Sommaire

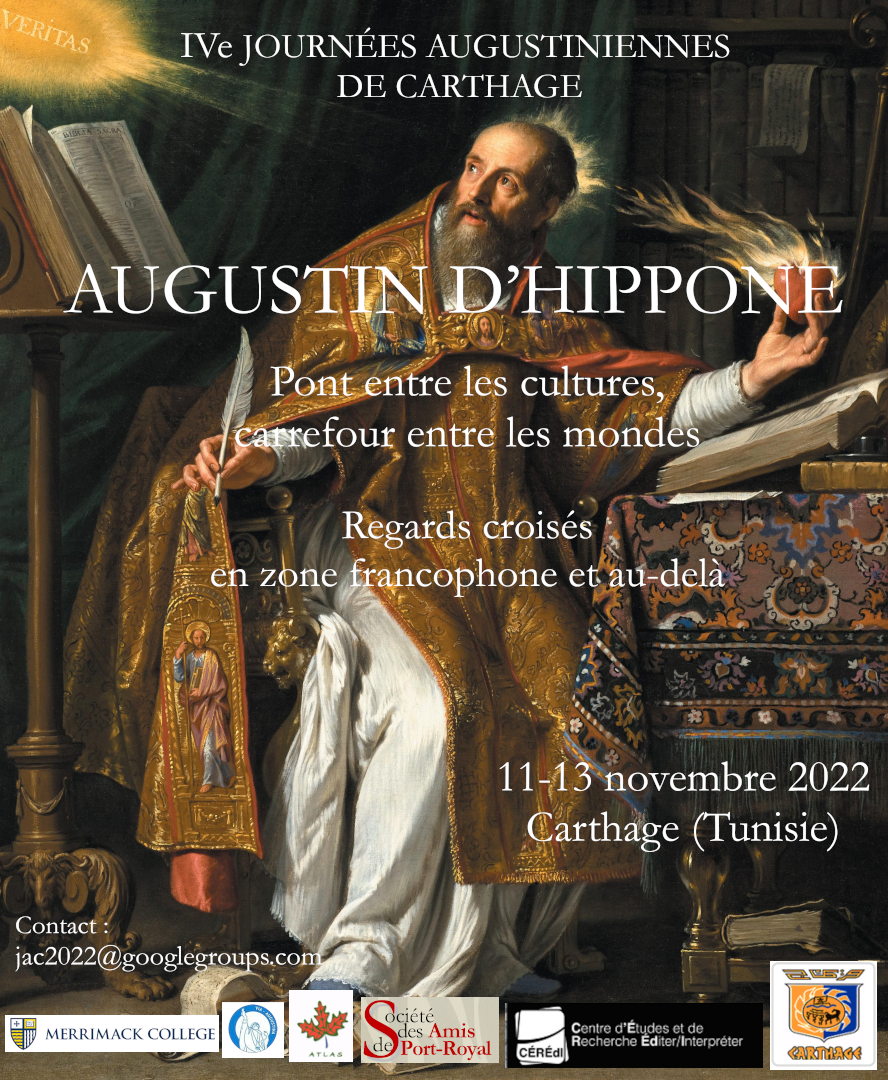

Augustin d’Hippone. Pont entre les cultures, carrefour entre les mondes

Regards croisés en zone francophone et au-delà

Actes des IVe journées augustiniennes de Carthage (11-13 novembre 2022).

Textes réunis par Tony Gheeraert.

- Tony Gheeraert Avant-propos. Saint Augustin, randonneur du sens

- Zahia Amara Saint Augustin et la critique de l’idolâtrie : sur les pas des congénères

- Anja Bettenworth Augustine in the underworld – the presentation of Augustine in non-Augustinian texts

- Moritz Kuhn La mise en scène de l’africanité de saint Augustin dans la Vie d’Augustin de Possidius de Calame

- James K. A. Smith Between Augustine and Hegel: History as the Smuggler of the Spirit

- Pierre Descotes Une anti-confession : La Chute d’Albert Camus

- Anthony Glaise De la Cité de Dieu à la Terre du Milieu. Pour une lecture augustinienne de J. R. R. Tolkien

- Mohamed Bernoussi Présence du corpus augustinien dans l’œuvre d’Umberto Eco

- Laurence Plazenet « Nous lisons toujours saint Augustin avec transport » : les traductions de l’évêque d’Hippone et Port-Royal

Augustin d’Hippone. Pont entre les cultures, carrefour entre les mondes

Augustine in the underworld – the presentation of Augustine in non-Augustinian texts

Anja Bettenworth

This article discusses texts from the European tradition and from the modern Maghreb in which Saint Augustine comes back from the afterlife. In these texts, the person of Augustine is used to convey important messages, which are not necessarily consistent with our knowledge of the historical Augustine. Instead, Augustine’s apparitions (as a narrator or a dialogue partner) are characterized by a mixture of familiarity and unfamiliar elements. In Petrarch’s dialogue Secretum meum, familiarity between Augustine and his interlocutor Franciscus is established through a shared knowledge of classical Latin texts, which are then employed to promote new, humanist views. In Abdelaziz Ferrah’s novel Moi, saint Augustin (Algiers, 2014), on the other hand, the European view of Augustine is rejected. Augustine is not presented as the Church father, but as a North African berber. Familiarity with his African readers is established through allusions to African customs, monuments and landscape. This technique helps to reappropriate the figure of Saint Augustine in the postcolonial Maghreb.

1[Author’s note1]

2Even though Augustine is (apart from Cicero) the personality from antiquity we know best, over the centuries there have been many attempts to retell his biography and to fill the extant testimonies with new life. Some of these texts are not only concerned with Augustine’s biography, but also address his afterlife by describing miraculous apparitions of the saint or by presenting him as a teacher of timeless philosophical truths or even as a first person narrator who looks back on his own biography from a timeless vantage point. The latter version of Augustine’s afterlife is found, for example, in Abdelaziz Ferrah’s novel Moi, saint Augustin (published in Algiers in 2004). Comparing the peculiar narrative frame of this novel to other texts that feature post mortem apparitions of Augustine will help us better understand how the church father’s role functions in the modern Maghreb.

3The earliest vita Augustini, written in late antiquity by his disciple Possidius, bishop of Calama in North Africa, is a vivid example of how already Augustine’s contemporaries tried to preserve and transmit his legacy. This early biography is not very interested in miracles and apparitions (preferring instead to emphasize the edifying effect of Augustine’s prolific writings2), but medieval lives of the saint, like Jacob de Voragine’s Legenda Aurea, sometimes include apparitions of Saint Augustine after his death. In one episode in the Legenda Aurea, a miller is cured from ulcers on his shin by a vision of Saint Augustine3. In another, a monk is said to have seen Augustine in a vision as he was seated in his episcopal ornate on a radiant cloud4. Saint Bernard is reported to have had a vision of Saint Augustine during the matutine prayers5, and a Burgundian monk named Hugo, who had venerated the bishop of Hippo throughout his life, is escorted to heaven by Augustine and his canonicals6. These stories dwell on Augustine’s miraculous connection to the divine and mark him as a powerful saint and patron for the medieval Christian reader. They also serve to promote the veneration of Augustine, whose remains are enshrined in the North Italian city of Pavia7.

4Modern reworkings of Augustine’s life tend to focus on the saint’s human side. Several recent novels, both from Europe and from the Maghreb, focalize through the perspective of historical characters mentioned only briefly in Augustine’s own writings. Notably his anonymous partner of 15 years, who was clearly an important person in his life but is mentioned by him only in passing8, has gained the attention of Maghrebian and European writers alike9. This view from the periphery exonerates modern writers from having to delve too deeply into the tortuous and often intimidating legacy of the church father – no easy material even for specialists – while at the same time, it opens up the possibility of creatively rewriting his biography and gaining a fresh look at his personality.

5In contrast, scenarios in which Augustine returns from the dead focus all the attention on Augustine himself, investing him with a special form of authority that regular human narrators do not have. This perspective is also interesting because, as we shall see, it situates the texts in a long tradition of similar scenes in world literature and therefore offers ample avenues of comparison. It also opens up questions of authority and reliability which are especially important for historical novels from the modern Maghreb.

6Generally speaking, literary underworld scenes can be divided into three major categories:

71. Scenes in which a living person enters the underworld to fulfill a specific task or obtain specific information (e.g., Hercules capturing Cerberus, Aeneas asking his deceased father for help);

82. Scenes in which a person (living or on the verge of death) has a vision of the underworld, sometimes with wider implications for his or her view of the world (Aeneas seeing the various sections of the underworld, Dante wandering the Inferno, Purgatory, and Heaven in the Divina Commedia);

93. Scenes in which two or more people, at least one of them dead, discuss various matters, not necessarily related to the underworld (Petrarch discussing with Saint Augustine in his work De secreto mearum curarum)

10Closely related to these scenes is a literary technique in which a deceased person narrates the story to the reader. In this case, the frame of the novel, rather than a single scene, is set in the netherworld. Features of the three types of literary underworld scenes may be combined: for example, Aeneas asks his deceased father for help (i. e. he requires specific information), but also gains a vision of the layout of the underworld).

11All of these scenes portray the underworld as a powerful and meaningful place that surpasses normal human experience. Except for the specific scenario in which a hero like Hercules or Orpheus descends into the underworld to fulfill a task such as capturing Cerberus or bringing back Eurydice, the idea that superior knowledge can be gained from contact with the deceased is dominant in these scenes. Inhabitants of the underworld know more than the living and can share their superior wisdom if they wish to do so. For this reason, underworld scenes are closely related to visions in which a deceased appears to a living person either in sleep or in a sort of rapture or to scenes of necromancy, in which the deceased is forced to speak to the living. While the goal of transmitting superior knowledge and guidance is often the same in both scenarios, underworld scenes are distinct from visions in that the protagonist enters and leaves the underworld alive, while in a vision or in necromancy, the deceased comes back to earth.

12The idea that deceased persons may be seen by the living and even communicate with them is a staple beginning in ancient texts. In addition to underworld scenes, there are ghost stories told at the dinner table for entertainment10, as well as also serious discussions of strange encounters and experiences that the narrator tries to understand. In his letters, Pliny the younger relates two ghost stories and combines them with the experience of a young politician (which he considers ‘true’). In this episode, a personification of Africa appears to the young man and foretells his magnificent career as a future governor of Africa proconsularis (Plin. ep. 7.27). The true significance of the vision is discovered only in hindsight, when the young politician has already achieved the post: at the moment of the supernatural encounter, however, the vision is not unambiguous11.

13For most of his life, the historical Augustine does not give much weight to such experiences12. There are no supernatural apparitions or miracles connected to his conversion13, and the young Augustine shows little interest in them. The only miracles and apparitions he accepts are those found in the First Testament and the gospels (de vera religione 25.47 and de utilitate credenda 17.35)14. In his own time, he rejects the idea of miracles, because they are no longer necessary in a world in which the Christian faith has already taken root. His attitude changes around 414/415, when the relics of Saint Stephen are being transferred to the North African city of Uzalis, where they are said to work miracles. Augustine now believes that miracles are still occurring in his own time, and in conf. 9.12, he talks about a miraculous “healing” from a toothache he experienced himself15. Around the same time (414/415 CE), Evodius, bishop of Uzalis, who had arranged for Saint Stephen’s miracles to be collected16, and who is a close companion and compatriot of Augustine from Thagaste (see conf. 9.17 and 9.31), asks Augustine’s opinion on the alleged apparitions of the deceased and on prodigious dreams (Aug. ep. 158). He quotes instances in which the deceased have been seen by several people entering and leaving houses and mentions a dream in which angels prepare for the arrival of a recently deceased young man from his monastery. His primary concern is understanding how these visions occur and whether they are trustworthy: i. e. if they convey superior knowledge about the fate of the deceased young man in the afterlife, for example. In his response (ep. 159), Augustine does not provide a conclusive answer. He notes that mental activity, either in dreams or while awake, is a normal human experience, even though humans are at a loss to explain what causes these mental images and how exactly they work. If these normal processes of the mind are inexplicable, how much more so the rare perceptions of the deceased who seem to convey superhuman knowledge17. While Augustine in this letter seems to group visions of the deceased under the workings of the mind, in his work on prophecies of demons he attributes their ‘prophecies’ to their extraordinarily long life. Because demons have been around for centuries and have extremely perceptive senses, they possess a superior knowledge on the causes of things and their hidden interconnections18. This advantage enables them to make well-founded assumptions about the future, which are then, from humans’ limited perspective, perceived as prophecies. In both cases, Augustine seems to prefer a logical, if sometimes hidden, explanation for the knowledge that is being conveyed, even if he does not rule out the possibility that supernatural apparitions are possible19. He also has a nuanced attitude on the different forms of ‘miracles’ and their role in God’s plan20.

14Augustine’s view is very different from the miracles, prophecies and encounters with the underworld enshrined in classical Latin literature, especially in Vergil’s Aeneid, Rome’s national epic since the Augustan period. Even though Roman readers, at least in Late antiquity, do not necessarily take the story of the Aeneid at face value21, it still remains a powerful reference point, as it encodes important elements of traditional Roman identity. For this reason, the prophecies in the Aeneid become the target of Augustine’s critique, especially in De civitate Dei, in which he tries to defend the Christians against the accusation that they caused Rome’s downfall by abandoning traditional Roman values and religious rites. He points out that the prophecies in the Aeneid, meaningful as they are for a Roman audience, are no prophecies at all because Vergil invented them after the event and projected his own view of Rome’s place in the world into the past and into the sphere of the divine22. In reality, these predictions are not supported by any divine authority23.

15For traditional pagan Romans, the fact that Vergil wrote the Aeneid in Augustan times and looked back into a mythical past is of course no objection against an inherent truth expressed in Vergil’s poem. Poets are presented as divinely inspired, and the constant presence of Gods and divine prophecies assures the reader that the message conveyed by the Aeneid is supported by the world order of which the gods are representatives. Early on, the reader knows that Aeneas will reach his final destination, that he will found the city that is the predecessor to Rome and that he embodies virtues that they can recognize as their own. Familiarity, rather than fear or estrangement, dominates the atmosphere in the Aeneid.

16The same atmosphere of familiarity is pervasive in one of the most famous literary texts in which it is not a supernatural being, but Augustine himself who intervenes from the underworld to lend guidance to a hapless mortal. In Francesco Petrarch’s dialogue De secreto conflictu curarum mearum, a personification of Veritas (“Truth”) appears to the writer and helps him answer his philosophical and literary questions. She does this by introducing Augustine to him who, she says, is the most apt interlocutor, because Franciscus has always loved him and being loved by one’s students enhances success in teaching. It is telling that Petrarch immediately recognizes Augustine, even before Veritas reveals his identity: The combination of his African dress and his Roman eloquence makes it clear that the stranger must be the bishop of Hippo. The church father then enters into a philosophical dialogue with Franciscus. While Augustine’s opinions in this dialogue are sometimes distinctly un-Augustinian and therefore puzzling to a reader who is familiar with Augustine’s writings24, the setting and the way the dialogue is framed suggest an atmosphere of deep familiarity between the Italian Humanist and his North African interlocutor: Right at the beginning of the dialogue, the speaker greets the fair virgin whose identity he does not yet know with the words Aeneas directs at his mother Venus when she appears to him in human disguise at the shores of Carthage (Verg. Aen. 1. 327-328: o quam te memorem, uirgo ? namque haud tibi uultus / mortalis). But while Venus keeps her true identity a secret, Veritas reveals to the astonished Franciscus her name. He is thus more fortunate than his model Aeneas. At the same time, the interaction between the two suggests that classical ancient texts are a valid tool for interpreting the experiences of the present25.

17At the same time, the idea of a woman who is in some way connected to the supernatural world and who introduces a seeker to a male authority who subsequently sheds light on some of his most important questions is borrowed from Vergil’s Aeneid: In book 6, Aeneas is led into the underworld by the Sibyl of Cumae and reunited with his father Anchises who then reveals to him important aspects of the future and his own destiny26. Given that the persona of Franciscus is introduced as an avid reader of Saint Augustine’s works, he is probably also familiar with Augustine’s famous reaction to the prophecies in the Aeneid: These ‘prophecies’ are not valid because they are given by Vergil only in hindsight, and they are uttered by gods who are no more than demons27. The Franciscus of the Secretum is thus moving in a context which is heavily indebted to literary models and therefore has a familiar ring to Petrarch’s persona as well as to the reader, who is supposed to read a Latin treatise and therefor be steeped in the tradition of Latin literature28.

18The fact that the dialogue is not in Italian but in Latin, the language of philosophy and higher education, also means that it is written in a language shared by the historical Petrarch and the historical Augustine. Supervised by Truth herself, their literary personae immerse in a conversation that is marked by trust and respect. They built their argumentation on a shared familiarity with Latin literature. When Augustinus quotes from the Aeneid to strengthen his argument that tears of sorrow or remorse are in vain if there is no change in one’s mindset, he insists that of many possible examples he just chose one, because it is “a household example” (domesticum exemplum), i. e. well known to his interlocutor Secretum 1.14:

Aug. Hoc inceperam, atque hoc prosequor : contigisse tibi hactenus quod multis, quibus dici potest versus ille Vergilii : ‘mens immota manet, lacrimae volvuntur inanes’. Verum ego, etsi multa congerere poteram, unico tamen eoque domestico exemplo contentus fui.

19Shortly afterwards, he tells Franciscus that he has not made a sufficient effort to liberate himself from his troubles, and that he should remember Ovid’s verse that wanting something is not enough, you must crave it in order to be successful. Franciscus acknowledges that he understands and accepts Ovid’s idea, and that he had thought his desire was strong enough by Ovid’s standards (Secretum 1.15: Aug. An non succurrit illud Ονidii : velle parum est ; cupias, ut re potiaris, oportet. Fr. Intelligo, sed et desiderasse putabam). Later in book 1, when Augustinus and Franciscus discuss the detrimental effect of worldly worries on the mind, Augustinus quotes a passage he has found “somewhere in Cicero”. Franciscus chimes in and correctly names the Tusculan Dialogues as its source29. Time and again, the reader is thus reminded that Augustine is not really teaching anything new to Franciscus, but is instead reminding him of helpful passages from his own engagement with the classics30. The argumentation thus runs along familiar lines in the tradition of philosophical debates that hark back all the way to antiquity: Boethius’ De consolatione philosophiae has long been recognized as one of the models for Petrarch’s work31, and the fact that he does not mention it while quoting from a host of ancient authors, has sparked a scholarly debate32. In the Consolatio, the personified Philosophia tries to console the imprisoned Boethius, she too admonishes him to remember and apply the philosophical teachings he has been studying since he was a young man. Medieval and early modern debates, an additional model for Petrarch’s dialogue, also evolve on the backdrop of a shared education and familiarity with all the relevant academic writings. Given these models, it is not surprising that Petrarch’s Augustine does not come back from the afterlife with a superior knowledge that transcends human capacities. Instead, he conducts the dialogue much the way an experienced philosopher would.

20The heavy reliance on ancient pagan texts, another feature Petrarch’s Secretum shares with Boethius’ Consolatio, is nevertheless surprising in the mouth of the church father Augustine. While the historical Augustine is of course imbued by classical erudition and has no qualms about showing it, his first point of reference is Scripture, and his argumentation is ultimately a theological one. While this background is not completely absent (in Secretum 1.13 Augustine refers to his conversion scene in the garden of Milan as described in his Confessions, and Franciscus acknowledges that he has read it33) it is not at the center of the learned debate in the Secretum. Researchers have long pointed out that by creating a setting that resembles traditional philosophical dialogues and then having his Augustine argue in a most un-Augustinian way, Petrarch cloaks his new, humanistic view on antiquity in a veil of superficial familiarity34. His access to the ancient world is not regulated by Fides (or any of the traditional personifications that serve as judges in a medieval disputatio), but by Veritas herself. It is Veritas who introduces Augustine and gives him credit, but in contrast to the typical endings of medieval debates, there is no final verdict35. Veritas remains silent, letting Augustine and Franciscus speak for themselves. The fact that Augustinus is brought back from the afterlife by Veritas underscores his authority, but it does not seem to entail any superhuman knowledge. His return from the dead is first of all a narratological strategy to bridge the time gap that separates him from his admirer Franciscus.

21In Maghrebian novels featuring Augustine, the church father also sometimes returns from the dead, but he is not the familiar Christian saint of the Legenda Aurea or the learned teacher of philosophy of Petrarch’s Secretum. In Abdelaziz Ferrah’s novel Moi, saint Augustin, published in 2004 in Algiers, ‘Augustin’ retells his biography from the afterlife. Having him speak from this vantage point invests him with an authority a normal human narrator cannot have. But just as in Petrarch’s Secretum, this special position does not seem to grant him access to the divine and its prophetic power: Unlike Anchises in the Aeneid, the Augustines of Petrarch and Ferrah do not reveal the future. There are notable differences between them, too: Unlike Petrarch’s Augustine, who is introduced by Veritas herself, in Ferrah’s novel he does not derive his special position from any authority, but simply from the fact he has been witnessing human history and the reception of his own life and works as it unfolded after his death in 430 CE. His superior knowledge thus often refers to historical facts that would normally be anachronistic for a person from antiquity: He compares the imperial Roman agentes in rebus to the Nazi Gestapo (Ferrah, 2004, 22836) and hesitantly likens his partner Tamelsa to Macchiavelli, pointing out, at the same time, that this an anachronism37. His longevity grants him knowledge, but unlike Anchises in Vergil’s Aeneid, there is no sign that he is aware of any divine plan for the world and his interlocutors. His role is therefore closer to the historical Augustine’s idea that the superhuman longevity that is characteristic for demons also grants them superhuman, yet limited knowledge38. But while the demons, in Augustinus’ view, use their historical knowledge to interpret the future and inflate their own importance, in Ferrah, Augustin employs his knowledge to interpret the past. His primary concern is the way in which the reception of his historical persona has unfolded in the Western world and the way it has idealized him in an unduly fashion. Most importantly, the way Europeans looked at him has obscured his local African roots. Ferrah’s Augustine is steeped in Berber tradition, and these traditions are more important to him than the honors he received from his European admirers. At the beginning of the novel, Augustine mentions his beatification by the Catholic Church and points out that it had never been his intention to become a saint39. Augustine’s reputation as a saint is first attributed to the will of an unspecific group of addressees (“vous”) but then tied closely to the Catholic Church which is explicitly called the Roman Church. Ferrah’s emphasis on “Rome” is striking because Augustine is held in high esteem by the Protestant Churches as well, both for dogmatic reasons and for the fact that Martin Luther was an Augustinian monk40. But it is the references to Roman traditions that have shaped the history of the modern Maghreb: French settlers justified the colonization of the Maghreb with their revival of ancient “Latin Africa” (“Afrique latine”) of which Saint Augustin was an important part. In his Life of Saint Augustin, French writer Louis Bertrand illustrated this concept41. Soon, it was merged with the idea that the Catholic traditions of France implied a special connection to that North African saint and that laying claims to his home region was a logical consequence of this connection42. The colonists’ view that Roman North Africa was part of the French/European cultural heritage casts its shadow also on the reception of antiquity in the newly independent states of Tunisia and Algeria. Autocrats like Ben Ali liked to point out the magnificent ancient sites of their countries which did not have to fear comparison with European Roman monuments, and Augustin appeared on Maghrebian coins and stamps. All these forms of reception explicitly or implicitly emphasized the fact that the Roman heritage of North Africa was similar to the Roman heritage of Europe (or even surpassing it in its splendor) and that the modern states of the Maghreb were therefore on equal terms with the former colonialists. By having his Augustin challenge the image that the “Roman” Catholic Church has helped shape of him, Ferrah points to a very different perception of the local Roman past: He is not stressing the traits that made Augustine a “European” saint, but creates an Augustin who is distinctly African and a Berber43. The differences start with the name (in the novel, Augustin says that his true name was Aurègh), extend to his native language (unlike the historical Augustine, Ferrah’s Augustin speaks an ancient form of Tamazigh and learns Latin only in school44) and also affect the way he counts the years (the Berber spring festival of tafsout is mentioned several times45). While Petrarch creates a world in which Augustinus and his dialogue partner Franciscus argue over philosophical questions but never about the rules of their conversation, Ferrah’s Augustin alienates the reader by questioning basic assumptions about his person. While Petrarch’s characters comment on the basis of a shared knowledge of literary history, Ferrah’s Augustin often lectures his addressee (and the reader) about North African history and literature (see e. g. Ferrah, p. 44-52 and 176-178). He comes back from the afterlife not to remind them of what they know, but of what they do not know. Interestingly, though, just as Petrarch cloaks his Augustinus’ un-Augustinian theories in a veil of superficial familiarity, Ferrah hides familiar details under the surface of a seemingly alienated past The reader may not know much about ancient history, the reader may hold false assumptions about Augustin as transmitted by the European tradition, but as long as the reader is a Berber, the unfamiliar Augustin who emerges in Ferrah’s novel shares many traits with him. The name Aurègh resonates with local onomastic traditions, the fact that Ferrah’s Augustine learns Latin in school mirrors the experience of Berber children who learn French in the as a foreign language in a school system shaped by colonial traditions46. Augustine leaving for Europe to find better working conditions may also resonate with a local reader. Many other details in the novel reinforce this sense of familiarity amidst the unfamiliar. The landscape of Africa plays a big role in the imagination of Ferrah’s Augustin, monuments and sites from modern Tunisia and Algeria form the backdrop of the novel’s action47, and local Berber costumes are practiced by the novel’s characters48.

22A similar, yet more playful strategy is employed by Kebir Ammi in his novel Thagaste. The novel is set in 388 CE, at the moment of the return of the newly converted Augustine to his native village of Thagaste and consists of short monologues in which Augustine himself and several other personalities offer their view on Augustine’s homecoming. The political situation in the novel is tense, the Roman occupation bears down on the residents of Thagaste, and Augustine’s father would rather see Augustine fighting the Romans than living as a monk in his native land. From the individual statements it becomes clear that the various speakers not only know Augustine, but also each other: They are for the most part residents of Thagaste, bound together by their shared connection to the land and by a complicated interpersonal network and a shared history. Even though Augustin’s illustrious career outside the village and his surprise return make him stand out, he is still very much part of the fabric of this rural African community. While Petrarch creates a sense of belonging by the literary erudition shared by Augustinus and Franciscus, and Ferrah ties his Augustin/Aurègh to his native Africa by a shared local Berber experience, Ammi makes his Augustin an inextricable part of the network of local village gossip. He is seen and commented on by a plethora of local people and serves as a unifying theme that binds the various perspectives together. At the same time, all these comments are marked as strictly subjective. Each chapter in the book bears the name of an individual (some of them fictitious, some historically attested, like Augustine’s father Patricius and Augustine’s friend Nebridius49). Among them is a certain (fictitious) Rabbi Akiba, who plays a special role in that he comes back from the afterlife to comment on what he sees in Thagaste50. He is a playful character, a regular customer in the taverns of the afterlife, and he stands out by his irreverent remarks. In this case, the speaker does not hold the authority that is usually granted to persons who come back from the afterlife to share a message. His perspective is no more reliable than that of the other characters (and maybe even less so given that he is a drunkard). But Akiba’s presence in the novel is still important because he creates a link to past generations and, by coming back from the deceased, a link between Augustine’s timely existence and the realm of eternity. The rigorously individualized views we get of Augustine in the novel are more than a glimpse into a fragmented history. No single perspective, including that of Akiba, may be perfect, but they all capture some aspect of an outstanding individual whose importance is not limited to his own time51. Familiarity is achieved through the ordinary behavior of the people who inhabit the novel, none of whom, not even the ghosts of the deceased, wield ultimate interpretative power.

23Stories about Saint Augustine returning from the afterlife have a long and fascinating history. They go back, if not to his first biographer Possidius, at least to the sources auf Jacob de Voragine’s Legenda Aurea. The apparitions invest Augustine with a certain authority, but they are constructed in a very different way. In the Legenda Aurea, visions of Augustine bring healing to the sick, comfort the dying, or convey important aspects of the church father’s character. The addressees of the visions recognize Augustine even when there are no outer characteristics to identify him, and when there is no direct communication. Familiarity is created through the veneration of the saint and the common bond created by the Christian faith. Traditions of what to expect from a typical patron saint probably also play a part, while Augustine’s own nuanced attitude towards apparitions and miracles is not discussed. In Petrarch’s Secretum, on the other hand, Augustine is first recognized by Franciscus by his African dress and his eloquence, details he could have deduced from Augustine’s writings, and familiarity is then created by a shared mastery of classical, mostly pagan texts and of the rules of philosophical debates. This familiarity overrides the fact that the content of the dialogue is more humanistic than truly Augustinian, and it works because the ideal reader of the Secretum shares the erudition of its characters. Magrebian authors, in the tradition of César Benattar’s Cinéma aux enfers (1927), also have Augustine occasionally come back from the afterlife. In Abdelaziz Ferrah’s novel Moi, saint Augustin, Augustin/Aurègh recounts his biography up to his conversion from the afterlife.

24But while Augustine’s superior knowledge is, in Petrarch, embedded in an atmosphere of familiarity, in the Maghrebian novel the vantage point of a narration from the afterlife is used to create a sense of distance. Ferrah’s Augustine reminds his readers that the church made him a saint, but that was not what he intended to be, nor is it everything he was. He then goes on to recount his other, African and Berber self, which has gone unrecognized for centuries, even though Augustine remains one of the most famous authors worldwide. The apparition from the afterlife that marks Augustine as a distant figure in Ferrah’s novel also opens up new possibilities: the sense of unfamiliarity leaves room to discover him from a fresh and distinctly non-European perspective.

1 I thank India Watkins Nattermann for polishing the English of this article. All remaining errors are entirely mine.

2 See Anja Bettenworth, “Literarisches Schaffen als imitatio Christi in der Augustinusvita des Possidius”, Anja Bettenworth, Dietrich Boschung, Marco Formisano (eds), For Example. Martyrdom and Imitation in Early Christian Texts and Art, Paderborn, Wilhelm Fink, 2020, p. 193-214 (= Morphomata 43). A new translation and commentary of Possidius’ vita Augustini is provided by Kuhn (JbAC Ergänzungsband), forthcoming in 2023.

3 Legenda Aurea 124.2, p. 562: Molendinarius quidam in beatum Augustinum specialem devotionem habens cum quandam infirmitatem, quae dicitur phlegma salsum, in tibia pateretur, beatum Augustinum devote in sui adjutorium invocabat. Cui per visum sanctus Augustinus apparuit et tibiam manu palpans integrae restituit sanitati.

4 Legenda Aurea 124.4, p. 562: In monasterio, quod Elemosina dicitur, monachus quidam in vigilia sancti Augustini raptus in spiritu vidit nubem splendidam coelitus delapsam et super nubem Augustinum sedentem pontificalibus insignitum.

5 Legenda Aurea 124.4, p. 562: Sanctus quoque Bernardus dum quadam vice in matutinis exsistens aliquantulum obdormivisset et de quodam tractatu Augustini lectiones legerentur, vidit quendam pulcherrimum juvenem ibi stantem, de cujus ore tantus inundantium aquarum impetus exibat, quod totam illam ecclesiam videretur replere. Qui Augustinum esse non dubitavit, qui fonte doctrinae totam ecclesiam irrigavit.

6 Legenda Aurea 124.6, p. 563: Apud Burgundiam in monasterio, quod dicitur Fontanetum, erat quidam monachus, Hugo nomine, sancto Augustino valde devotus […], quem etiam crebra supplicatione rogaverat, ut ipsum ex hac luce migrare non sineret, nisi in die suae sacratissimae sollemnitatis. Ipse igitur XV. die ante festum eiusdem sic coepit duris febribus aestuare, ut in vigilia ipsius super humum tamquam moriens poneretur. Et ecce plures decori ac fulgentes viri amicti albis ecclesiam dicti monasterii processionaliter intraverunt, quos sequebatur quidam reverendus pontificalibus insignitus. Quidam autem monachus in ecclesia consistens hoc videns obstupuit et, quinam essent vel quo pergerent, inquisivit. Cui unus eorum dixit, quod sanctus Augustinus esset cum suis canonicis, qui ad devotum suum morientem pergeret, ut eius animam ad regnum gloriae deportaret.

7 The stories about posthumous apparitions and miracles of Saint Augustine related in the Legenda Aurea seem to be based on local traditions from Northern Italy, see Edmund Colledge, “James of Voragine’s ‘Legenda sancti Augustini’ and its Sources”, Augustiniana 35, 1985, p. 281-314.

8 The anonymous woman is the mother of Augustine’s son Adeodatus (conf. 4.2), she separated (or was separated) from him when a promising option for marriage arose for him in Milan (conf. 6.15.25). Augustine describes the separation in searing terms (conf. 6.15.25). He also mentions her briefly in De bono coniugali 5.5.

9 Novels that explore the perspective of Augustine’s partner include, among others, Claude Pujade-Renaud, Dans l’ombre de la lumière, Arles, Actes Sud, 2013; Jostein Gaarder, Vita brevis, Oslo, Aschehoug, 1996; Pierre Villemain, Les Confessions de Numida, l’Innommée de Saint Augustin, Paris, Éditions de Paris, 1957, but also Abdelaziz Ferrah’s novel Moi, saint Augustin, Algiers, Apic Alger, 2004, which dedicates ample space to this unnamed woman.

10 On the narrative function of such ghost stories in Petronius’ Satyrica see Stavros A. Frangoulidis, “Trimalchio as narrator and stage director in the ‘Cena’: an unobserved parallelism in Petronius’ Satyricon 78”, CPh 103, 2008, p. 81-87.

11 On ghost stories in Pliny, see Yelena Baraz, “Pliny's epistolary dreams and the ghost of Domitian”, TAPA 142, 2012, p. 105-132.

12 He seems to become more open to the possibility of miracles and miraculous healings at the end of his work on De civitate Dei, where he compiles a long list of miraculous events, some of them from his immediate surroundings in North Africa (Aug. civ. 22.8).

13 The famous conversion scene in the garden of Milan in conf. includes of course a child’s voice chanting tolle, lege, and the context insinuates that the voice is a hint from God who inspires Augustine to pick up the letters of the apostle Paul. But in his other writings, Augustine also gives different accounts of his conversion in which there is nothing miraculous about it. In these accounts, the sermons of bishop Ambrose of Milan and health issues play a significant role (cf. the prologue to De vita beata and De utilitate credenda 20 and short remarks in Acad. 2.3-4; c. ep. Man. 3 and duab. An. 1.11). When these sources are taken together, it becomes apparent that Augustine considers his conversion, just as all of his life guided by God, without giving too much emphasis on supernatural phenomena. The bibliography on the conversion is endless. Courcelle’s study is still important (Pierre Courcelle, Recherches sur les Confessions de Saint Augustin, Paris, Boccard, 1968), for newer contributions see Stefan Freund, “Bekehrungsorte. Rom und Mailand in Topographie und Topik von Konversionsschilderungen”, Therese Fuhrer (ed), Rom und Mailand in der Spätantike, Repräsentationen städtischer Räume in Literatur, Architektur und Kunst, Berlin, Boston, De Gruyter, 2012, p. 327-341, and Kathrin Susan Ahlschweig‚ “Tolle lege: Augustins Bekehrungserlebnis (conf. 8.12.29)”, Andreas Haltenhoff (ed), Hortus litterarum antiquarum: Festschrift für Hans Armin Gärtner zum 70. Geburtstag, Heidelberg, Winter, 2000, p. 19-30 (= Bibliothek der klassischen Altertumswissenschaften. Reihe 2. 109).

14 Cp. also Aug. Io ev. Tr. 24.1: miracula, quae fecit dominus noster Iesus Christus, sunt quidem divina opera, et ad intelligendum Deum de visibilibus admonent humanam mentem. (“The miracles worked by our Lord Jesus Christ are divine workings, and they admonish the human mind to infer God from visible things.”).

15 Conf. 9.12: dolore dentium tunc excruciabas me, et cum in tantum ingravesceret, ut non valerem loqui, ascendit in cor meum admonere omnes meos, qui aderant, ut deprecarentur te pro me, deum salutis omnimodae. Et scripsi hoc in cera et dedi, ut eis legeretur. Mox ut genua supplici affectu fiximus, fugit dolor ille. sed quis dolor ? aut quomodo fugit ? expavi, fateor, domine meus deus meus, nihil enim tale ab ineunte aetate expertus fueram, et insinuati sunt mihi in profundo nutus tui. (“Thou at that time tortured me with toothache; and when it had become so exceeding great that I was not able to speak, it came into my heart to urge all my friends who were present to pray for me to You, the God of all manner of health. And I wrote it down on wax, and gave it to them to read. Presently, as with submissive desire we bowed our knees, that pain departed. But what pain? Or how did it depart? I confess to being much afraid, my Lord my God, seeing that from my earliest years I had not experienced such pain. And Your purposes were profoundly impressed upon me.”).

16 Evodius builds a memoria for the protomartyr Stephen in Uzalis. The collection of Saint Stephen’s miracles (De miraculis S. Stephani protomartyris) that he supervised seems to hark back to civ. 22.8-10, see Wolfgang Hübner, Augustinuslexikon 2, Basel, Schwabe, 1996-2002, p. 1158-1161 s.v. Euodius). He also has the miracles of one Petronia recorded and publicly recited, civ. 22.8.

17 Aug. ep. 159.5: Et vigilat homo, et dormit homo quotidie, et cogitat homo : dicat unde fiant ista similia formis, similia qualitatibus, similia motibus corporum, nec tamen materie corporali ; dicat si potest. Si autem non potest, quid se praecipitat de rarissimis aut inexpertis quasi definitam ferre sententiam, cum continua et quotidiana non solvat ? For the same topic cp. Aug. Gn. litt. 12 which he was writing at the time of his answer to Evodius and to which he refers his fellow bishop, cp. Matthew Drever, “De Genesi ad litteram 12: Paul and the Vision of God”, Johannes Brachtendorf, Volker Drecoll (eds), Augustinus De Genesi ad litteram. Ein kooperativer Kommentar, Paderborn, Brill, 2021 (= Augustinus, Werk und Wirkung 13), p. 313-328.

18 De divinatione daemonum 7. A similar thought is found in Gn. litt. 2.17. (37) (28/1. 61.19-22): quibus [sc. daemonibus] quaedam uera de temporalibus rebus nosse permittitur partim subtilioris sensus acumine, quia corporibus subtilioribus uigent, partim experientia callidiore propter tam magnam longitudinem uitae.

19 That inexplicable apparitions and prophecies may originate either from God and his angels or from demons poses a general difficulty: how can a human be sure about the source and nature of these experiences? Augustine deals with this question in, for example, div. qu. 79.4.

20 For miracles (miracula) Augustine distinguishes between three categories (cp. Jean-Michel Roessli, Augustinuslexikon 4, Basel, Schwabe, 2012-2018, p. 25-29 s.v. mirabilia, miraculum): a) a phenomenon in the physical world, which unfolds contra naturae usitatum cursum (Gn. litt. 6.14.25). It is not against nature, but merely an unusual manifestation of nature’s course that arouses wonder in the human observer. b) a phenomenon that causes the spectator to wonder (mirari): miraculum voco quicquid arduum aut insolitum supra spem vel facultatem mirantis apparet (util. cred. 34). The miracle is subjective: it is not unusual in an absolute sense, but it defies the spectator’s expectations (e.g., Aug. util. cred. 34: miraculum voco quicquid arduum aut insolitum supra spem vel facultatem mirantis apparet. (“I call a miracle everything that is hard to understand or above the expectation or the mental capacity of the person who marvels at it”). c) a phenomenon that has theological meaning because it is a sign from God: miracula, quae fecit dominus noster Iesus Christus, sunt quidem divina opera, et ad intelligendum Deum de visibilibus admonent humanam mentem (Io ev. Tr. 24.1) In De civitate Dei 21.8, Augustine mentions four forms of miracles (monstra, ostenta, portenta, prodigia), which all “show” or “predict” something to the human spectator. Their differentiation is based on the (presumed) etymology of the words.

21 See e.g. Macr. Sat. 5.17.5 (about Vergil’s version of the Dido-myth): quod ita elegantius auctore digessit, ut fabula lascivientis Didonis, quam falsam novit universitas, per tot tamen saecula speciem veritatis obtineat et ita pro vero per ora omnium volitet, ut pictores fictoresque et qui figmentis liciorum contextas imitantur effigies, hac materia vel maxime in effigiandis simulacris tamquam unico argumento decoris utantur, nec minus histrionum perpetuis et gestibus et cantibus celebretur and Augustine’s own assessment in his confessions, Aug. conf. 1.13.22: non clament adversus me venditores grammaticae uel emptores, quia, si proponam eis interrogans, utrum verum sit quod Aenean aliquando Carthaginem venisse poeta dicit, indoctiores nescire se respondebunt, doctiores autem etiam negabunt verum esse.

22 Aug. civ. 5.12 (about Iupiter’s prophecy in the Aeneid): Quae quidem Vergilius lovem inducens tamquam futura praedicentem ipse iam facta recolebat cernebatque praesentia; verum propterea commemorare illa volui, ut ostenderem dominationem post libertatem sic habuisse Romanos, ut in eorum magnis laudibus poneretur.

23 The same criticism of the Aeneid’s prophecies is found in Aug serm. 105.10, PL 38 (1841), 622/623 (a sermon on Luc. 21.33): qui hoc terrenis regnis promiserunt, non veritate ducti sunt, sed adulatione mentiti sunt. poeta illorum quidam induxit Iovem loquentem, et ait de Romanis, ‘His ego nec metas rerum, nec tempora pono : / Imperium sine fine dedi’. non plane ita respondet veritas. Regnum hoc, quod sine fine dedisti, o qui nihil dedisti, in terra est, an in coelo ? Utique in terra. Et si esset in coelo, Coelum et terra transient. Transient quæ fecit ipse deus ; quanto citius quod condidit Romulus ? Later in the sermon, Augustine defends Vergil by pointing out that the false prophecy was made by Jupiter and not by the persona of the poet. According to Augustine, Vergil included this promise of eternity into the Aeneid to please his Roman readers even though he had said in georg. 2.498 that the Roman empire was transient. On the interpunction of the passage and its interpretation by Petrarch see Wolfgang Hübner, “Eine Vergil-Interpretation Augustins bei Petrarch”, Wiener Studien 120, 2007, p. 247-256, cp. also below fn. .

24 See e.g. Klaus Heitmann, ‘Augustins Lehre in Petrarcas Secretum’, Bibliothèque d’Humanisme et Renaissance 22, 1960, p. 34-53. He stresses that the whole of Augustinian thought is practically glossed over in this dialogue that sees Augustine as a speaker, cp. Carol E. Quillen, “A Tradition Invented: Petrarch, Augustine, and the Language of Humanism”, Journal of the History of Ideas 53, 1992, p. 179-207 and E. F. Cranz, “Some Petrarchan Paradoxes”, Reorientations of western Thought from Antiquity to the Renaissance, ed. N. Struever, Aldershot, Ashgate, 2006, p. 1-21.

25 For the Aeneid as a model of Petrarch’s Secretum, see Francisco Ciabattoni, “Il mito di Enea nel Secretum: naufragio sull’umanesimo”, Filologia e critica 31, 2006, p. 75-87. On the similarities between Venus in Aeneid 1 and Petrarch’s Veritas see ibid., p. 77-78. Veritas also plays an important role in Aug. sermo 105.10 on Luc. 31.33 (quoted above fn. ). Wolfgang Hübner, “Vergil-Interpretation”, art. cit., convincingly argues that there is a direct speech by Veritas in this sermon from which Petrarch quotes in a letter in his Liber sine nomine (ep. 4). This letter to the people of Rome was composed in 1352 (i.e. roughly at the time when Petrarch was working on the Secretum), on behalf of the Roman tribune Cola di Rienzo who was at the time a prisoner in Avignon. It is not entirely clear from the quotation if Petrarch noticed Augustine’s personification of Veritas, but there are indications that he did.

26 In analyzing Augustinus’ stance towards the love for Laura in Secr. 3.150, p. 220, Ciabattoni, art. cit., p. 86 points out an allusion to Aen. 6.540-543, but does not mention Aeneas’ encounter with Anchises.

27 Aug. civ. 5.12: velut loquente Jove […] poeta dicit : ‘Quin aspera Juno, / Quae mare nunc terrasque metu caelumque fatigat, / Consilia in melius referet mecumque fovebit / Romanos rerum dominos gentemque togatam. / Sic placitum. Veniet lustris labentibus aetas, / Cum domus Assaraci Phthiam clarasque Mycenas / Servitio premet ac victis dominabitur Argis.’ Quae quidem Vergilius Jovem inducens tamquam futura praedicentem ipse iam facta recolebat cernebatque praesentia.

28 For the role of the reader in the Secretum see Zs. Kiséry, “Das Thematisieren des Lesens. Zum Secretum von Petrarca”, Acta Classica Universitatis Scientiarum Debreceniensis 34-35, 1998-1999, p. 61-66. The underworld scene of the Aeneid enjoyed a rich afterlife in the European tradition. For its interpretation in the Middle Ages see Petra Korte, Die antike Unterwelt im christlichen Mittelalter: Kommentierung – Dichtung – philosophischer Diskurs, Frankfurt, Lang, 2012.

29 Secretum 1.37: Aug. Cicero siquidem in quodam loco, iam tunc errores temporum perosus, sic ait : “Nichil animo videre poterant, ad oculos omnia referebant; magni autem est ingenii revocare mentem a sensibus et cogitationem a consuetudine abducere”. Haec ille. Ego autem hoc velut fundamentum nactus, desuper id quod tibi placuisse dicis opus extruxi. F : Teneo locum : in Tusculano est. The quotation is taken from Cic. Tusc. 1.38.

30 Cp. also Kiséry, art. cit., p. 62: “Der Dialog ist im Grunde genommen ein ständiges Evozieren des ‘Textes’ der Vergangenheit, ein ständiges Hinweisen auf das schon Gelesene.” For more examples of this technique in the Secretum see ibid., p. 61-62.

31 Apart from the Consolatio, Augustine’s Soliloquia (in which a personified ratio servers as his interlocutor) have been identified as a model, as well as the Aeneid, see Ciabattoni, art. cit.

32 E. Loos, “Petrarca und Boethius. Das Verschweigen der ‘Consolatio Philosophiae’ im ‘Secretum’”, Klaus W. Hempfer (ed), Interpretation: das Paradigma der europäischen Renaissance-Literatur, Festschrift für Alfred Noyer-Weidner zum 60. Geburtstag, Wiesbaden, Steiner, 1983, p. 258-271 thinks that Petrarch omits Boethius because the Muses, the representatives of a poetry that was dear to him, are chased away at the beginning of the Consolatio. J. Küpper, “Das Schweigen der Veritas. Zur Kontingenz von Pluralisierungsprozessen in der Frührenaissance (Francesco Petrarca, Secretum)”, Poetica 23, 1991, p. 428-429 doubts this theory is correct because the Secretum is not concerned with poetry.

33 Aug. : miraque et felicissima celeritate transformatus sum in alterum Augustinum, cuius historiae seriem, ni fallor, ex Confessionibus meis nosti. Fr. : Νονi equidem, illiusque ficus salutiferae, cuius hoc sub umbra contigit miraculum, immemor esse non possum.

34 For Augustine as a symbol of humanism in Petrarch’s works see Christian Moser, Buchgestützte Subjektivität. Literarische Formen der Selbstsorge und der Selbsthermeneutik von Platon bis Montaigne, Tübingen, Niemeyer, 2006, p. 650-654.

35 The full title of Petrarca’s work, De secreto conflictu curarum mearum evokes the tradition of the medieval conflictus-literature. These debates, which often pitch allegories against each other, typically end with a consensus, sometimes by the verdict of a silent witness who serves as a judge, see Gerhard Regn and Bernhard Huss, Francesco Petrarca, Secretum meum, ed. and trans. G. R. and B. H., Mainz, Dieterich, 2004, p. 509-510.

36 Even in scholarly debates, the agentes in rebus are sometimes, in an somehat exaggerated way, called the “secret service” of the Roman emperors. See Christopher Kelly, Ruling the later Roman Empire, Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 2004, p. 207.

37 Ferrah, op. cit., p. 212: “Tamelsa, un diable ? Un Machiavel avant l’heure et le personnage ?” Anachronisms generally play an important role in Ferrah’s constitution of modern Berber identity. A particularly important example is the (fictional) visit of Augustinus and his Companion to the city of Thugga (modern Dougga in Tunisia), ibid., p. 206-208. On this episode see Anja Bettenworth, “Literarisches Schaffen als imitatio Christi”, art. cit.

38 For Augustine’s demonology in comparison to other church fathers cp. Florian Wekenmann, Die Dämonen bei Augustinus und die antike Dämonologie, Paderborn, Schöningh, Brill, 2023.

39 Ferrah, op. cit., p. 19: “Je suis pour vous tous Augustin le saint, El-Κeddous, plus exactement Saint Augustin. Cela m’honore. Je le suis parce que vous l’avez voulu ; parce que l’Église catholique romaine l’a voulu et peut être aussi parce que je le mérite un peu pour avoir défendu la Vérité divine ; probablement jusqu’au sacrifice suprême s’il le fallait, tout comme cela est digne d’un Berbère authentique dans une situation similaire. À l’origine, c’est à dire à ma naissance ou plus exactement sept jours après, comme le voulait notre tradition, je n’avais pas été appelé Augustin mais Aur ou plus précisément Aurègh ou Aouragh. […] Aurègh a été déformé pour donner Aurélius que vous m’aviez attribué, et a tort, comme mon nom de famille.” In this view, the personal name is closely connected to the identity of the individual. A Berber must have a Berber name, and a ‘deformation’ of the name entails a deformation of his identity. Yet, we know of many cases in the Greek and Roman world, especially from Ptolemaic and Roman Egypt, in which a person went by a local and a Greek or Roman official name (not necessarily connected etymologically) and used them interchangeably. In the case of Augustine, nothing in his works points to a local variant of his personal name. But attempts to link his name closely to his character are found also in Europe, namely in the Jacob de Voragine’s Legenda Aurea, where a (wrong) etymology is used to show that his name refers to his work to increase the church, Legenda Aurea Aug. 124.548-549: Augustinus hoc nomen sortitus est vel propter excellentiam dignitatis vel propter fervorem dilectionis vel propter etymologiam nominis. […] Dicitur enim Augustinus ab augeo et astin, quod est civitas, et ana, quod est sursum. Inde Augustinus quasi augens supernam civitatem.

40 On the reception of Augustine in the Reformation see e.g. Arnoud. S. Q. Visser, Reading Augustine in the Reformation: The Flexibility of Intellectual Authority in Europe, 1500-1620, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2011 with further bibliography.

41 See Jutta Weiser, “Augustinus als Symbolfigur der Afrique latine bei Louis Bertrand”, RQ 115, 2020, p. 63-82.

42 For the colonial reception of Saint Augustin in the modern Algerian town of Annaba (the ancient Hippo Regius) see Saint Ardeleanu, “Hippo Regius – Buna – Bone: Ein Erinnerungsort im Spiegel der kolonialzeitlichen Augustinusrezeption”, RQ 115, 2020, p. 29-56 and Claudia Gronemann, “Rewriting antiquity: Saint Augustine as mnemonic figure in francophone texts of the Maghreb”, Études littéraires africaines, 49, 2020, p. 192-197.

43 The term “Berber” is used in this article because it corresponds to the French “berbère” used throughout Ferrah’s novel. In the Tamazigh language of the modern Maghreb, the term Imazighen (sg.: Amazigh) is also often used for the non-Arab indigenous population.

44 The same is true, in Ferrah, for Augustine’s mother Monnica. In the novel, the Monnica is a native of the town of Thibilis, not far from Thagaste, where the local goddess Mon / Monna is venerated. Monnica is designated by her family as a future priestess of the goddess, and learns Latin to be able to understand the Christian enemies of the pagan faith, Ferrah, op. cit., p. 32: “Dans sa situation de future prêtresse du temple de Monn, elle avait appris, mais sans plus, à lire le latin à l’effet de se préparer à ne rien ignorer de tout ce qui pouvait se tramer dans les camps adverses ; notamment celui des Chrétiens surtout lorsqu’ils étaient portés par des Berbères maximalistes.” The plans of the family do not materialize because Monnica reads the letters of Paul and becomes a Christian, thus anticipating Augustine’s own way of conversion. While the name of the historical Monnica probably derives from the goddess Mon / Monna attested in Thibilis (CIL 8.14911 and 8.17798, cp. Serge Lancel, Saint Augustin, Paris, Fayard, 1999, p. 1056), and while it has sometimes been suggested, without much evidence, that Monnica was a Donatist before she and her family were converted to Christianity by Macarius, there is no hint that she ever was a pagan. W. H. C. Frend, The Donatist Church, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1952, p. 184 assumes that at least some family members of Monnica were Donatist.

45 In some Maghrebian novels, Augustine’s Berber identity is stressed by scenes in which famous personalities such as the Kahina visit his grave (Raouf Oufkir, Kahena, la reine guerrière. L’Impératrice des songes, Paris, Flammarion, 2010), or in which Augustine pays homage to the tomb of Berber kings (Ferrah, op. cit.). While these novels refrain from resuscitating a historical person from the dead, the importance of the graves still implies that there is an unbroken line of Berber heritage that is in itself timeless and includes Augustine along with other famous characters such as Massinissa and the Kahina. On the special form of remembering Augustine in the novels of Kebir Ammi see Bernadette Cailler, Carthage ou la flamme du brasier, Amsterdam, New York, 2007, Rodopi, p. 109-131.

46 Ferrah himself makes the comparison in the epilogue of his novel, Ferrah, op. cit., p. 350: “Ma génération, à la sortie de la deuxième guerre mondiale dans ces mêmes régions s’était trouvée dans une situation similaire avec le choc de l’école française, enfin ouverte aux Indigènes ; une semblable soif de savoir. Ce fut pour Augustin une étape aussi essentielle que pour ceux qui ont eu la chance d’accéder à cette école française et de voir s’ouvrir des horizons insoupçonnés jusque là.” The historical Augustine was a native speaker of Latin, as can be inferred e. g. from conf. 1.23: Homerus peritus texere tales fabellas et dulcissime vanus est, mihi tamen amarus erat puero. Credo etiam graecis pueris Vergilius ita sit, eum sic discere coguntur ut ego illum. Augustine wonders why he hated Homer as a schoolboy. He concludes that the method of teaching was to blame and assumes that Greek boys would feel the same aversion towards Virgil, if they were forced to study him the way he was forced to study Homer. For the use of Greek in Augustine and in late antique North Africa see I. Hadot, “Erziehung und Bildung bei Augustin”, C. Mayer, K.-H. Chelius (eds), Internationales Symposium über den Stand der Augustinus-Forschung vom 12. bis 16. April 1987 im Schloß Rauischholzhausen der Justus-Liebig-Universität Gießen, Würzburg, Augustinus-Verlag, 1989 (= Cassiciacum 39/1, “Res et Signa” Gießener Augustinus-Studien, Band 1), p. 117-118.

47 See Anja Bettenworth, “Raumkonzepte und Antikenrezeption in Abdelaziz Ferrahs Roman Moi, saint Augustin”, RQ 115, 2020 p. 250-267. English version of this article, “Concepts of Space and Reception of Antiquity in Abdelaziz Ferrah’s Novel Moi, saint Augustin”, Salah Hannachi (ed), Pertinence de la pensée de saint Augustin aux défis du xxie siècle, Carthage, Académie tunisienne des sciences, des lettres et des arts Beït al-Hikma, Tunis, 2022, p. 45-70.

48 At one point, Tamelsa, Augustin’s partner, consults a Berber shaman, to ward off evil from her newborn child: Ferrah, op. cit., p. 172: “Elle me surprit même un jour, mais pas outre mesure je dois le reconnaître, lorsqu’ elle m’avoua qu’elle allait, accompagnée de Ghana, consulter une chaman l’Ineqiqi berbère afin de réunir les meilleures chances de survie de notre enfant.” The lips of the newborn Augustine are lined with salt for protection, Ferrah, op. cit., p. 34: “Ce devait être plutôt le sel qui m’avait été passé sur les lèvres dès mon insignifiant vagissement pour empêcher les mauvais esprits de me pénétrer” and 35f. where ‘Augustin’ describes more local rites for the newborn which are conducted by Berber women including his mother “sans que cela le gênât de me dessiner une petite croix sur le front.” The combination of the sign of the cross made over young children and the salt is also found in the confessions of the historical Augustine, Aug. conf. 1.11.17: ego adhuc puer […] signabar iam signo crucis eius, et condiebar eius sale iam inde ab utero matris meae. It is not clear if the ‘salt’ in this passage is to be understood metaphorically or literally. A combination of both meanings is possible.

49 The combination of different perspectives is also characteristic for Ammi’s novel Sur les pas de saint Augustin, published in 2001, two years after Thagaste, see Claudia Gronemann, “Literarische Erkundungen dies- und jenseits von Algerien: Der Heilige Augustinus als transkulturelle Erinnerungsfigur bei Kebir Ammi”, RQ 116.1-2, 2021, p. 14-30, here p. 22-23. While in Thagaste the location remains the same and only the narrators vary from chapter to chapter, Sur les pas has every chapter set in a different place, but with the same narrator (the ‘visitor’). In both novels, the person of Augustine binds the different perspectives together.

50 The rabbi Akiba of the novel is not to be mistaken for his famous namesake Rabbi Akiba ben Josef who died in 135 CE. The character in the novel is the uncle of one of Augustine’s friends, so must be roughly one generation older than Augustine, who was born in 354 CE. In one of the last chapters of the novel, Akiba introduces himself, Ammi, Thagaste, p. 124: “Je ne suis pas un fou, messieurs, mais Akiba. Augustin connaît fort bien mon neveu. Comme vous, du reste. Et Julia. Fouillez. N’ayez crainte. Cherchez dans vos lointains souvenirs. – Vous m’y trouverez dans une vieille malle secrète. Eh bien, oui, j’ai réussi à fausser compagnie à la mort et je suis descendu l’autre jour à Thagaste, cette ville que j’aime comme je n’ai jamais aimé nulle femme au monde.” (“I am not mad, gentlemen, but Akiba. Augustin knows my nephew very well. Like you, by the way. And Julia. Dig. Do not be afraid. Search in your old memories. You will find me there in an old secret suitcase. Well, yes, I have managed to leave Death in the lurch and I have descended to Thagaste, this town which I love as I have never loved a woman in the whole world.”)

51 The timelessness of Augustine’s legacy is also important in other Maghrebian novels, even when Augustine is not their main character. In an epilogue to Germaine Beauguitte’s novel on the Berber queen Kahéna (La Kahéna, reine des Aurès, Paris, Éditions des Auteurs, 1959, p. 153), Augustine makes a brief appearance when he welcomes the Kahina, his “eminent compatriot”, to the afterlife. The queen, who had tried in vain to force back the Arab conquest of North Africa, in turn greets Jeanne d’Arc as a kindred soul. In the novel, Augustine is a representative of past Roman glory, but at the same time an African who acknowledges the Berber population, see Noureddine Sabri: La Kahéna, Un mythe a l’image du Maghreb, Paris, L’Harmattan, 2013, p. 96.

Actes des IVe journées augustiniennes de Carthage (11-13 novembre 2022).

Textes réunis par Tony Gheeraert.

© Publications numériques du CÉRÉdI, « Actes de colloques et journées d’étude », n° 30, 2024

URL : https://publis-shs.univ-rouen.fr/ceredi/1609.html.

Quelques mots à propos de : Anja Bettenworth

University of Cologne