Sommaire

Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson hors frontières

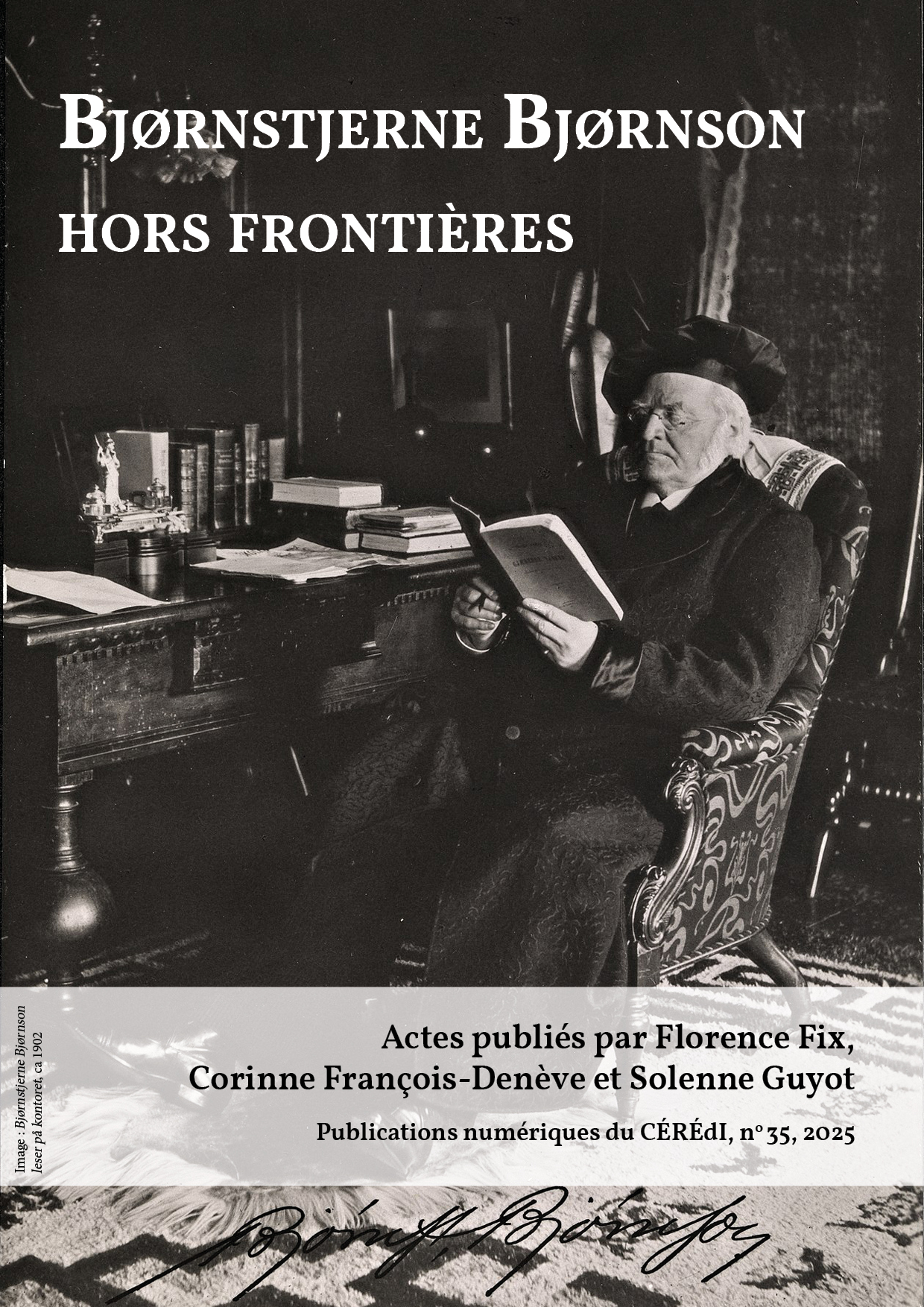

Actes de la journée d'études organisée à l'Université de Strasbourg en 2024, publiés par Florence Fix, Corinne François-Denève et Solenne Guyot

- Solenne Guyot Avant-propos

Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson, illustre méconnu du théâtre européen du xixe siècle - Corinne François-Denève et Solenne Guyot « Je retrouvais, dite par un homme, la question d’être une femme au monde. » Entretien avec Corinne François-Denève sur la (re)traduction d’En hanske [Le Gant]

- Annie Bourguignon Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson’s Maria Stuart i Skotland and Friedrich Schiller’s Maria Stuart

- Cécile Leblanc Wagnériser Bjørnson ? Hulda de César Franck et Charles Grandmougin

- Nicolas Diassinous Au-dessus des forces humaines au Théâtre de l’Œuvre : le Bjørnson de Lugné-Poe

- Miloš Mistrík Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson et la Slovaquie : la priorité est d’abord d’avoir un pays libre et indépendant, puis un théâtre national !

- Marthe Segrestin Leonarda et Nora, fausses jumelles

Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson hors frontières

Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson’s Maria Stuart i Skotland and Friedrich Schiller’s Maria Stuart

Annie Bourguignon

1When, in 1799, Friedrich Schiller began writing his tragedy Maria Stuart, it already existed more than 50 plays about the historical figure of Mary Stuart, Queen of Scots1. After that date, she kept inspiring dramatists, composers (for instance Gaetano Donizetti’s opera Maria Stuarda, based on Schiller’s play, in 1835), or, more recently, film directors2. Here I shall focus on two plays only, the above-mentioned Maria Stuart by Friedrich Schiller, and Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson’s Maria Stuart i Skotland, from 1864. Schiller is one of the two greatest German writers, though slightly put in the shade by Goethe, Bjørnson is one the two greatest Norwegian writers, though internationally put in the shade by Ibsen. Bjørnson admired Schiller. In 1862, he saw Maria Stuart in Hannover, a drama that he later said to be at the origin of his own Maria Stuart I Skotland3.

2Schiller meant, the ancient Greek tragedy had achieved to transform individuals into types and symbolic figures, to turn history into timeless stories, and that became the ideal he strived to reach in his historical dramas. He poeticized historical facts so as to make them relevant for all times – in particular for his own. Bjørnson had a positive vision of classicism, as an eternally young aesthetic, and a bridge between the ancient and the new4. “Classicism” was for him in the first place Shakespeare and Oehlenschläger, German classicism and the classical historical drama. He meant that history could be used “to give a better explanation of a contemporary situation5” and he was very interested in “the approach to historical reality Schiller had in his works6”.

3Schiller’s Maria Stuart is set in the last days preceding Maria’s death. The former queen of Scotland fled her country and came to England to get protection. But Queen Elisabeth (I) suspected that Maria actually aimed to ascend the English throne, because she had a hereditary right to it. Elisabeth had her hold in confinement at Fotheringhay castle for a number of years. When the play begins, Maria has been formally accused of plotting against the Crown in order to dethrone Elisabeth and take her place. A parliamentary court has just debated the issue, found Maria guilty and condemned her to death. As the sovereign, Elisabeth is the only person who could save her, by granting her royal pardon. For Elisabeth, the decision is extremely hard to make, she is torn between her fear of Maria’s Catholic friends who want to overthrow her, and her conscience and human feelings which forbid her to kill someone who also has English royal blood. Elisabeth decides she will meet Maria. But during the meeting, Elisabeth keeps demonstrating her own power, reminding thereby how powerless Maria is. Maria loses her temper, becomes insulting and calls Elisabeth a bastard. Elisabeth reacts with rage and leaves Maria. From that moment, it becomes probable that the queen will not grant pardon. On her way back from the meeting with Maria, Elisabeth is attacked on the street and only survives thanks to the quick intervention of an old counsellor. That increases suspicions about a Catholic plot. Elisabeth still ponders her decision concerning Maria’s fate. Eventually, she signs the paper with the death sentence, hoping it will never reach its destination. But it does. Maria is informed that she will be beheaded on the following morning. She reacts as a deeply religious person, she confesses her sins to a Catholic priest and is ready to die. When Elisabeth learns of Maria’s death, she feels despaired, and tries to deny her own responsibility.

4Bjørnson’s Maria Stuart i Skotland is set in a time when Maria is queen of Scotland. It begins in March 1566 and ends in the summer of 1567. It shows struggles for power among the Scottish aristocracy, including murders, plots, treachery and military attacks. The queen’s main enemies are Protestants fighting her Catholicism and the Pope’s influence on the country. It becomes rapidly clear that the religious motives are primarily an excuse to seek power. Maria is married to Darnley, a young man she does not love any longer. She spends a lot of time with her Italian Catholic adviser Rizzio. One night, Protestants led by the old Ruthwen attack Holyrood castle in Edinburgh, where Maria is giving a banquet, and assassinate Rizzio. The only one among Maria’s allies who succeeds leaving Holyrood is Bothwell, whom Maria trusts because of his strength and his devotion to her person. Maria tells Darnley she is pregnant and forces him to come with her to Bothwell’s castle of Dunbar. Darnley was one of the conspirators that initiated Rizzio’s murder – and signed a letter craving Maria’s dethronement. Months later, when Maria has returned to Edinburgh, conspirators keep plotting new actions. A number of them change camp. Bothwell is the only one whom Maria can still rely on. He takes part in a conspiracy to kill Darnley. The plot is successful. Bothwell is determined to marry Maria, though she consistently refuses. But in the end, she has no other choice than becoming his spouse. Shortly after Darnley’s death, the nobility breaks up its alliance with Bothwell. While he is away fighting on his own, the noblemen come to Maria and force her to abdicate in favour of her son.

5Although only 64 years separate Maria Stuart i Skotland from Maria Stuart, their form is strikingly different. Schiller’s play is a quintessential classical tragedy. It is generally regarded as “Schiller’s most perfect, most regular, most classical theatrical work7”. It is written in blank verses, in iambic pentameters, as most classical German dramas. The language is distinctly literary, with few interjections. Bjørnson’s prose is closer to standard language, and at the same time, according to Georg Brandes, it has a Shakespearian splendour8.

6Maria Stuart has a symmetric structure: acts I and V are dedicated to Maria, acts II and IV to Elisabeth, and act III to the meeting between the two, with the peripetia in the middle. Maria Stuart i Skotland rather follows the pattern of the Shakespearian historical drama, with a significant narrative dimension. It has an intricated plot that stretches over a year and a half, with a series of unexpected events and many people changing camp at any time. Harald Noreng means that, especially towards the end, it becomes “so complicated that it is difficult for the audience in a theatre not to lose the thread of the story9”. It does require some attention to keep track of who is betraying or helping whom.

7In three respects at least, Maria Stuart I Skotland is a kind of hapax among Bjørnson’s historical dramas. The main character is strikingly different from the other female protagonists, as we shall see further below; the action is not set in the Middle Ages, and not in Norway, but in the Renaissance and in Scotland. That unusual setting might be due partly to the Schillerian model, which, according to Sturtevant, had made a strong impression on Bjørnson10. On the other hand, a character like Bothwell, though living in the 16th century, has medieval, and “Viking” traits11.

8The two plays on Mary Stuart show two different periods of her life. When Schiller’s drama begins, Darnley, Rizzio and Bothwell, the men who will later be Bjørnson’s major male characters, are already dead. But we hear about them in the expositional first act: the spectator has to know what happened to Maria before she became Elisabeth’s prisoner and who she is12. These explanations actually give the main narrative thread in Maria Stuart i Skotland.

9Both works are set in the Renaissance, and offer a similar, rather gloomy image of it. They describe it as a time of political disorder and upheavals. Schiller and Bjørnson lengthily show intrigues and struggle for power. One of the two main traitors in Maria Stuart, Mortimer, who pretends to serve Elisabeth while preparing Maria’s break-out, never existed and was invented by Schiller; the other traitor, Leicester, does have an historical counterpart, but no historical source mentions the love affair he is having with Elisabeth in Schiller’s work13. In the play, he is first supposed to use the queen’s confidence in order to help Maria. But he does not really side with the latter either, and he leaves England as soon as he is about to be exposed. He is as much a villain as Bjørnson’s noblemen who keep betraying the queen and one another, with self-interest as the main motivation. Such a state of mind is bluntly expressed by Maria’s words to Rizzio in Maria Stuart i Skotland: “Many people before you have also been faithful to me; but all of them have had their reasons – reasons that I have seen14…”

10In Schiller’s and Bjørnson’s Renaissance world, concern for morals is not dominating. Yet on that issue, there is again a difference between the two authors. A famous quote from Schiller reads: “The human being is created as a free being, is free / Even if he were born with chains15”. The Schillerian tragedy is revolving around a catastrophe that has already happened or that might happen, and the question is how to react to that catastrophe16. The focus is on individuals, their confrontation with fate and their ability to behave as free human beings through an ethical choice. In Maria Stuart, against a background of lawlessness and corruption, such choices are constantly present in the portraying of the protagonists.

11As a result, Maria and Elisabeth have been largely understood and judged from an ethical point of view. Traditionally, Maria was seen as a woman who once had been frivolous and an accomplice in the murder of her husband Darnley, but who later had felt sincere remorse, and eventually turned into a kind of saint by accepting the death sentence imposed on her, while Elisabeth appeared as a heartless woman, primarily concerned about demonstrating and keeping her power. But some scholars have voiced different, or even opposite views. Karl S. Guthke notes that Maria has been and remains a mondaine as long as possible17. She mortifies herself because of Darnley’s murder, and at the same time she conspires with those who plan her escape. As for Elisabeth, she is not, in my opinion, the negative figure sketched by Barbara Neymeyr, who speaks of “her unrelenting assertiveness18”. Undoubtedly, Elisabeth wishes Maria’s death; but she has some reasons to do so. The Catholic party means that Maria should be queen of England and that Elisabeth must be eliminated. The Catholic Church allows all possible crimes for those who serve its power, and people fighting for it have been granted absolution for all their sins, including sins which are still to be committed19. Elisabeth’s situation is rightly described by Burleigh, who says to the queen: “Her [Maria’s] life is your death! Her death your life20!” In a previous scene, Burleigh has suggested that Elisabeth would approve of the idea of poisoning Maria slowly, so as to have her death look natural21; whether that is true or not remains unclear. But to accuse Elisabeth of “murderous hardness, with which she treats her challenger in the end22”, as Neymeyr does, is to go too far. On the contrary, during the whole play we see Elisabeth hesitating to sign the death warrant and eventually, once she has signed it, she wishes it will not be handed over to the executioner. If she did have a murderous hardness of heart, she would sign the warrant immediately. Then, the tragedy would end at the beginning of act II – and, actually, there would not be any tragedy. Maria Stuart is structured by Elisabeth’s dilemma between keeping her power, saving her own life, and obeying the moral law which forbids to kill kinspersons. In a way, we might regard Elisabeth as the main character of the drama. Although she tries to deny responsibility at the end, she is the one who must and who can make the decision. Her situation contrasts with Maria’s, which is mainly passive. Maria has hardly any possibility of choice, as her fate is depending either upon Elisabeth’s will or upon the plots of the Catholic party. But when she faces first possible, then certain death, she does not react with fury, denial or despair, she behaves as a free human being and prepares to meet her fate in a dignified manner. She is also a tragic figure. Karl S. Guthke calls Schiller’s play a “double tragedy23”.

12Maria Stuart i Skotland is not a tragedy in a Schillerian sense. It does not seem possible to find in it a moment that would be the peripetia. It stretches over a relatively long time, goes from bad to worse and ends in a catastrophe. Power seems to be the main issue, struggle for it is constant.

13The characters are agents or victims of history, sometimes both. But some of them at least are more than that, they are individuals with complex personalities. Darnley, for instance, though he is married to the queen, is not at all interested in politics, the only thing that counts for him is his love for Maria; he is involved in the plot to kill Rizzio, but only out of jealousy. Bothwell, who feels at home in the cold, foggy, stormy and wild landscape of Scotland, who considers himself a descendant of Vikings24, and is also, for Brandes, “a genuine Renaissance personality25”, has traits of a fabulous creature. He is resolute and brutal, one-eyed, ugly and very strong.

14But the most interesting character in this play is undoubtedly Maria. She has little in common with Schiller’s pious but always passive and slightly dull Maria. In Schiller’s tragedy, Maria herself declares: “I am nothing more any longer than Maria’s shadow26”. Bjørnson’s drama takes place before captivity broke the queen of Scots. She is lively, charming, cruel and cynical, intelligent, eager to show her power. She is more interested in politics than in love: “Really, I have come to Scotland for something else than – to love27!” she says. But she also knows that she is alone and cannot rely on anybody. In a monologue, she asserts: “my own brother turned into an agitator, and I must protect myself against my council as against a snake that I am locked in with in the same room28.” Nevertheless, she is determined to be up to her royal function: “Where I am placed, that is where I have to take action29”, she declares. At the beginning of the play, she appears a rather unpleasant person, she is both frivolous and authoritarian, she enjoys hurting others. Later on, the more her situation deteriorates, the more tenacity she shows. Even when defeated, she has the will to carry on actively shaping history and her own life. She remains dignified. When she is forced to accept something she does not want, her disapproval is clearly visible. She needs Bothwell to fight for her interests, but she certainly does not love him and lets him know she does not. While Schiller’s Maria is said to have been an accomplice of her husband Darnley’s murder because she was blinded by a wild passion for Bothwell, Bjørnson’s Maria is forced by Bothwell to marry him but she resists him as long as possible and never shows any sign of consent. Presumably, such a character needed the historical distance to be acceptable. Harald Noreng means: “if he [Bjørnson] had presented women of his own Christian and middle-class contemporary background with such wild passions […] he could have repelled his public30.” Maria is an intricate figure torn by the difficult situations she is facing. “I feel as if I was made of many pieces, and cannot gather them31”, she says, certainly with right. Neither the spectators nor herself can fully understand her. “You cannot really grasp her being32”, writes Brandes. To him, her incoherent personality was a weak point of the drama. To us, it might make her a modern character, much more modern than Schiller’s.

15At any rate, Bjørnson’s Maria never forgets that she has power, that she actually is supposed to be the most powerful person in Scotland. We may wonder if it is not difficult for her, as a woman, to be accepted as a sovereign in the 16th century. As a woman, she cannot participate in wars, which are frequent in her days, and she is dependent on men fighting for her cause. Some male characters insinuate that she is not fit to reign because of her female temper. But all those men are her enemies; the text as a whole offers little support for such an opinion. Many people conspire to dethrone Maria, but their main reason is her Catholicism in a country with a Protestant majority, and things would hardly be different with a male Catholic king. In Bjørnson’s first historical dramas, all female protagonists only live for the man they love, while the men have other concerns than love. That was pointed out by Harald Noreng, who also noted that Maria Stuart i Skotland is an exception, with an opposite relationship between husband and wife: there is nothing else in Darnley’s life than his love for Maria, while Maria is giving him but little attention, does not love him any longer – if she ever did – and says so openly. The reason why she can humiliate him is obviously her being the queen. In most societies, men usually have more power than women. In Maria Stuart i Skotland, when social and political power changes sex, mental domination does it as well.

16On that issue, the counterpart of Bjørnson’s Maria in Schiller’s play is not Maria the prisoner, but Elisabeth. Both queens are aware of women’s bodily inferiority, and both reject the notion of subsequent intellectual and moral inferiority. To Bjørnson’s Maria, a man who makes use of physical strength against a woman is demonstrating sheer bestiality and loses his quality as a human being. To Rizzio’s aggressors who have come to her rooms and try to thrust her away, she says: “The biggest sin men can commit is to make a woman feel her powerlessness33”, and to the ruthless Bothwell, she declares: “Strength and beauty have sometimes had power over me – brutality has never had any34!” Schiller’s Elisabeth reacts in a similar way. One of her counsellors, Talbot, excuses Maria’s complicity in Darnley’s murder by arguing that she was blinded by her passion for Bothwell, and pronounces the famous sentence: “woman is a frail being35.” Elisabeth replies immediately and sharply: “Women are not weak. There are strong souls/ in that sex – In my presence, I do not want/ to hear anything about the weakness of the sex36.”

17Generally speaking, Schiller meant that by nature women were unable to rule a country. His Maria illustrates that opinion. She cannot resist her desire to be attractive to men, so that she became “men’s plaything37” and for that reason “was unable both to keep the Scottish throne or to conquer the English throne38”. Schiller thought exceptions were possible, if a woman renounced feminine charm and sensuality and if she was capable of controlling her emotions, that is to say, if she mentally was a man, according to his time’s assumption that self-control was a characteristically male quality39. His Elisabeth is such an exception. But as far as our two dramas are concerned, it seems to be a trait they have in common: they do not mean that nature makes it totally impossible for a woman to exercise power. They do not deal extensively with the question, which might suggest that this opinion is final. Besides, in both plays, the main question is not women in power, but power, in general.

18Schiller and Bjørnson lived in times when new ideas and dramatic events disrupted societies, the French Revolution for the former, the question of nationality for the latter. Their 16th century is to some extend a blown-up image of their own world as they perceive it. It is characterized by disorder. In Maria Stuart i Skotland, Bothwell reminds Maria that: “Four rebellions have shaken your short time of reign40.” Otto W. Johnston stresses that in Maria Stuart, Schiller shows “Conspiracies and lust for power on the part of the Church, the state threatened by the nobility of the court, by deception, corruption, desire for revenge41”.

19Against such a background, the authors reflect on the notion of right government. While Barbara Neymeyr speaks of “Elisabeth’s claim to absolute power42”, Otto W. Johnston points out that Schiller deals with the issue of legitimate power: “Maria grounds her claim to the throne on the feudal system of inheritance rights; on the contrary, Elisabeth, whose inheritance rights are questioned, justifies her reign pragmatically, as the reign of a competent private person that the people and the Parliament have mandated to carry out their policy43.” When Maria Stuart was written, the legitimacy of power had just been fundamentally rethought by the French Revolution. The revolutionary assertion was that power had to be based on the “general will” of the people. The question was still a matter of great concern for Schiller, who had received the title of “Citizen of the French Republic” in 1892 and sympathized with the Revolution, at least at the beginning. For him, a reader of Kant, hereditary monarchy is outdated. The sovereign must receive his legitimacy from the people and serve the people. In the first scene with Elisabeth, she appears to be moved by a Kantian sense of duty. She does not wish to get married, but she nevertheless agrees to marry a French prince, because it will ensure peace to the country and the throne needs an heir. “Kings are but the slaves of their office44”, she says. She also means that she makes her people happy: “Not enough, that this country now enjoys blessings45.” Maria has an opposite conception of power, as granted by genuine royal blood only. At the end of her confrontation with Elisabeth, who keeps humiliating her, she bursts out: “The throne of England is profaned / by a bastard […] / – if law prevailed, you would now lie before me / in the mud, for I am your king46.”

20In Bjørnson’s drama, Maria is also a hereditary monarch, in that case of the Scots. To her, it means that she has been placed on the throne by God, and when someone questions her power, she refers to the divine will. In act III, she meets John Knox, the leader of the middle-class Presbyterians, a character that reminds of haugianism and pietism, which were dominant in Norway in the 1860s, as Georg Brandes pointed out47. Maria explains to Knox that she is a Catholic but wants the different religions to live together in a tolerant way in Scotland. But Knox is a fanatic and believes his faith is the only true faith, so that he could not compromise with other beliefs. Then Maria gets angry and declares: “The king in the Lord’s Anointed48”, and “priests that incite the people to rebellion against their authorities are an abomination for the Lord – and we shall not tolerate them within our borders49”. She conceives of herself as an absolute monarch.

21Maria Stuart i Skotland was written in the year when Denmark was attacked by Prussia and Austria, did not get military help from Sweden-Norway and lost the southern part of Jutland. Bjørnson supported scandinavism, a political movement that aimed to tighten the bonds between the Scandinavian countries. Denmark’s defeat was a defeat for scandinavism. There is no direct link between the play and the political background of 1864, though (or possibly because?) it must have shaken Bjørnson deeply. Francis Bull wrote that Maria Stuart i Skotland “is a totally untendentious […] work of art50”.

22The play is not tendentious in a narrow sense of the word. But I do not think it is neutral or indifferent. Bjørnson was in favour of an independent nation of free citizens where decisions are made according to the people’s will – and diverging opinions are tolerated. In 1881, he declared about Norway in the 1830s that “the national feeling began changing. Until recently, it had mainly been the feeling of belonging to the State, then it began becoming a feeling of belonging to the people; […] when the national feeling became democratic and freedom became its ideal, it met the Norwegian people’s heart51.” Bjørnson does not share his Maria’s political views. Her – often arbitrary – power is constantly challenged – unfortunately, mostly by the wrong persons. Many of her adversaries are aristocrats, but they are allied with the middle class, at least temporarily. The author does not approve of absolute monarchy, nor of the noblemen’s attitude, neither of their doings, nor of their motivation: their aim is not to put an end to absolute power, it is to conquer at least part of it.

23Bjørnson gives us a bleak image indeed of Renaissance Scotland. That image seems to be radically modified on the last half-page of the text, as John Knox arrives, not among aristocrats, but with “the people”, and says:

What the nobility of Scotland has done today is certainly for the best; for everything is for the best. But today, they may not lay the impure hands of the fight on that banner; for it is not under Murray’s, not under Morton’s, not under Lethington’s flag, it is under Scotland’s, under the national flag that Scotland will triumph over all its misery52.

24That sounds like a happy ending, at the last second. Knox is supported by the people, he speaks in the name of the nation, and he has won. Nevertheless, we may not forget that Knox is a fanatic and that there will not be any form of tolerance if he comes to power. So I find it more appropriate to call the last lines of the play a make-believe happy ending. Something that is not unusual in Bjørnson’s works, where we find other examples for that kind of ending, as, for instance, in Over Ævne II.

25Like Schiller, Bjørnson obviously enjoyed painting the Renaissance as a corrupted, but colourful time, while partly using a geographically and historically exotic setting to deal with contemporary issues – like Schiller. By choosing another moment of Mary Stuart’s life, he could portray another woman. His Maria is not only different, she is more complex, not fully comprehensible, a more modern character than Schiller’s. The aesthetic of Maria Stuart i Skotland is anticipating the aesthetic of the turn from the 19th to the 20th century.

1 See Barbara Neymeyr, “Macht, Recht und Schuld. Konfliktdramaturgie und Absolutismuskritik in Schillers Trauerspiel Maria Stuart”, in Günter Saße (dir.), Schiller. Werk-Interpretationen, Heidelberg, Universitätsverlag Winter, 2005, p. 108. In this paper, I use the names “Mary Stuart” and “Elizabeth” when referring to the historical figures, and “Maria” and “Elisabeth” when referring to the characters in the plays.

2 The first film was probably the American silent film The Execution of Mary Stuart in 1895. It was 18 seconds long. The most famous one is John Ford’s Mary of Scotland, in 1936, with Katharine Hepburn as Mary, and the latest one, Mary Queen of Scots, directed by Josie Rourke, was released in 2018. Recently, the television series Reign, released in 2013, was based on Mary Stuart’s life.

3 See Albert Morey Sturtevant, “Bjørnson’s ‘Maria Stuart i Skotland’”, in Scandinavian Studies and Notes, University of Illinois Press, August 1917, Vol 4, no 3, p. 203-219; According to E. Hoem, Bjørnson saw Maria Stuart in Hannover in December 1860. See Edvard Hoem, Villskapens år. Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson 1832-1875, Oslo, Forlaget Oktober, 2009, p. 328.

4 See Ann Schmiesing, “Brennende iver, men liten forståelse? Om Bjørnsons lesning og oppsetning av Goethe og Shakespeare”, in Liv Bliksrud, e. a., red., Den engasjerte kosmopolitt. Nye Bjørnson-studier, Oslo, Novus Forlag, 2013, p. 97.

5 Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson, Gro-tid. Brev fra årene 1857-1870, red. Halvdan Koht, Christiania, Gyldendal, 1912, Bind 1, p. 254. Quoted in Schmiesing, op. cit., p. 97: “til større Forklarelse af et Nutidsforhold”.

6 Schmiesing, op. cit., p. 97: “den tilnӕrmingen til historisk virkelighet Schiller hadde i sine verker”.

7 See: Adolf Beck, “Schiller. Maria Stuart”, in Benno von Wiese, Hg., Das deutsche Drama. Vom Barock bis zur Gegenwart, Bd. 1, Düsseldorf, 1968, p. 307.” Quoted in Neymeyr, op. cit., p. 105.

8 See Georg Brandes, Det moderne Gjennembruds Mӕnd. En Rӕkke Portrӕter, Kjøbenhavn, Gyldendalske Boghandels Forlag, F. Hegel & Søn, 1883, p. 31.

9 Hararld Noreng, Bjørnstjerne Bjørrnsons dramatiske diktning, Oslo,Gyldendal norsk forlag, 1954, p. 136: “så innviklet at det blir vanskelig for et teaterpublikum å holde fast i handlingstråden”.

10 See Albert Morey Sturtevant, op. cit., p. 203.

11 See Claire McKeown, “The Sea Kings of the North. Scandinavian Scotland in Nineteenth Century Literature”, Études Écossaises, 19/2017, http//journals.openedition.org/etudesecossaises/1197, downloaded 2024-09-12.

12 See Friedrich Schiller, Maria Stuart, Act I, Scene iv, in Schillers Werke in fünf Bänden, Bd 2, Köln, Berlin, Kiepenheuer & Witsch, 1959, p. 295-298. The English translation is mine.

13 See Karl S. Guthke, “Maria Stuart”, in Helmut Koopmann, Hg., Schiller-Handbuch, Stuttgart, Alfred Kröner Verlag, 1998, p. 419.

14 Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson, Maria Stuart i Skotland, in Samlede vӕrker, mindeutgave, fjӕrde bind, Kristiania, Kjøbenhavn, Gyldendalske boghandel Nordisk forlag, 1911, p. 140: “Mange har også før dig vӕret mig tro; men de har alle hat sine grunner – grunner som jeg har set…” The English translation is mine.

15 Friedrich Schiller, “Die Worte des Glaubens”, in Friedrich Schiller Archiv, downloaded 2024-09-12, https://www.friedrich-schiller-archiv.de/gedichte-schillers/lange-gedichte/die-worte-des-glaubens/: “Der Mensch ist frei geschaffen, ist frei, / Und würd er in Ketten geboren”.

16 Helmut Koopmann writes: “Maria Stuart war nichts anderes als ein Versuch, beide Furchtsamkeiten miteinander zu verbinden: dass etwas geschehen könne, nämlich der Tod Marias, verbindet sich mit der Einsicht, dass etwas geschehen war, nämlich die von ihr verschuldete Mordtat.” (H. Koopmann, “Schiller und die dramatische Tradition“, in Koopmann, op. cit., p. 151.)

17 See Guthke, op. cit., p. 420-427.

18 Neymeyr, op. cit., p. 111: “ihre unerbittliche Selbstbehauptung”.

19 Schiller, Maria Stuart, III, vi, op. cit., p. 363.

20 Ibid, II, iii, p. 325: “Ihr [Marias] Leben ist dein Tod! Ihr Tod dein Leben!”

21 Ibid, I, viii, p. 317.

22 Neymeyr, op. cit., p. 111: “mörderische Härte, mit der sie schliesslich gegen die Konkurrentin vorgeht”.

23 Guthke, op. cit., p. 415 and p. 421: “Doppeltragödie”.

24 See McKeown, op. cit.

25 Brandes, op. cit., p. 29: “en ӕgte Renӕssance-Personlighed”.

26 Schiller, Maria Stuart, III, iv, op. cit., p. 359: “Ich bin nur noch der Schatten der Maria”.

27 Bjørnson, Maria Stuart i Skotland, op. cit., p. 130: “Sandelig, jeg er kommet til Skotland for annet ӕn for at – ӕlske”.

28 Ibid., p. 143: “min egen bror blev en oprører, og mot mit råd må jeg beskytte mig som mot en slange med hvem jeg er innestӕngt i samme rum”.

29 Ibid., p. 143: “Der jeg er sat, må jeg virke”.

30 Noreng, op. cit., p. 57: “om han [Bjørnson] hadde presentert kvinner fra sitt eget kristne og borgerlige samtidsmiljø med slike ville lidenskaper […] kunne han ha støtt sitt publikum tilbake.”

31 Bjørnson, Maria Stuart i Skotland, op. cit., p. 142: “Jeg føler mit vӕsen som i mange stykker, og kan ikke samle dem.”

32 Brandes, op. cit., p. 29: “Man faar ikke ret fat paa hendes Vӕsen”.

33 Bjørnson, Maria Stuart i Skotland, op. cit., p. 153: “Den største synd som mӕnn kan begå, er at la en kvinne føle sin avmagt.”

34 Ibid., p. 192: “Styrke og skjønhed har undertiden øvd magt over mig – råhed aldrig.”

35 Schiller, Maria Stuart, II, iii, op. cit., p. 327: “ein gebrechlich Wesen ist das Weib.” This sentence was probably inspired to Schiller by the line in Shakespeare’s Hamlet (I, ii): “Frailty, thy name is woman.”

36 Ibid., II, iii, p. 328: “Das Weib ist nicht schwach. Es gibt starke Seelen / In dem Geschlecht – Ich will in meinem Beisein / Nichts von der Schwäche des Geschlechts hören.”

37 Ulrich Kittstein, Das Wagnis der Freiheit. Schillers Dramen in ihrer Epoche, Darmstadt, wbg Academic, 2023, p. 391: „Ein Spielball der Männer“.

38 Ibid., p. 391-392: “konnte weder den schottischen Thron behaupten noch den englischen erobern.”

39 See ibid., p. 392.

40 Bjørnson, Maria Stuart i Skotland, op. cit., p. 173: “Fire oprør har rystet Eders korte regjeringstid.”

41 Otto W. Johnston, “Schillers politische Welt”, in Koopmann, op. cit., p. 58: “Verschwörungen und Machtgier der Kirche, Bedrohung des Staates durch den Hofadel, Verstellung, Korrumpierbarkeit, Rachgier.”

42 Neymeyr, op. cit., p. 111: “[d]er absolute Machtanspruch Elisabeths”.

43 Johnston, op. cit., p. 58: “Maria stützt ihren Thronanspruch auf die feudalen Erbfolgeregelungen; Elisabeth dagegen, deren Erbfolgerecht umstritten ist, begründet ihre Herrschaft pragmatisch als die einer geeigneten Privatperson, die Volk und Parlament zur politischen Mandatsträgerin erkoren haben.”

44 Schiller, Maria Stuart, II, ii, op. cit., p. 321: “Die Könige sind nur Sklaven ihres Standes.”

45 Ibid., II, ii, p. 321: “Nicht genug, / Dass jetzt der Segen dieses Land beglückt”.

46 Ibid., III, iv, p. 361: “Der Thron von England ist durch einen Bastard /entweiht […] / – Regierte Recht, so läget Ihr vor mir / Im Staube jetzt, denn ich bin Euer König.”

47 Brandes, op. cit., p. 29. See also: Sturtevant, op. cit., p. 218. Haugianism was a strict Protestant denomination that had been established in Norway by Hans Nilsen Hauge at the beginning of the 19th century.

48 Bjørnson, Maria Stuart i Skotland, op. cit., p. 169: “kongen er Herrens salvede”.

49 Ibid., p. 171: “prӕster som rejser folket mot sin øvrighed, er Herren en vederstyggelighed – og vi vil ikke tåle dem innen vore grӕnser!”

50 Francis Bull, Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson, Kristiania, H. Aschehoug & Co (W. Nygaard), 1923, p. 25-26: “et helt tendensfrit […] kunstverk”.

51 Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson: “Tale ved Afsløringen af Wergelands-støtten. 17de Mai 1881”, in Agora – Journal for metafysisk spekulasjon, nr. 1-2/1990, Institutt for Filosofi, Blindern, p. 216: “Netop den Gang begyndte Nationalfølelsen at forvandle sig. Den havde hidtil isӕr vӕret en Statsfølelse, den begyndte nu at blive en Folkefølelse; […] da Nationalfølelsen blev demokratisk og Friheden dens Ideal, traf den det norske Folkehjerte.”

52 Björnson, Maria Stuart i Skotland, op. cit., p. 195: “Hvad Skotlands adel har gjort idag, er visselig til det gode; ti alt er til det gode. Men da skal de idag ikke lӕgge kampens urene hӕnder på dette banner; ti det er ikke Murrays, ikke Mortons, ikke Lethingtons, det er Skotlands, det er det nationale tegn, hvorunder Skotland skal sejre over al sin jammer.”

Actes de la journée d'études organisée à l'Université de Strasbourg en 2024, publiés par Florence Fix, Corinne François-Denève et Solenne Guyot

© Publications numériques du CÉRÉdI, « Actes de colloques et journées d’étude », n° 35, 2025

URL : https://publis-shs.univ-rouen.fr/ceredi/2057.html.

Quelques mots à propos de : Annie Bourguignon

Université de Lorraine

CEGIL

Annie Bourguignon est professeur émérite de l’Université de Lorraine. Ses domaines de recherche principaux sont la littérature scandinave des xixe et xxe siècles, la littérature non-fictionnelle et la littérature comparée. Outre de nombreux articles en lien avec ces sujets, elle a publié Der Schriftsteller Peter Weiss und Schweden (Röhrig Universitätsverlag, 1997) et Le Reportage d’écrivain. Étude d’un phénomène littéraire à partir de textes suédois et d’autres textes scandinaves (Peter Lang, 2004). Elle a également co-dirigé un grand nombre d’éditions d’actes de colloques.

Annie Bourguignon is Professor Emerita at the Université de Lorraine (France). Her main fields of research are Scandinavian literature of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, non-fiction literature and comparative literature.

In addition to a series of articles in relation with those subjects, she has published Der Schriftsteller Peter Weiss und Schweden (Röhrig Universitätsverlag, 1997) and Le Reportage d’écrivain. Étude d’un phénomène littéraire à partir de textes suédois et d’autres textes scandinaves (Peter Lang, 2004) and co-edited several proceedings of academic conferences.