Sommaire

5 | 2020

Unmoored Languages

This volume explores the complex relations developing between a literary text and the world beyond the representational function. Not content to capture, narrate or describe the existing world, writers keep creating autonomous worlds and inventing new languages to account for yet unmapped territories and experiences. As the materiality of language and its poetic quality come out, the sounds, rhythms and visual effects of the text become living milieu rather than material or simple instruments subordinated to thought. Though the effect first produced upon the reader may well be of strangeness or obscurity, such unmooring of language warrants a valuable extension of language likely to bring back to the reader buried, unsuspected emotions and aesthetic experiences, should she be willing to adopt an open type of reading, more fluid than the automatic system of conventional associations on which reading largely relies. In this collection, writers and literary scholars from the U.S. and France focused on the nature of the mutations to which unmoored language is submitted, as well as on the various ways in which the text makes sense in spite of all. How to describe that which exceeds language rather than avoid the confrontation by relegating it into the vague category of the ineffable? Throughout, literary, linguistic or philosophical analyses have as their horizon the vision of language reflected by the unmoored text, as well as of the relations between language and the world.

- Anne-Laure Tissut et Oriane Monthéard Introduction

- Rob Stephenson Trans(positions)(mutations)(formations)itions

- Thomas Byers Weighing Anchors: The Pleasures of Readers

- Monica Manolescu Lectures de la déliaison dans The Flame Alphabet de Ben Marcus

- Stéphane Vanderhaeghe Tentative d’approche d’une fiction spéculative

- Léopold Reigner Interwoven readings: R. Brautigan’s Trout Fishing in America and R. Stephenson’s Passes Through

- Mélissa Richard Merged readings

- Sarah Boulet Shut up and fill in the gaps with something multifaceted

- Paule Lévy Lost in Translation : Figures de la déliaison dans Leaving the Atocha Station de Ben Lerner

- Judith Roof Jazz Mislaid Jazz: Rhythm has No Boundaries

- Yannicke Chupin “Unmoor your thinking for an instant” Autoannotation et déliaison dans The Mezzanine (Nicholson Baker) et Brief Interviews with Hideous Men (D.F. Wallace)

- Melissa Bailar Lipogrammatic Criticism: Inspirations from La Disparition

- Florian Beauvallet Les formes déliées de Kapow! d’Adam Thirlwell : avatars d’une pensée en mouvement

- Zach Linge “Theory of/and Original Writing After Deconstruction”

- Maud Bougerol Ré-ancrer la langue ? – “Moran’s Mexico: A Refutation by C. Stelzmann” de Brian Evenson

- Célia Galey-Gambier Sharing and Distributing the Sensible in Jackson Mac Low’s Dance-instruction-poems The Pronouns (1964)

5 | 2020

“Theory of/and Original Writing After Deconstruction”

Zach Linge

Staring from a selection of his own poems and introduction notes about the circumstances out of which they emerged, Zach Linge explores the complexities of the poetic “I” necessarily rooted in though detached from the physical individual it originates in. He also ponders on poetic language drifting away from reference while creating a presence of its own that refashions representationwhile framing the “I” as a poetic “relational construction”.

1This letter is something of an exercise in good faith that the reader would permit me to reflect on the situation out of which the accompanying poems emerged, as well as allowing me to speak to the poems’ intentions and how I came to share them at a conference in Rouen on unmoored and unmooring languages. I am afraid a letter like the one I am writing now cannot appeal to all readers. The following poems, however — should they be printed unaccompanied by such a letter —, might frustrate the reader who searches for their relevance to the conference topic. My purpose, then, is to speak to how these exercises negotiate the conference topic, that their inclusion might interest and make sense to the reader. I hope to mitigate any potential offense by keeping my comments brief.

2The first point I wish to address is my use of the personal pronoun — which I employ here under the suspicious auspices of the epistolary genre, one in which the “I” seems selfsame with and apparently essential to the speaker who is, in this case, also the writer. But the identity of an “I” is always already at least one step removed from any physical person. The reader identifies the construction of that identity as linguistic, contained in the symbolic, whether written, spoken, or otherwise presumed. Daniel Katz argues that the so-called “New York School” poet James Schuyler, for example, brands his own “letter-poem” genre — a genre that “is not only about the becoming epistolary of poetry, but also a general epistolarity in which description cannot be thought outside of pointing, appropriating, addressing and exchange — signing in every sense of the word” (157). What Schuyler brings to the fore, in his combinatorial letter-poems, is also evidenced in the rest of his work, however subtly, and inspires mine: there exists an infinite referentiality in all things poetry might apprehend, and further, these things exist as we know them only within that network of reference. Any “I,” as I see and use it, is more an attempt at signification—which is to say an attempt to make, categorize, and communicate sense—than the presence that “I” may presume. And yet, because language is selfsame with what it signifies, language, too, is a similar presence. What is signified, however, cannot be apprehended without a signifier; but a signifier can and will operate without its purported signified. This is the operational principle I believe allows for the unmooring of language, generally, and also the attached poems’ foremost inspiration: Given language needs no material object in order to represent, what are the spaces in which language represents representing best? I think it starts with the “I.”

3These ideas are obviously neither new nor my own. The original title for the attached manuscript was “Theory of/and Original Writing After Deconstruction” — a title which I hoped would signal the poems’ aims and influences, from which these ideas were derived. “After,” as I saw it, would place the poems in time: they happened after the critical camp borne of general linguistics that emphasized language’s relational qualities, subordinated the author function, and challenged assumptions. My title now seems to me too obvious. I might as well have titled the manuscript “2016,” subtitled it, “That’s when I wrote these.” The word “After,” however, does not only operate temporally. The word also means “inspired by,” as in: “These poems are inspired by and take certain tenets of deconstruction into account.” This might also seem too obvious but, as Marjorie Perloff observes, poetry of the twenty-first century often fails to challenge the Romantic paradigm of the lyric “I” that precedes deconstruction by over a century. Such poems suggest “that there is no such thing as cultural construction, no social class, race, or gender”; the abstract “I” that typifies this poetry “simply addresses other such abstract selves” (Perloff 252). My aim with this “After,” then, is to say These are not those poems; these poems’ speakers don’t believe in themselves, don’t believe in a self’s independence from its signification.

4I tend to agree with Perloff that abstraction perpetuates problems of assumed identities in contemporary poetics. Who we represent, as writers, is a problem that persists along the lines of privilege so long as the lyric “I” is a generalized construction wrought by persons of particularized experiences. So long as the poet is a person, the poem represents that person. The poet is the poem’s chief characteristic — despite whatever intention that poet might have to speak in the voice of the common man, for instance — whenever s/he is the primary force responsible for constructing the poem. But we know that language needs no object. We know symbolism functions devoid of any interlocutor. This is the following poems’ second major concern: How might disrupting the process of construction, by paying particular attention to the poet’s role in making a poem, further distance the presumed signified of the “I” from a poem’s actual signification? Specifically, when the poet operates less as a writer than as a mediator of text, can the primacy of the source text successfully supersede the lyric “I” as, rather than an essentially autobiographical configuration, a relational construction?

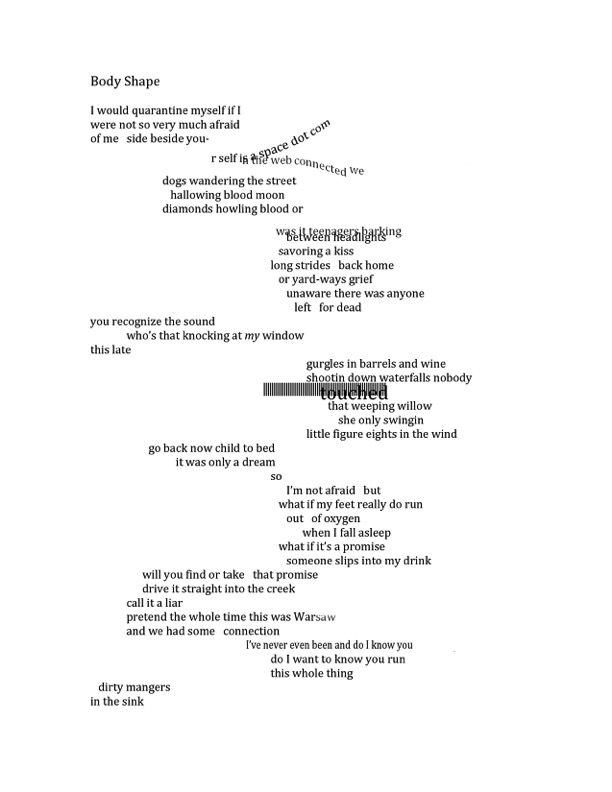

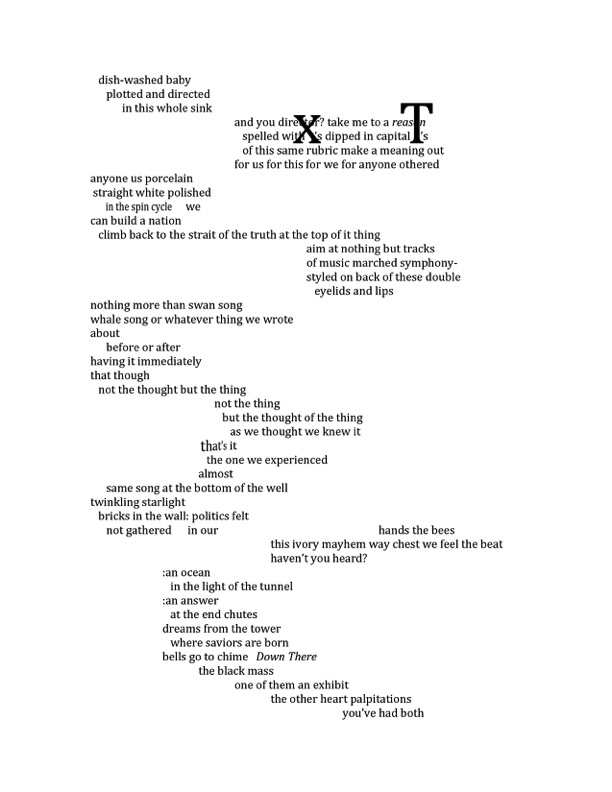

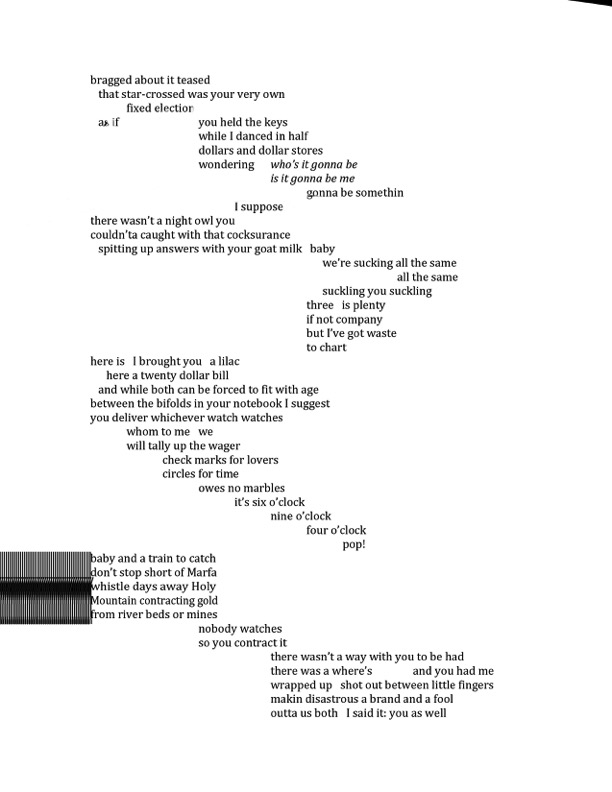

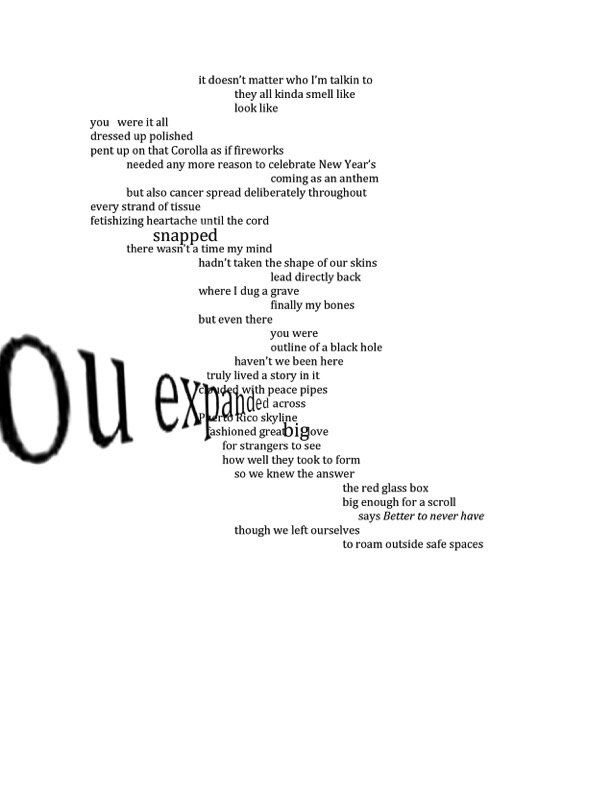

5The following poems are divided along these lines. The first six poems employ conventional, confessional speakers who recount and attempt to make sense of experiences using syntactically conventional, logical, and accessible language. These poems’ success depends in part upon the reader’s willingness to suspend disbelief, to accept generalized outer and inner worlds. The seventh poem, “Body Shape,” maintains the abstract lyric “I,” but challenges language’s ability to represent lived experience, emphasizing language’s materiality, instead—how words make music; how that music makes a sense of its own for the reader, independent from meaning; how competing allusions, dialects, and symbols can make a poem “about” something more than what it seeks to represent. “Body Shape” demarcates this manuscript’s transition to a focus on the poem as mediator. The remaining six poems operate within this focus to resituate the poet through cento, group-sourced writing via prompt, found and erasure poetry, and, finally, a mock-lyric ars poetica in which the speaker could have been, well, anything.

Whale Sounds

6I knew not to tell you that Dad’s jaw clicking means he’s thinking, not angry, which is when his lips shrink into one thin line below his mustache, which is now because he’s watching the road, clicking and shrinking, and the Starburst wrappers are crinkling too loudly so I open them slower. Starbursts because you reported a breakthrough, which means I dug my thumbnail deep enough into the spine to make actual tears when I told you something I knew you’d think was sad, so Dad buys Starbursts because he told us to be honest and a break- through means crying, which is honest, but I knew he didn’t mean it. So I told you about Allison with cardboard boxes under her bed overflowing Butterfinger wrappers dripping blood when Mom told me to get her for our family movie Friday. We were at the part where the Emperor gets turned into a llama, so I pretended to be a llama because your eyes were bigger than most grownups’, and your shoulder-length white hair was not Air Force, so either you’re especially good at making me tell things I don’t want to tell or you’re an idiot, and I wanted to keep my groove. Allison’s the reason Dad’s clicking, because he wants her happy but doesn’t know how much it costs; shrinking because he thinks it’s the last week he’ll see us. I want to tell him everything I didn’t tell you, but all five pink Starbursts are clogging up my throat and, besides, the Air Force doesn’t require him to ask the questions he isn’t so set on getting answers to. My tummy makes whale sounds and my mouth begins to water; Dad’s passing everyone on the highway and it feels like you’re a car behind trying to hit us with a secret. You said This stays between us, but so did my friend Maureen when I told her about the rape and she said she wouldn’t tell. But she did tell, because Vice Principal Skintags asked me why I said that I would cut her throat and I said I never told her I would slit her throat. He said cut, she said slit, I said slit; I said Fine: because it was a secret nobody was supposed to share but I had to tell someone. Nobody’s falling for the We Keep Secrets game, Dr. Ivers. Mama told me what and what not to talk about, told me off for telling Maureen. We’re driving to move Allison from the hospital to inpatient in Boise. Dad asked How did therapy go. I said Good, then fell asleep. We had this conversation for eight years until I went to college. You don’t know that because we left Idaho together, as a family. I’m not sure what you wanted, but I know we didn’t give it to you.

Good as it Gets

7I burn my palms frosty whiteagainst the pink of my neck

with a physical memory of your tongue,

that watery dragon

slithering down my nape.

8Sweating stones,

arms between the pillars of your

two-ton hug I was

hot babe,

stewing in citric acid.

Orison to the Child Heart

9You as the lilac raindrop’s passage from sunset coral cloud

low between the slopes of a submarine ravine that is you,

as the shallow divide between each peak of a fingerprint

brushed across the many wrinkled laugh of an elephant calf.

You as the space beyond the cityscape. Where the Pacific

10teaches value in shades of phosphorescence, you as the sky,

not a notion or a memory, but the thing better done

than said—as staring up into, as building castles inside.

You as the savory cobalt blush that makes the eye squint, as

drawn in reverse, each pail instead filling water in the well

11with wishes. You as the key whistles high behind Franklin’s kite,

as the pale hand that drops the apple, as every nightmare

folded into sheets with butterfly kisses. You as lipstick.

You as the stack of suitcases that guard our jewels, as ribbons

tied into knots. You as the vermillion glow of the luna

12moth, the silk spun of a thousand worms into cloth, as the peace

sign sketched in sidewalk chalk by the tiny brown hand that belongs

to someone who paints the world in velvety pastel, who has

not yet forgotten. You as the wail of the common loon, two

opposing windows left ajar over the alleyway. You as the remedy.

The Two of You Together, Each of You Alone

13The kindest thing I did for Darleen was to smoke my father’s brand of cigarettes to and through esophageal cancer. She then had some body to blame, and at least the luxuries of blame when, after, she had only her own cold hands to hold. When the ride-horse cantered, panting, through the forest edge, increasing the breeze of the ache between her ribs with it, and Darleen’s one living memento was an iron stirrup spun on the loom into the Persian rug—not a gallop, then, or the canter, anymore, but a calm after those fists. But those fists, and those fists, before, pulling at fadings in the fabric, beating at the seams before the black mare vanished into the forest. Darleen was kneading wet knuckles, on her knees, in my absence, and alone, in her teeth at the bit between her jaws, whinnying into tapestry stitches and back upward at the ceiling: gasps with horseshoes pinging off the plaster, wondering how loudly she would have to cry before I and those hooves would sink, back through the wailing wall billowing in screams, back into the bedroom, and back across that kitchen table, where she left an untouched, loaded ashtray beckoning me home, its compact of grey wet in a cake waiting to be cut open by the flame of a fresh-lit cigarette, please, she says. Still the thud of blood and mucous hitting my handkerchief—the sound that means there is no God, Darleen, and I had only myself to blame. She tells herself this, too, and again, louder. She’s tugging at her eyelids, at peace, which is how I know I buried the living, and she thanks me. Thanks me for the rain. Thanks me for that summer on the swing set. Thanks me for leaving every memory in its place. She says this as she scrubs the yellow off the walls.

X’s and O’s

14He’ll be swiveling on his chair

when his arm falls,

having forgotten what it’s reaching for—

15and all about you rustling, with holes in their pockets,

each and every angel is terrible.

16*

17It’s only morning, your laces tied

his pulled into a knot, then again

your laces

unthreaded

over the tongue

when night falls—

18leaning into his shoulder

with the sharp of your elbow.

19*

20He probably won’t stay.

He’ll text you an I’m sorry

if any hopes were dashed—

as if anyone says dashed—

21and you’ll ask him not to text again.

Which he will.

To say he got the book you ordered him, and

he hopes you’re doing well, and

22pray for him

because it’s gonna be a long

hard read.

Hidden Oaks Apartment, Sophomore Year

23Remember that first time smoking cigarettes indoors,

how it was morning birds outside the blinds and

spread thin in piss-stain sleeping bags you

pricked cracks in the wobbling wall

with your eyes, and, traced veins on your arms

with the pads of your thumbs,

how each and every way you turned

there was another burn

spinning webs behind your ribs, mamas looking down

from heaven’s curfew room sighing

Not another.

Send a guardian.

24Four to a room, you watched rotoscope cartoons, twitching

the cherry of your cigarette onto the peppered carpet, how you

rebuilt the hole burned in your brain

with orange juice and the feeling that you would always

need another cold shower,

looked left to find the tattered futon sagging

under two inert torsos, emaciated

children animated

by a sequence of shuttered eyelids, how you called it

or would call it home.

25Pull a single brick, the structure crumbles.

Pull the star,

four blind mice for whom communion is nothing more

than blood and needles,

or the ecstasy pill that says I love you

so long as the sun hides his molten smile.

Remember how you were trained

within that smile and that, though birds may sing,

morning is only the aftersong of sunset

for whom the night will rise.

Remember how this, and love too,

will destroy you.

Puppylove

261.

I was nineteen

staring at a screen

of a reflection of a reflection.

It makes me see what I want to see

and be what I want to be.

272.

It doesn’t hurt

but see how deep the bullet lies.

Fold down your hands

and turn down the light.

283.

Now you’ve absorbed it into your system:

a whole entire garden—

more than random flowers

bursting from my mouth.

294.

Let’s exchange the experience:

I will play tender with you

30will scatter on the floor

run through the moss on high heels

waiting for a moment to arise.

315.

In time when it crashes

I’ll eat the paint off.

326.

Empty vessels ring true

like bells

make the most noise.

33To you

I am a singer at the bottom of the well

disappointed and sore.

Write a Poem With Me

348 October 2016, Facebook

35I (verb phrase) (noun) (verb phrase),

and I didn’t have a gun.

36I was shot by the cops with my hands up,

and I didn’t have a gun.

37Took your sorrow to make my own,

and I didn’t have a gun.

38Woke up in the body of my only enemy,

and I didn’t have a gun.

39I was informed there was no treatment,

and I didn’t have a gun.

40I wanted them to cry my name,

and I didn’t have a gun.

41I watched Donald Trump debate Clinton,

and I didn’t have a gun.

Letter to a Future Lover

42Dusty winds may exist.

Dangerous winds.

Dust storms may exist.

43Zero visibility possible.

Do not stop in travel lanes.

Use extreme caution.

44Silver City: Think Wilderness.

Slower traffic keep right.

Silver City: Think

45Colorful. Care

For your loved one,

Care for yourself. Use

46Extreme caution.

Continental divide

fireworks. Roadwork

47Next 10 miles. Left lane.

Left lane closed.

Pedestrians prohibited.

48Dead end. Prison facilities

In this area; Notice:

Please do not pick up

49Hitchhikers. Lonesome Road.

Pedestrians. Missile range

Headquarters.

50After you die, you will meet

God. Put your money

where the miracles are.

Bird After the Snake, or 7 Opportunities to Fly

51As you were told, we unwound inside the viscous yellow membrane

of an egg the first day of [noun representing race] on quicksand,

52but never brutal, cawing as the crow

descends, just able to endure

its own dejected weight,

diving at our sinking scalps with scythes and sugar water.

53We laid the table with silk and splintered planks

for clawing after, gnawed the lid off of our cage,

invited them, the [noun representing bird of prey]

to the puddle into which we spilled at birth and stayed.

54They took our [noun representing something freely given] as a threat,

55[noun representing a home that is not a home, that is a prison, or a nest, adorned in time with bricolage]

trying to find the imaginary blade with which

56we would cut off their wings.

They supposed that we

would cut off their wings when really they were

after a meal, and we were of a feather.

Frankenstein’s Monster

57William Godwin’s black and red ink,

on the morning Mary Wollstonecraft

died of puerperal fever,

58records the date,

reads 20 minutes before 8,

and cuts the page:

59three thin lines making way

for the vast and irregular plains

of ice which seemed to have no end.

Feelin’ Like a Party Girl, Ooooohkay!: On the Nature of Language

60Poetry is a list of punctuation marks written

As a contract I make with myself

61Which says today my life will have meaning

Just for today

Order.

62For instance:

Something in the presence of who knows what the raid parade a party in the boulevards where women got their knickers tucked but caravans and piper clowns don’t pit you in the distance between lemonade and autumn gale licker split the forty o

63Did you feel it?

Did the moment in prose

In which I closed my eyes

Typed each word as it surfaced

In red calligraphy upon the backs of my eyelids

At random register in the deep of your marrow?

64Was it hollow as the bones?

Did it register inside that hollow

And make you miss the bones?

Did you miss believing?

The mind and marrow

65Seems to make sense but doesn’t,

Seems to have meaning but isn’t

Meaning isn’t anything other than seeming.

66Because prose is the shape of everything

Stuffed into a tube and shaken

It comes out that way.

67But when I sign a contract in verse—

Contract the filament pulp

Through straws pump the marrow

Through bone,

Its tight packed straws

I say

68Something

I say in the presence of someone

Someone who knows I say something

In the presence of someone who knows

What raid parade means

Even though I didn’t

burns like a caravan

69We call it a party

A party in the streets

A party in the streets and we call them boulevards

Because boulevards is French if I’m not mistaken

And culture is the place where women

Get their knickers and gowns

70It was a poem in pulp

But it could have been

A period.

Acknowledgments

71Thanks to Nimrod International Journal, UnLost Journal, and Permafrost Magazine, where versions of the following poems first appeared, respectively: “Whale Sounds,” “Letter to a Future Lover” and “Body Shape.” Deepest thanks also to Anne-Laure Tissut for the incredible opportunity to share these poems in Rouen.

Katz Daniel, “James Schuyler’s Epistolary Poetry: Things, Postcards, Ekphrasis”, Journal of Modern Literature, vol. 1, 2010, p. 143-160.

Perloff Marjorie, “A Response”, in Mark Jeffreys (dir.), New Definitions of Lyric: Theory, Technology, and Culture, New York, Garland Pub., 1998, p. 245-255.

Ce(tte) œuvre est mise à disposition selon les termes de la Licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas dUtilisation Commerciale - Partage dans les Mêmes Conditions 4.0 International. Polygraphiques - Collection numérique de l'ERIAC EA 4705

URL : https://publis-shs.univ-rouen.fr/eriac/762.html.

Quelques mots à propos de : Zach Linge

Florida State University

Zach Linge is a graduate student in English at the University of Texas at San Antonio, whose research interests include deconstruction, queer theory, modern and contemporary poetry, and the history of witchcraft. Zach was assistant to the editor on the forthcoming Understanding Foucault, Understanding Modernism (Bloomsbury Press); contributed a chapter on the late Serbian-American poet Charles Simic to the forthcoming Anthology of American Authors (Ed. Steven Kellman; Grey House Publishing and Salem Press); and has published poems in Nimrod International Journal, and Permafrost Magazine, among others.