifying the current regime; it is about discerning a way forward: when are we, what are we inheriting, what must we undo, what can we hope for, given this history? What has the Spirit given us in history? How has God turned evil for good (De civ. 11.17) and leveraged the machinations of an unjust empire in order to accomplish God’s purposes in the world? To answer such questions requires attention to specifics of time and place (which is why our students today struggle with so much of City of God, precisely because it is so embedded in its context).

10Around the same time that City of God made its way to readers, Augustine took up the theme of providence in a letter to Marcellinus (ep. 138). In this context, Augustine emphasizes the mutability of God’s interactions with humanity across time. This is not because of any change in God but rather given the change, even evolution, of humanity. Augustine compares both “the natural world” and “human activity” in this respect: both, he says, “are subject to change according to a system fixed in accordance with appropriate seasons. However, the system that governs their changes is not subject to change itself” (ep. 138.2). The unchanging guidance of providence finds its expression in changing manifestations and expectations given when creatures are. While the farmer’s “systems of agriculture” don’t change – the farmer always aims to husband the land and animals –precisely because of that steadfast goal the farmer nonetheless does different things depending on the season. So, too, the immutable God’s revelations, expectations, and interactions with humanity change over time. “[I]t does not mean that God is changeable”, for example, “if he required a different offering in the earlier stages of the unfolding of the world’s history from the latter” (ep. 138.7). It’s not that God is “fickle” (ibid.); rather, as history “unfolds,” as humanity develops, as new possibilities emerge given the unfolding of history, new modes of God’s self-revelation become both possible and necessary.

11Augustine offers an aesthetic parallel, invoking a standard distinction in the rhetoric of his day, distinguishing “the beautiful” and “the appropriate” (or what’s “fitting”). “The Beautiful,” on Augustine’s rather Platonic take, has an idealism about it that is not subject to time: “the beautiful is assessed by itself and praised” (ep. 138.5); it has an objectivity and universality about it that is independent of context. “The Appropriate,” however, by definition depends on something else. It is with reference to a time and place that we judge what is fitting. The appropriate is always contextual.

12While God is eternal and immutable, insofar as God loves and relates to mutable human creatures, God’s economy is more like The Appropriate than The Beautiful. Commenting on altered standards of worship and sacrifice, for example, Augustine says “Now… God has commanded something else, appropriate for the present period; and he understands far better than the human race what is most suitable to provide for each age, what and when he – the unchanging Creator, the unchanging governor of the changing world – should grant something or add something” (ep. 138.5). Not until the end of history, Augustine hints, will we be able to recognize the Beauty of this. “Then, finally, the beauty of the entire temporal universe, with its individual parts each appropriate to its time, will flow like a great song by some indescribably great composer” (ep. 138.5).

13In the meantime – which is to say, while we are still in the midst of history’s unfolding, before the culmination of history – the exercise undertaken in City of God could be seen as an attempt to listen for the melody of the Spirit in media res, while we are pilgrims on the way. This is the work of discernment in order to know how to answer God’s call in the present.

Hegel: Spirit of/in History

14Hegel ends his Lectures on the Philosophy of World History with the same question of discernment: “[I]t is spirit that bears witness to spirit, and in this way it is present to itself and free. What is important to discern is that spirit can find freedom and satisfaction only in history and the present – and that what is happening and has happened does not just come from God but is God’s work11.” This is the overarching goal of Hegel’s entire philosophy of history: to discern the shape of God’s work in history through reading the “shapes” of the Spirit in human culture. Hegel’s project does not merely appeal to a providence in order to assure some vague point about God’s “control” of history; rather, it is in the movement of history and the development of human societies that we discern what God is doing and the end toward which the Spirit is shepherding the world. By reading history we discern what God wants for the world.

15The basic assumption and animating conviction that drives Hegel’s philosophy of history is that “reason governs the world” (LPWH, 79). However, in order to appreciate the theological nature of this assumption, we must recall that, for Hegel, reason is the outworking of Geist, Spirit, which is, fundamentally, God12. World history “is the rational and necessary course of world spirit. World spirit is spirit as such, the substance of history, the one spirit whose nature [is] one and the same and that explicates its one nature in the existence of the world. This, as we have said, must be the result of history itself” (LPWH, 80-81). But Hegel is not satisfied with a vague or blanket claim in this respect; rather, the conviction compels a more careful attention to the specific details of history. We cannot content ourselves with sweeping appeals to the tapestry; we must attend to the specific warp and woof when looking for the Spirit’s manifestations. History, Hegel emphasizes, “must be taken as it is; we must proceed in a historical, empirical fashion.” Hence “our first condition” in such an exercise is “that we must apprehend the historical accurately.” (LPWH, 81).

16And yet what the details of history mean cannot be simply “read off” the surface by means of journalistic reporting. “The truth does not lie on the superficial plane of the senses; in regard to everything that aims to be scientific, reason may not slumber and must employ meditative thinking (Nachdenken)13” (LPWH, 81). Reporting on the events that comprise the French revolution is not a philosophical history; rather, Hegel brings a different question: How is Spirit afoot in such events? What is revealed? What is God doing here? What does this reveal about the telos of humanity?

17Undergirding this is a distinct conception of the relationship, even entwinement, of God and humanity. Hegel’s Geist is expansive and overflowing. Thus Hegel uses Geist and its cognates to refer to several different aspects of history. Sometimes Geist is the world spirit, the very substance of the cosmos – in short, God as Spirit. But humanity, created in God’s image with rational powers of reflection, is also spirited14. This is why the history of human culture, the manifestation of human spiritedness (particularly in contrast to animality) is, at the same time, the arena of God as Geist. In other words, Hegel’s philosophy of world history is a radically incarnational account in which God’s Spirit is “descended” into humanity’s spirit across human history. The unfurling and unfolding of human culture is the unfolding work of God across time. We might say that Hegel’s sense of the spiritedness of human history is akin to Augustine’s doctrine of the totus Christus; but now God’s presence in a social “body” is wider than the ecclesia and extends as far as human history itself.

18Thus the reflective, meditative (Nachdenkenisch) work of philosophical history, which reads and discerns the movements of the Spirit in human cultural activity, is “speculative,” not in the sense of being an inventive conjecture but rather in the sense of the mirroring of spirit / Spirit. We look into our history as in a mirror and, if we have eyes to see, we see the face of God looking back. “Whoever looks at the world rationally sees it as rational too; the two exist in a reciprocal relationship” (LPWH, 81).

19If Hegel is critical of the doctrine of providence in this context, it is not because he rejects the notion that God superintends history, but rather because too many Christian appeals to providence settle for a vague, abstract conviction about this and refuse to “get into specifics.” Claims about “faith in providence,” in Hegel’s terms, settles for remaining “general and does not advance to the determinate.” In other words, too many Christian appeals to providence aver to the “mystery” of it all and conclude that God’s plan is “hidden from our eyes15” (LPWH, 84). But for Hegel, this amounts to spurning a source of revelation.

20Hegel does not reject the doctrine of providence; rather, he means to advance it to the level of the “concrete.” “We cannot, therefore, be content with this petty commerce, so to speak, on the part of faith in providence, nor indeed with a merely abstract and indeterminate faith that concedes the general notion that there is a providence ruling the world but that does not apply it to specific [events]. Rather, we must be serious about [our faith in providence]” (LPWH, 84). For Hegel, getting serious about providence means getting determinate, risking a reading of specific events in human history16. Indeed, for Hegel the compulsion to know God translates into the duty to reflectively understand history. His commentary on this point is a succinct summary of the very core of Hegel’s philosophy:

In the Christian religion God has revealed godself; i.e., God has given it to humanity to know what God is, so that God is no longer hidden and concealed17. With the possibility of knowing God, the duty to do so is laid upon us. The development of the thinking spirit, which starts out from and is based on the revelation of the divine being (Wesen), must eventually increase to the point that what initially was set before spirit in feeling and representational modes is also grasped by thought. The time must finally come when this rich production of creative reason – which is what world history is – will be comprehended. Whether the time has come for this cognition will depend on whether the final purpose of the world has ultimately entered into actuality in a universal and conscious manner. This [is] the understanding of our time. Our cognition consists in gaining insight into the fact that what is purposed by eternal wisdom comes about not only in the realm of nature but also in the world of actual [human events] and deeds18 (LPWH, 85).

21We see that, for Hegel, attending to history is ultimately a theological exercise. Because God’s self-revelation has made it possible to know God, we have an obligation to seek such knowledge. And insofar as God reveals Godself in history, our compulsion to seek God is enacted as philosophical history, the meditative, speculative exercise of discerning Spirit in the unfolding of human history and culture. If history hinges on God’s self-revelation in the Incarnation, God’s descent into time in the incarnate Son, and the subsequent sending of the Spirit, makes it possible for humans to now read history itself as an arena of revelation19.

22And what does Spirit want? If we read human history closely in this way, what do we discern as the “final purpose” of the world, the telos of human history?

23For Hegel, the unfolding of world history is aimed at an end which can be described in two ways, as either freedom20 or reconciliation21. These are two names for the same telos. Insofar as alienation and estrangement hamper our freedom and self-awareness, overcoming alienation effects, at once, both reconciliation and liberation. But that means Hegel is attuned to all of the modes of estrangement and alienation that characterize human history – which is just to say, as the young Hegel famously put it, history only arrives at Easter by going through Good Friday.

24Here is where Hegel’s Spirit is a smuggler (passeur). Part of what Hegel calls “the cunning of reason22” is Geist’s capacity to covertly leverage and deploy the passions and interests of human actors in order to accomplish history’s ends, viz., the consciousness of freedom. “The vast number of volitions, interests, and activities constitutes the instruments and means by which the world spirit accomplishes its purpose23” (LPWH, 93). As such, “the actions of human beings in world history produce an effect altogether different from what they intend and achieve, from what they immediately love and desire (94). This is a philosophical rendition of Genesis 50:20: “you meant evil for me, but God meant it for good.” This is not a hasty “justification” of evil. Hegel does not shrink from recognizing the tragedy of suffering. “But even as we look upon history as this slaughterhouse in which the happiness of peoples, the wisdom of states, and the virtues of individuals are sacrificed, our thoughts are necessarily impelled to ask: to whom, to what final purpose, have these monstrous sacrifices been made?” (LPWH, 90) As the editors of the English edition of his Lectures on the Philosophy of World History comment: Hegel’s “vision is ultimately tragicomic, for good does come out of evil, however imperfectly, and reconciliation is accomplished through conflict” (LPWH, 17). This is not a blithe instrumentalization of human suffering that then happily celebrates its outcomes. It is rather a cruciform account: it is to look at history, we might say, with the eyes of Mary in Michaelangelo’s pietà. The same heart that wondered at the Nativity here looks upon the lifeless body of her Son and wonders: what could come of this? What is God doing? The answer, of course, is resurrection: the death of death in the death of Christ. This, too, would be liberation – freedom from death’s sting.

Conclusion

25There are many ways that Augustinian insights and intuitions have been smuggled into modern consciousness, covertly and even unconsciously. The intellectual legacies of Pascal, Heidegger, Camus and others have seeded Augustinian ideas in modern human consciousness. I am suggesting that, surprisingly, we might add Hegel to their number. His philosophy of history, though showing little surface debt to Augustine, in fact extends and deepens the Augustinian theology of providence. With Camus, we can refuse to choose between Augustine and Hegel because we refuse the false dichotomy. Perhaps, unlike Camus, we might even begin to entertain what Hegel and Augustine share: hope.

1 Albert Camus, “Interview à Servir” (1948), in Œuvres complètes II 1944-1948, Paris, Gallimard, 2006, p. 659. Cited in Matthew Sharpe, “Albert Camus’ Hellenic Heart, between Saint Augustine and Hegel,” in Brill’s Companion to the Reception of Classics in International Modernism and the Avant-Garde, Leiden, Brill, 2017, p. 242.

2 This, we suspect, was the choice as framed by Camus’ Marxist contemporaries, whom he frequently disappointed.

3 Gustavo Gutiérrez, A Theology of Liberation, rev. ed., trans. Sister Caridad Inda and John Eagleson, Maryknoll, NY, Orbis, 1988, p. 115. It should not surprise us that Gutiérrez’s somewhat Hegelian endeavor announces its Augustinian debts from the beginning when he holds up a model of “theology as critical reflection on praxis”: “The Augustinian theology of history which we find in The City of God… is based on a true analysis of the signs of the times and the demands with which they challenge the Christian community” (ibid., p. 5).

4 Mediated in part by the theological sources of the Protestant Reformation (led by the Augustinian friar, Martin Luther) that shaped Hegel’s theological training.

5 I develop this account of a kind of “covert” or subterranean Augustinianism in modernity in James K. A. Smith, On the Road with Saint Augustine, Grand Rapids, Brazos Press, 2019, chap. 2.

6 Saint Augustine, The City of God 10.17, trans. Henry Bettenson, New York, Penguin, 1984, p. 397-398.

7 Augustine, City of God 1.28, 39. We will see below that Hegel is critical of such invocations of providence that settle for abstraction in the name of “mystery”.

8 Augustine, City of God 5.preface, 179.

9 Augustine, City of God 5.12, 196.

10 For Augustine, there can be true justice only where there is true worship. Since the pagan empire, as an outpost of the earthly city, could never be a site of true worship, it could never be home to true justice. However, that doesn’t prevent Augustine from nonetheless affirming the goods of the empire which, relatively speaking, are preferable to anarchy. For discussion, see City of God 19.21-25, 881-891.

11 G. W. F. Hegel, Lectures on the Philosophy of World History, vol. 1: Manuscripts of the Introduction and the Lectures of 1922-1923, ed. and trans. Robert F. Brown and Peter C. Hodgson, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 2011, p. 521. Hereafter abbreviated in text at LPWH.

12 One might suggest that Hegel’s notion of Spirit as that which animates and governs culture as analogous to the role of rationes seminales in Augustine’s theology of nature. For a relevant discussion, see Gerald P. Boersma, “The Rationes Seminales in Augustine’s Theology of Creation,” Nova et vetera 18, 2020, p. 413-441.

13 On Nachdenken as a mystical element in Hegel’s thought, see editor’s note in LPWH, 14n.27.

14 Some contemporary, more naturalistic, readings of Hegel (e.g., Robert Brandom, Robert Pippin) construe humanity’s geistlich character as “mindedness”.

15 Cp. Hegel’s similar critique in Elements of the Philosophy of Right, ed. Allen W. Wood, trans. H. B. Nisbet, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1991, § 343.

16 In this context Hegel emphasizes that this is precisely why philosophy cannot avoid religious truths. If philosophy is going to take history seriously, it will have to face God (LPWH, 85).

17 This is Hegel’s subtle critique of those who appeal to “hiddenness” with relation to providence. Cf. the dynamics of 1 Cor. 2:9-10 (“… these things God has revealed to us through the Spirit”). While Augustine mentions the “mystery” of God’s providence, the exercise of City of God is also clearly an attempt to “get specific” and read determinate history in order to discern God’s activity in human history and culture.

18 Cp. Elements of the Philosophy of Right, §342: “since spirit in and for itself is reason, and since the being-for-itself of reason in spirit is knowledge, world history is the necessary development from the concept of the freedom of spirit alone, of the moments of reason and hence of spirit’s self-consciousness and freedom. It is the exposition and the actualization of the universal spirit.”

19 Much time has been spent focused on the question of whether Hegel thinks we have arrived at the so-called “end of history,” in terms of our ability to see all of this. I do not have space here to enter into this debate, but suffice it to say that, contrary to dismissive readings, I do not think Hegel believes we have “arrived” in this respect.

20 “World history is the progress of the consciousness of freedom” (LPWH, 88).

21 On reconciliation, see, for example, LPWH, 85-86 (not to mention the culmination of Phenomenology of Spirit).

22 LPWH, 96n.44.

23 Part of the history of consciousness, as Hegel tells it, is the emergence of consciousness from its subjection to nature and its drives, developing into consciousness interests and volitions, and eventually to a form of self-consciousness that recognizes the difference between the two (cp. LPWH, 93; also rehearsed in PhG). For Hegel this is a story of humanity’s emergence from the “immediacy” of nature to the liberating power of “mediation” in which, by means of the reflexive power of reason, we see and know and understand our situation, granting us agency and freedom (cp. LPWH, 103). Meditation, i.e., becoming reflexively aware, is a kind of power that engenders our agency in history. This is the self-transcendence of spirit: “the spirit whose theater, property, and field of actualization is world history is not one that drifts about in the external play of contingencies but is rather a spirit that is itself the absolutely determining [power]; its own distinctive determination stands firmly against contingencies, which it makes use of and governs [for its own purposes]” (LPWH, 108).

Actes des IVe journées augustiniennes de Carthage (11-13 novembre 2022).

Textes réunis par Tony Gheeraert.

© Publications numériques du CÉRÉdI, « Actes de colloques et journées d’étude », n° 30, 2024

URL : http://publis-shs.univ-rouen.fr/ceredi/index.php?id=1638.

Quelques mots à propos de : James K. A. Smith

James K. A. Smith is professor of philosophy at Calvin University in Grand Rapids, Michigan, USA. He is the author of a number of books including Jacques Derrida: Live Theory (2005), Who’s Afraid of Postmodernism? (2006), How (Not) To Be Secular: Reading Charles Taylor (2014), On the Road with Saint Augustine (2019), The Nicene Option: An Incarnational Phenomenology (2021), and How to Inhabit Time (2022).