Sommaire

4 | 2018

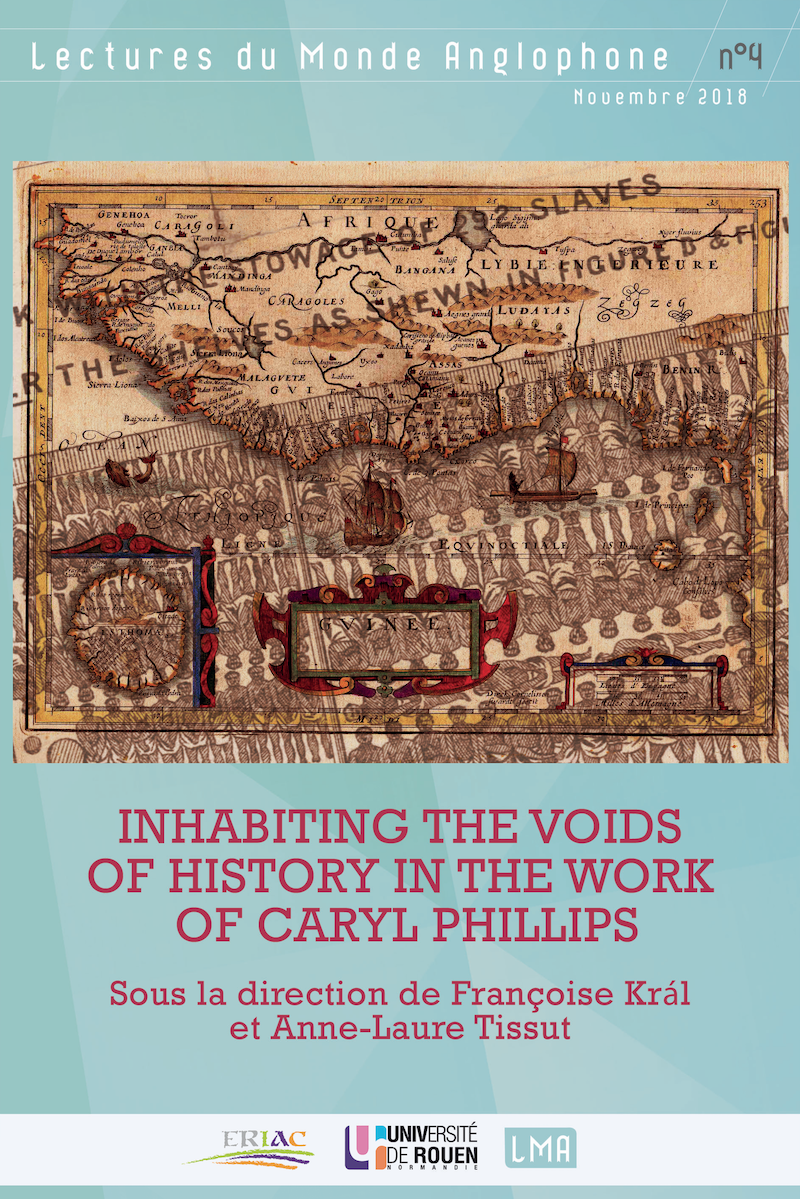

Inhabiting the Voids of History in the works of Caryl Phillips

The present volume proposes to re-read the work of Caryl Phillips through the prism of his engagement with history, both the history of the Middle Passage as well as the unread and unspoken history of lives which have not yet made it into official history. His work can be approached as an invitation to reflect on the role of literature and in particular on the specificity of the literary author with regards to the writing of history and the specificity inherent in handling historical material. More largely this question prompts another issue which is: where does history start, and where does it stop? In recent decades, the rise of subaltern history, women’s history and the histories of minorities has largely broadened the spectrum of what history is about. Absence and loss, mourning and the impossible return are key tropes which haunt the work of Caryl Phillips to the point that the aesthetics which he has crafted over the years seem to weave complex networks of narrative voices which circle voids that are constantly retold, and sounded out. This way of positing the void at the centre is all the more interesting as it constitutes an aesthetic shift from a choice often made in contemporary literature to represent the body, and in particular the wounded body, as a palimpsest of pain which bears witness to the sufferings of the 20th century subject, the post-modern subject and the post-colonial subject. Rather than engage with a thorough and graphic depiction of a suffering body, Caryl Phillips generates a voice which circulates along tangential lines of transmission and prompts the reader to receive and reactivate the salvaged narratives retrieved from archival oblivion. The present volume constitutes a reappraisal of the work of Caryl Phillips up to his most recent novel A View of the Empire at Sunset (2018).

- Françoise Král Introduction

- Kathie Birat Historicising Emotion in Crossing the River by Caryl Phillips

- Justine Baillie “There are no paths in water”: History, Memory and Narrative Form in Crossing the River (1993) and Foreigners: Three English Lives (2007)

- Françoise Clary Extending Intersectionality theory to the perception of Blackness and otherness in Phillipsian social space

- Josiane Ranguin “Happiness is not always fun”: Caryl Phillips’s Crossing the River, part IV (1993) and the BBC Radio Dramatization “Somewhere In England” (2016), Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s Ali: Fear Eats the Soul (1975) and Robert Colescott’s My Shadow (1977) and Knowledge of the past is the key to the Future, (St Sebastian) (1986).

- Giulia Mascoli Spectral Echoes in Caryl Phillips’s The Nature of Blood

- Maria Festa The Nature of Blood and Fragmented History

- C. Bruna Mancini Spaces of memory, identity, and narration in Crossing the River (1993) and A Distant Shore (2003)

- Max Farrar Radical dislocation, multiple identifications, and the subtle politics of hope in Caryl Phillips’s novels

4 | 2018

Extending Intersectionality theory to the perception of Blackness and otherness in Phillipsian social space

Françoise Clary

1This article’s contention is that the perception of blackness and otherness in Phillipsian social space is best understood by referring to what is most important about intersectionality theory, its insight that identities are a compound of overlapping elements. The essay focuses therefore on the dialectic established by the narrator of Crossing the River between a number of shifting levels of vision that reflect an acceptance of hierarchies of identity – then disclaim these hierarchies. The essay analyses more specifically, the way empowerment is to be understood as the key unmasking device, as evoked by Kimberle Crenshaw when she argues that the process of categorization is itself an exercise of power. The reader is thus invited to explore how each section of Crossing the River provides a motivational account of what is salient in a character and helps identify what is in correlation with the various categories of identity (such as race, class, gender, and culture) that meet to form a global, composite identity. The article also chooses to extend intersectionality theory to the perception of blackness and otherness in the collection of essays Colour me English, with the purpose of showing how race and class, or race and culture overlap, while pointing at their interaction that contributes to create additional forms of subordination. The paper finally considers how Caryl Phillips’ description of the “Other”, in Paul Ricœur’s term, functions as a distancing device used to challenge the incompleteness of traditional history.

2Any attempt to come to terms with the significance of the quest for self-realization and identity in literatures of colonial contact must begin by positioning the parameters of otherness. The problem with the subtle concept of otherness is not only that it draws on the strength of black writers’ shared experience in their struggle with cultural hegemony and the dismissive “othering” of blackness but that understanding otherness also implies understanding the external forces that have transformed the way we conceive of subordination. There is something unsettling in the notion that otherness is not merely a symbolic construct but the product of subordination, as Gayatri Spivak argues in “Can the Subaltern Speak?” (1998, 271-313). In such a mode of awareness, if emulating Robert Carr (2002) we question the constitution of the public sphere as forum in its history, identity, ethnicity, and class, we cannot fail to wonder whether the voice of the subaltern on whose domination society and the state are founded can ever be heard.

3Considering that patterns of subordination intersect, my objective in this article is to use intersectionality theory as theoretical framework in order to examine the interplay between such factors as race, gender, culture and class and find how their interaction may provide insights into a fuller understanding of the forms of oppression of the subordinated. This intersectional approach to social perception of systems of domination in Caryl Phillips’s essays collected in Colour me English, and his novel Crossing the River, can help fill in the gaps of incomplete histories of the black diaspora that are associated with dislocation and loss. Meanwhile, putting the focus on the intricate reciprocity formed by history and fiction can be of use in undermining the binary logic of historical parallels in the context of cultural studies and in offering new insights into the nature of the overlapping concerns of Caribbean and European modernism.

4It is Simon Gikandi’s contention that Caribbean modernism develops from an anxiety about the history, language, and ideology of colonialism (Gikandi, 1992). But while Gikandi is willing to use modernism as a critical concept, blackness is not presented as a discursive category – even though it impinges on all the other categories. Going beyond Gikandi’s binary distinction between Caribbean and European modernisms therefore implies putting the focus on how, in modernist literature, discourse is likely to be invaded by intertexts from different centers and to be open to intersectional analyses. This point could benefit from a dual focus on Phillips’s Colour me English and Crossing the River as these two books foreground a variety of discourses that reveal an ability to repattern historical material and blur the distinction between the actual and the possible. They also re-create a historical reality that challenges individual interpretations of otherness / blackness / identity / hybridity in which the migration of worlds and words helps to give voice to unspoken memories. My purpose, in this paper, is not only to question identity and otherness in Phillipsian social space but to trace one of the most profound aspects of Phillips’s writing, the expression of the impulse to survive trauma and dislocation because, for the novelist, imagining is indispensable to combat the voids of history.

Theoretical framework

5The question of how one should approach diasporic consciousness and conceive of the process of marginalization and ethnocentrism that is constitutive of the incomplete history of a traumatic past, is raised when turning to Critical Race Feminism’s intersectionality theory to analyze overlapping social identities and related systems of oppression. However surprising such an approach to the literature of colonial contact may seem, to adopt American civil rights advocate Kimberle Williams Crenshaw’s idea of intersectionality is appropriate to help us understand how multiple forms of identity can interact to create a whole including gender, race, social class, ethnicity, nationality, sexual orientation, religion, age, mental or physical disability, mental or physical illness.

6What Crenshaw’s intersectionality theory proposes is that each element or trait of a person should be considered as inextricably linked with a variety of social elements in order to grasp the true meaning of one's identity. Conclusions will therefore be drawn in this article from an analysis of the interplay between categories such as class, ability, gender, nation, or race because apprehending their interaction can lead to a better understanding of the silence in which history, home, and identity are shrouded for members of the African diaspora.

7In fact, three main points drew my attention to intersectionality theory, usually applied to the multiply subordinated such as women of color – reference being made to “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity, Politics, and Violence against Women of Color” (Crenshaw 1991, 1241-1299) and its insight that identities are always formed at the point where categories of identity meet. Indeed, Crenshaw holds that multiple grounds of identity operate all at once in any one individual. She further contends that people are all always raced, gendered, and sex-oriented. These three points, outlined by Frank Rudy Cooper in “Against Bipolar Black Masculinity: Intersectionality, Assimilation, Identity Performance, and Hierarchy” are: the scaling of bodies, bipolar black masculinity, and the desire for compensatory subordination. The first point, the scaling of bodies – identified by intersectionality theory as part of the shared roots of oppression – is the assumption that identity characteristics must be ranked against a norm and that society should be organized according to the hierarchies defined by the norm. The second point concerns the “bipolar images of black masculinity” (Cooper 2006, 874) that alternate between the “Bad Black man”, depicted as “crime-prone” and the “Good Black man” who distances himself from blackness and abides by white norms. The third point refers to the desire for compensatory subordination as associated with the claim for the right to subordinate others as compensation for one’s own subordination.

8Observing, as Cooper does, that “intersectional analyses are usually applied to the multiply subordinated” (Cooper 856), one recognizes in otherness and blackness elements that are a source of subordination since these two concepts are related to the various ways in which race and ethnocentrism interact. In fact, the words “otherness” and “blackness” share a modern legacy as evaluative terms. In the context of literature of colonial contact, otherness may be codified as a cultural construct produced by the discontinuities of colonial encounter and grounded in the traces of slavery, colonialism, and ethnic admixture that engage peoples of the African and Caribbean diaspora through a differential cultural dialogism: How is the word “culture” to be understood? Is it to be confined to the concept of cultural estrangement, including the ordinary biases of identity preference? Or is it to be extended to sets of partially overlapping ideas since, in terms of identity, the most important aspects of the geographical relation are cultural and social?

9I will argue here that blackness constitutes another aspect of the central debate that has developed within the context of academically produced discursive practices. If we look for a linguistic self-definition of blackness in the field of African American fiction through a brief focus on Richard Wright and James Baldwin’s aesthetic concerns, we may oppose Wright’s discursive praxis to James Baldwin’s. Emanating from a binary conceptualization of blackness in contradistinction to whiteness, Wright depicts a fragmented black self, psychologically maimed by racism, in Native Son’s protest discourse. By contrast, Baldwin conceptualizes a different type of blackness, and so does Ernest Gaines. For Baldwin, as for Gaines, blackness is to be equated with the empowering effect of immersing oneself in the shared space of black life that is in the history of the diaspora with the impulse to survive trauma.

10Theoretically speaking then, while the interdiscursive relationship between black and white subjects is not new, blackness is characterized as “Afrocentric”, “African‑centered”, “essentialist” on the one hand, but as ‘hybrid’ on the other. Thus, in African-centered discourse, the term “culture” is associated with an imperative toward cultural cohesion whereas “hybrid” discourses tend to emphasize the incomplete nature of all identities. Drawing on Stuart Hall’s 1992 essay “What is this ‘Black’ in Black popular culture?” in which Hall evokes disparagingly “European models of high culture” (Hall 1992, 21), Paul Gilroy contends in The Black Atlantic: “The ontological essentialist view has often been characterized by a brute pan-Africanism. It has proved unable to specify precisely where the highly prized but doggedly evasive essence of Black artistic and political sensibility is currently located, but that is no obstacle to its popular circulation” (Gilroy 1993, 31). Hence my objective to observe the interplay of factors that have led to African American marginalization because they are at the core of the sociopolitical or cultural construction and bear on patterns of subordination.

Identity and Culture

11James Clifford questions the concept of cultural identity and therefore the very notion of otherness, most particularly when he asks the following two questions: “Who has the authority to speak for a group’s identity or authenticity? What are the essential elements and boundaries of a culture?” (Clifford 1998, 7-8). Phillips, for his part, responds to the questioning of the structures of identity by conceiving of the politics of otherness as anything but closed. His approach seems to capture some sort of essence to “contact culture” that can be rightly instantiated in establishing a link between Colour me English and Crossing the River.

12Indeed, in terms of identity the most important aspects of the geographical relations Phillips is concerned with are cultural and social. But what is of greater interest is that in his approach to blackness and otherness, the author is not satisfied with letting his reader imagine discrete systems of oppression. He aims to demonstrate that hierarchy is neither natural nor inevitable, and that race, class, gender, and culture interact, as exemplified in Colour me English or Crossing the River. The intersection of race and culture is thus made obvious in the introductory essay “Colour me English” when the narratorial focus switches to the identity-based othering of Ali, the Muslim newcomer, bullied by the schoolboys of Leeds Central High School. Meanwhile, it is the history of the scaling of bodies, relying on the assumption that identity characteristics must be ranked against a western, white norm that comes up to the surface in the section “Crossing the River”. There, the notes written down in Captain Hamilton’s Journal give precise information about the slaves’ size, health, and physical appearance. The ranking of bodies is also addressed most vividly in the auction scene in “West”.

13What is the strongest rationale for linking up legal intersectionality theory with literature? First developed in “Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics” (1989), the intersectional approach is used by Crenshaw to analyze how “the intersections of race and gender highlight the need to account for multiple grounds of identity when considering how the social world is constructed” (Crenshaw 1991, 1245). Now, observing the interplay of various forms of social identities by bridging Colour me English and Crossing the River offers an approach to the new kinds of critical attention Phillips focuses on overlapping social identities and related systems of oppression. In this spirit, implicit in such an approach is the assumption that the novelist is also concerned with the structures of identity within societies whose oppressive institutions, such as racism, sexism, ageism, or appropriation of the sociocultural discourse do not act independently, but interact to create a social hierarchy.

14“[…] women of color can be erased by the strategic silences of antiracism and feminism” Crenshaw argues (Crenshaw 1991, 1253). Supposing we extend this remark to the black diaspora, could we not claim that parts of its history have been erased by silences? Crenshaw holds that legal theorists must consider how intersections of race, class and gender affect both laws and political movements, and the social space too: “Race, gender, and other identity categories are most often treated in mainstream liberal discourse as vestiges of bias or domination – that is, as intrinsically negative frameworks in which social power works to exclude or marginalize those who are different. According to this understanding, our liberatory objective should be to empty such categories of any social significance” (Crenshaw 1993, 1242). Within the terms of the symbolic universe of fiction, how does Phillips negotiate and critique constructions of identity?

15My contention is first that the novelist’s perception of blackness and otherness is best understood by referring to what is most important about intersectionality theory: its insight that identities are a compound of overlapping elements. What is to be noted, in this respect, is the dialectic established by the narrator of Crossing the River between a number of shifting levels of vision that, at times, reflect an acceptance of hierarchies of identity – as illustrated in the first letters from Nash to Edward Williams in “The Pagan Coast” – then disclaim these hierarchies as Madison does theatrically when he walks away from his former master, ignoring him. The key unmasking device is empowerment, as evoked by Crenshaw: “The process of categorization is itself an exercise of power” (Crenshaw 1991, 1297). In fact, each section of Crossing the River provides a motivational account of the correlation that identifies what is salient in a character with the various categories of identity (such as race, class, gender, culture) that meet to form a global, composite identity. Crenshaw’s argument, as mentioned above, that people are all always raced, gendered, sex-oriented can be grasped in the framework of the narratives imagined by Phillips to explain how injustice and inequality intersect on a multidimensional basis. Hierarchy is not an immutable characteristic insists the novelist as he leads the reader to understand that when one thinks of hierarchy one has to imagine systems of psycho-cultural alienation.

16Thus, if we choose first to extend intersectionality theory to the perception of blackness and otherness in the essay “Colour me English”, we notice that two systems overlap – race and class, and also race and culture. Their interaction contributes to create additional forms of oppression. Indeed, from the start, the reader is made aware of the difficulty for Britano-Caribbean schoolchildren to face a society divided in many ways – white versus black, upper class versus working class, elite versus subaltern – and these divisions, as outlined in Phillips’s narration, have come to define the ways in which class intersects with the perception of blackness whose meaning varies with the social context. Indeed, in Colour me English the context is first that of a working class district in an industrial town center in which blackness is to be understood as an unstable complex of social meanings: “We had been the only black children at our primary school, and we remained the only black family on a tough, all-white working class estate” (Phillips 2011, 3). Besides, the social positioning in which race and class intersect is continuously shaped by another, systematically antagonistic type of positioning tied to various modes of oppression. In like manner, it is the overlapping of race, class and ethnocentrism that has a bearing on the matter of whose voice can be heard and accounts for the domination that one social group (made up of the white schoolboys of Leeds Central High School) wishes to exert over outsiders. This mode of oppression involves categories of differentiation (with a major focus on blackness) that interact to create a social hierarchy. It is illustrated, most interestingly, by the rough behavior Caryl and his brothers had to adopt to survive: “All three of us were able to cope. We knew when to fight and when to run. In fact, most of my childhood was spent either fighting or running” (3).

17The interdependency of opposites is given symbolic realism once the reader is faced with the sociocultural restructuring of the concept of blackness. When we look more closely at the underlying logic of the text, what surfaces is that discrimination founded on the interaction of race and class is open to change if it is counterbalanced by social empowerment. This move is exemplified in the text by the reference made to the highly publicized, and therefore huge economic success of black sportsmen. The attention that is drawn to the intersection of race and class reflects a changing relationship to the African diaspora in Britain whenever the narrator evokes black people’s social empowerment. The concept of race is thus shown to be shaped by the transformation of the international perception of blackness as it is associated no longer with immigrants but with black athletes and sportsmen that are an asset for the country they live in: “The truth is, I did not want to be white, I just wanted to fit in, and I believed that colour was the issue. And then slowly things began to change. In November 1978, Viv Anderson, the Nottingham Forest fullback, became the first black footballer to play for England. Within a few years there were black players on most of the first-division football teams, and then there were other black faces in the English national team; soon after there were many black athletes on the Olympic track and field team, and black people on television reading the news. We were colouring England” (11-12). This passage from Colour me English draws its full significance from Crenshaw’s analysis of how systems of race and class domination intersect, and most particularly from the focus put on social empowerment as a way to oppose discrimination: “the social power in delineating difference need not be the power of domination; it can instead be the source of social empowerment and reconstruction” (Crenshaw 1991, 1242).

18In like manner, race, class, and also religion definitely intersect in the memories Phillips revisits to mind in “American Tribalism” where he evokes the lot of minorities in Britain and the system of domination that affects coloured people: “Minorities, be they religious or racial, have always encountered difficulties as they struggle to adjust to the vagaries of British life. As a young black boy, and a northerner at that, the double yoke of race and class was slipped firmly round my neck. I spent a great deal of my time as an adolescent being the only ‘different’ face in the room, and this did not change on going to university, particularly as that university happened to be Oxford” (29). There is a social and systemic dimension to the marginalization of members of the Black diaspora that is best understood by adopting the methodology of mapping the intersections of race and class; a concept, Crenshaw contends, that “can and should be expanded by factoring in issues such as class, sexual orientation, age and color” (Crenshaw 1991, 1245).

19In fact, a functional interdependency may be found in Phillips’s works. Each level of sociological perception flows into a dialectically higher level. For example, as far as the representation of people of color is concerned, the specific mechanisms by which African natives are marginalized in “The Pagan Coast” and “Crossing the River” are to be understood in terms of the interplay of race, class, religion and culture contained by a “higher level”. The latter is socially determined by forms of oppression that are interconnected, as shown by the varying types of domination that are at the core of the capitalist and colonial imagery of slave owners.

20These representations are basically the product of the intersection of race and class since capitalism grows out of colonialism as exemplified by the notes in the Journal of Captain Hamilton whose sole concern is profit-making. But it is necessary to go further and look for the hidden influence of culture and religion that cause some race/religion subgroups to face particular discrimination from the white hierarchy. To illustrate this point, we can refer to the description of the assault, Ali, the Southeast Asian newcomer is victim of when the bullies of Leeds Central High School grab his haversack and throw all of the young Muslim immigrant’s books one by one out of the speeding bus. The narrator makes it clear that not only do race and class intersect but that Southeast immigrants experience a form of discrimination that is peculiar to their history. The otherness they represent is associated with their social position: “I saw terror on Ali’s face and immediately understood that he could not afford to be frivolous when it came to the practical aspects of getting on in England as a non-white child” (5). A remark can also be made about the mutual implication of apparently exclusive concepts, as specific stereotypes about the “Muslim Other” assign the Southeast schoolboy to the cliché of the “marginal one” allowing the reader to see unexpected commonalities between immigrants.

21While stereotyping impacts the essay “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses”, a most interesting dual expression explains why non-white Others’ position in social hierarchies creates experiences of identity loss. Indeed, after achieving a brief historical survey of United States’ immigration policy in the first pages of this essay, Phillips chooses a multidimensional approach to the chronological evolution of the hostility shown to outsiders in the United States. It is related first to “their perceived exoticism and ‘difference’” (40), then to their ethnicity (“ethnicity began to play a larger role in national identity as strangers from many lands sought to gain admission into the American family” (40), including the reactions of US government and citizens to the danger outsiders may represent because of their cultural background, as the novelist specifies: “After September 11, […] immigrants from the Arab and Muslim worlds, many of whom might, in normal circumstances, have been considered transitional in today’s United States now find themselves trapped at the bottom of the pile, and below blacks” (40).

22Conclusions can be drawn from the process of recognizing the overlapping of identities as a meaningful element in a sociological logic of thought: It is easy to notice that juxtaposing real selves and false masks, the author makes use of the posture of cultural and religious identities intersecting racial identities in order to point out the hierarchization of individuals. For instance, by drawing attention to the scaling of ethnic groups in “The Pagan Coast” and “Crossing the river” Phillips shows that identity characteristics are ranking against a national and political norm that contributes to organize society according to hierarchies. This is also intimated in “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses” by a remark about the “profiling of an entire ethnic and religious group [that] has had repercussions for the police” (43).

23After drawing the basic contours of intersectionality theory and its application to the singly or multiply subordinated that are represented in Colour me English, one should emphasize the sense of the relationship of the present to the past that prevails when bridging the collection of essays Colour me English and the work of fiction Crossing the River. In fact, the shared interests of the singly and the multiply subordinated in defeating the Western epistemological system of the scaling of bodies demonstrates the survival of the past within the present as Paul Ricœur contends in The Reality of the Historical Past (Ricœur 1984, 11). In other words, the remark made in “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses” about a process of identity hierarchy and upward mobility that “confirms the existence of a racially discriminatory system which effectively keeps blacks pegged to the bottom rung of the socio-economic ladder”, (40) serves to symbolize the trace of a violent past whose horror cannot be adequately rendered in language. That is why the past that remains untold is left for the reader to reconstruct from the notes jotted down in Captain James Hamilton’s Journal in Crossing the River.

24In like manner, the novelist points at the unspoken history of the scaling of bodies, illustrated as follows: “Thursday 4th February This morning at daybreak I was saluted by the agreeable vision of my longboat, and soon after she came on board with crew well and a dozen slaves, viz., 4 men, 2 women, 1 man-boy, 1 boy (4 feet) and 4 girls (under-size)” (111). Or “Saturday 13th March… At noon the canoes once again on board, brought 8 slaves, viz., 2 men, 1 woman, 2 boys, 3 girls. All small, the girl slaves all below 4 feet” (113). Unmistakably, the details that are given in Captain Hamilton’s Journal concerning the scaling of slaves’ bodies comes close to the “mute testimony to forgotten histories” Maud Ellman refers to in “The Power to Tell: Rape, Race and Writing in Afro-American Women’s Fiction” (Ellman 1999, 46).

25It is necessary to go further because hierarchizing bodies is the corner stone of the philosophy of intersectionality theory. Unmistakably, the scaling of bodies is an assumption found within the core of Western Enlightenment thought. In 19th century western ideology, not only were white bodies presumed to be the ideal but Whites were considered to be intellectually, aesthetically, and morally superior to other people. This view is reflected in the romantic letters sent to his beloved wife by enamored Captain James Hamilton, so unfeeling when writing notes about the slaves he purchases and yet so humble and respectful when addressing his wife (“you, by marriage to one such as I, have exposed yourself to anxieties to which you were a stranger”, 109). For the captain of the slave ship, his wife, set up as the symbol of the white woman’s moral superiority, definitely ranks high in the social hierarchy, far above the wretched victims of the slave trade referred to as “petty concern” (“These are, indeed, petty concerns when set against my love for you”, 108).

26As the ideas of the intellectual, aesthetic, and moral superiority of white people have been raised to the level of philosophy, they have endowed the aesthetic scaling of bodies with the authority of objective truth, says Iris Marion Young. Identifying Western epistemological system of hierarchizing identities against norm, Young argues that “all bodies can be located on a single scale whose apex is the strong and beautiful [White, Christian male] youth and whose nadir is the degenerate” (Young 1990, 126). The creation of this scaling of bodies, Young concludes, means that people of color, non-Christians, and women, the old and other non-normative groups are deemed to be marginalized. Interestingly, this is hinted at in “West” when the colored pioneers heading for California part with Martha who confides: “They took upon themselves this old, colored woman, and chose not to put her down like a useless load. Until now” (92).

27Such a mode of perception remains in dialectical tension. The hierarchization of identities is pointed to both in Colour me English and Crossing the River. Not only is subordination shown to be based on race, class, gender and culture but the relationship that intersectional analysis establishes between the present and the past contributes to reconstruct the reality of a historical past. For instance, the othering of non-Christian schoolboy Ali, severely bullied in Leeds Central High School, or the marginalization of Southeast immigrants evoked in Colour me English, represent an aspect of reality that contains the trace of history. Indeed, the process of marginalization of the “Other” for his religion and his culture is open to rememorizing. This occurs in “The Pagan Coast” with the release of the story of the American Colonization Society in Liberia and its program of Christianization of African natives referred to as ‘heathens’ and consequently subordinated. Meanwhile, the introduction devoted to Nash Williams focuses significantly on the bipolar images of black masculinity with the distinction between “the Bad Black man”, African natives that “can be very savage” (32), and “the Good Black man”, the African American educator extolled for having undergone a rigorous program of Christian education.

The intersectional aspects of subordination

28The scaling of bodies creates a normative status within each identity category and ranks others against that norm. As a consequence, it renders invisible everyday norms that subordinate people with certain identities. Thus, whiteness can be the baseline because “to be white is not to think about it”, argues Barbara Flagg in “White Race Consciousness and the Requirement of Discriminatory Intent” (1993, 953-1017). If we accept her argument that all people in the United States recognize race but that whites often view their own racial identity as immaterial, then the racial norm is felt to be unidirectional. This is indeed what we are made to perceive in “Somewhere in England” when reading the U.S. officer’s statement about African American soldiers as reported by the narrator: “Today an officer came into the shop wearing dark glasses. […] I’ve come to talk to you a little about the service men we’ve got stationed in your village. […] A lot of these boys are not used to us treating them as equals, so don’t be alarmed by their response. […] It’s just that they’re different” (145). Extending the intersectional perspective to the narrator’s approach to blackness, we are faced with an opposition between the white U.S. officer who represses his racial identity into subconscious, but not the significance of African American soldiers’ racial identity. Meanwhile racial minorities cannot afford to ignore the impact of their own racial identity, as illustrated by the confrontation of Trevor with the military police or else by the officer’s remark when coming into Joyce’s shop: “A lot of these boys are not used to us treating them as equals, so don’t be alarmed by their response” (145). From the interpretative viewpoint, blackness is associated with subordinated minorities in mainstream liberal discourse.

29I will now extend Cooper’s view of the bipolar representation of black masculinity to an analysis of the intersectional aspects of subordination in Phillips’s text with a focus on the predominant images of black men sketched out in “‘O’. All alone in Charleston” from Colour me English and in “The Pagan Coast” from Crossing the River, drawing first from legal scholar N. Jeremi Duru’s article The Central Park Five, the Scottsboro Boys and the Myth of the Bestial Black Man that schematizes some of the key components of the ‘Bad Black man’ image. That figure is based on three assumptions: first, black men are animalistic; second, black men are inherently criminal, and third, black men are sexually unrestrained. In contradistinction, the “Good Black man” is supposed to distance himself from black people and assimilate into white culture by emulating white norms.

30Actually, race, class, gender, and culture discourses combine to create a particular narrative. Thus, in the essay “‘O’. All alone in Charleston”, an imaginative interpretation of Tim Blake Nelson’s film “O” (2001) that attempts to update Shakespeare’s Othello to the contemporary world of Charleston, South Carolina gives life and meaning to the stereotype of the “Bad Black man” through the untold experiences of “O”, Othello “reborn as Odin James, high school basketball star”. Not surprisingly, refusing the national amnesia surrounding the history of slavery and discrimination, Phillips comes to terms with the negative stereotypes of the “animal-like” black man that resurrect racist ideology when he recounts his translation of Nelson’s film: “Our modern-day African American Othello is initially a grinning wonder-child […] However, the slightest provocation from one of the white boys soon kindles an anger that returns Odin to his ‘natural’ condition. His best friend Mike puts it pithily: ’the nigger’s out of control’. For the avoidance of doubt he continues: ‘the ghetto just popped out of him.’” (89-90). To be more specific, in Nelson’s film, the interiority of memory of racism is brought to the surface by the configuration of the image of the black rapist, and the urban beast.

31To some extent, the timeless and placeless Othello reborn in Odin James of Charleston is the “Other”, in Paul Ricoeur’s term. The image of the “Bad Black man” that is conveyed in Phillips’s translation of Nelson’s film functions as a distancing device. As a consequence, individual and cultural histories are rememorized.

32A similar distancing device can be observed in “The Pagan Coast”. The African natives are described not only as culturally different, as “heathens”, but they distinguish themselves by “their crude vulgarity sometimes taking the form of aggression” (8). Their being described as crime-bent (“native attacks resulted in a heavy toll of life”, 9) exemplifies the link established in Western epistemology between blackness and criminality, all the more so as those among the emigrants who are lazy or commit thefts are said to be acting like the African natives (“Those who don’t work and who get along by stealing are becoming something like the natives”, 18). We also note that even when the African native’s work deserves some praise, he is mainly described as a “body” and a simple-minded, or childish being (“The natives worked with glee” 23; “They are good workers, although they require a stern and watchful supervision”, 27).

33In contrast, the position occupied by Nash Williams is in keeping with the representation of the ‘Good Black man’. In other words, as an educator and a missionary, Nash Williams is an image of the paradigmatic black man against whom many whites measure other blacks. Specifically, as long as he educates and Christianizes natives, Nash upholds representations that condition black males to embrace subordination as ‘natural’ while contributing to construct a worldview where white men are depicted as all powerful. If we pay attention to the letters Nash wrote to his surrogate father, more particularly to the one dated September 11th, 1834, it is clear that his standing by western hierarchies tends to set up normative white men as the model.

34Why be concerned with bipolar images of blackness? Because binary popular representations promote different types of behavior. Their being used by African American emigrants for marginalizing African natives in “The Pagan Coast” reinforces the idea that identity characteristics can be a basis for subordination. Indeed, one of the reasons why, in “The Pagan Coast”, African American emigrants themselves adopt this bipolar representation associating the African native with the image of the heathen, uncivilized “Bad Black man” is that it seduces them into occupying a high rank in western hierarchies. By looking down on African natives, African American emigrants emulate the economically-empowered white men who set the norms in a culture whose epistemological foundation is the assumption that there must be a hierarchical ordering of people based on their identities.

35Carrying on an intersectional approach to “The Pagan Coast” in keeping with Cooper’s perspective, we can point out the bipolar images of blackness that structure an underlying process of compensatory subordination in the text. African American emigrants, who, as former slaves deported to West Africa are actually in the position of the multiply subordinated, seek to offset their feelings of powerlessness by subordinating others, namely the African natives. Emulating normative white men means emulating a version of a culture that is based on the dominance of those below you in the identity hierarchies.

36The concept of compensatory subordination, Crenshaw argues, captures the idea that people who are subordinated may seek to compensate themselves for their own oppression by subordinating others. By doing so, Crenshaw contends, they accept the principles that identities should be hierarchized and consequently weaken their ability to reject the legitimacy of their own oppression. Now, if African Americans’ desire to subordinate African natives is made clear in “The Pagan Coast”, we also notice, as Intersectionality theorists have pointed out, that black male acceptance of hierarchy takes the form of subordination of black women through physical and symbolic abuse. In a sense, it is not surprising to observe, in the section “West”, that black male pioneers of the West achieve masculinity at the expense of black women, as illustrated by Martha’s laundry chores. Interestingly, the narrator insists on the painfulness of the washing of the pioneers’ clothes Martha has to do repeatedly in a short descriptive passage combining the painfulness of heat and physical tiredness (“I lift the dripping pile of clothes out of the boiler and drop them into the tub[…] I am hot. I wipe my brow with the sleeve of my dress, and then again I bend over and try to squeeze more water from the shirts. […] I continue to knead the clothes between my tired fingers” 83).

37It is hard to talk about something as abstract and pervasive as hierarchy but it is necessary to mention it. Intersectionality theory explains that systems of oppression are interlocking. Thus, when we bridge two statements made by Martha about her march westward with a group of colored pioneers: “I nursed and fed many of them through the first trying days, forcing food and water down their throats, and rallying them to their feet in order that they might trudge ten more miles towards their beloved California” (93), and: “Old woman. They had set her down and continued to California” (73). We cannot fail to take account of the undercurrent of ageism, which is particularly charged with significance in a context of patriarchal hierarchy, even though Martha’s story obviously has a self-interested component: not to slow down the progress of the wagons to California.

Reconnecting to the past

38Given the intersectional approach taking into account the scaling of bodies, the bipolarity of the black man and compensatory subordination, the result of reading “The Pagan Coast” is the hidden relationships between opposites, or oppositions within apparent unities since African American emigrants promote the naturalization of hierarchy through a radical segregation of African natives. The latter are positioned at the bottom of the social ladder while the African American immigrants promote assimilation according to the white man’s norm; which implies that they have reconstructed a hierarchy in the first place.

39The intersectional perspective on “The Pagan Coast”, where the former Black slaves from America sent as “colonizers” to Liberia take pleasure in emulating whites, highlights a two-step process, with, on the one hand, the intersection of the bipolar images of black masculinity that encourage black men to engage in race-emulating strategies and make the hierarchy of identities seem inevitable. But on the other hand, the last pages of the “Pagan Coast” disclose the hidden effect of the bipolarity of black masculinity that brings about new definitions of blackness in opposition to a set of mainstream values. The reason for this new perspective is that, simultaneously, an evolution is underway as Nash’s letters to his surrogate father and former master remain unanswered. Not only do we witness Nash Williams – symbolizing the ‘Good Black man’ – challenge black men’s place in the hierarchy by pitting the black woman’s image against the white woman’s, but Nash glorifies the image of Africa in a realistic revival of the physical presence of the historical past. Then the constant presence of the historical past predominates. When Nash announces his final decision to move away from the white American culture he was raised in and turn back to the traditions of his African ancestors, his words are made all the more meaningful because of the various allusions to his having several wives and children. This shift to African traditions is presented as the final step in the black hero’s escape from white society’s cultural indenture.

40In analyzing the types of behavior Edward Williams’ bipolar representation of the black man promotes once he has reached the place where Nash lived before his demise, we can identify, through his shock at witnessing what are for him “scenes of squalor” of a “primitive nature” (66) the same kind of distancing from Africa that Chinua Achebe claims was Joseph Conrad’s. Indeed, in his essay “Chinua Achebe. Out of Africa” from Colour me English, Phillips reports Achebe’s standpoint in these terms: “Achebe’s lecture quickly establishes his belief that Conrad deliberately sets Africa up as ‘the other world’ […] ‘the antithesis of Europe and therefore of civilization, a place where man’s vaunted intelligence and refinement are finally mocked by triumphant bestiality’” (198). The dichotomy between Nash’s environment (said to be ‘primitive’) and Nash himself (the black teacher who was supposed to emulate the white norms) is a false one. It limits Edward’s ability to see that the system of hierarchy he believes in and the cultural indenture he wishes to impose on Nash’s children by taking them forcibly to America, that is to say to ‘civilization’, is wrong.

41Undeniably, the sense of the relationship of the present to the past provides a link between Crossing the River (1993) and Phillips’s essay “Ghana: Border Crossings” (2004) where we, readers, are haunted by these sentences: “No African wanted to leave Africa. None. Including myself. […] My sympathies are located on the west coast of Africa. […] Diasporan Africans are a long-memoried people” (309-310). In “The Pagan Coast”, the final image of the black man is no longer that of a man who endeavors to emulate whites and desires compensatory subordination. It is the image of a man who claims proudly: “I therefore freely choose to live the life of an African” (62) and says: “We, the colored man, have been oppressed long enough. We need to contend for our rights, stand our ground, and feel the love of liberty that can never be found in your America” (61). What is to be noted, at the end of the story, is that the author proceeds to a complete deconstruction of the system of hierarchy in a graphic and highly symbolical scene in which the positions are reversed: African natives are looking down with pity on Nash’s former master who is now but a senseless old white man. We may suppose that it means that the black man can resist the seduction into hierarchy. But the deep significance of the reversal of the system of hierarchy is more complex than the rejection of subordination. By laying emphasis on the deconstruction of white supremacy, norms and culture and acknowledging Africa as a site of memory, the author proceeds to a decentering of the white logos. We can’t go as far as argue that it might imply the choice of essentialism. But why not borrow from Timothy Powell the concept of “black logos” (Powell 1990, 747) to identify blackness?

42It can’t be denied that the structure of “The Pagan Coast” raises the question of a possible decentering of the white logos for a re-centering of the Self of the black protagonist on Africa while rejecting his experience in America. Undoubtedly, the decentering of the white logos to rebuild the center with a black logos may attract our attention, but logocentric claims have to be discarded because, as Henry Louis Gates contends in Figures in Black they form the basis of a concept of essential differences among people. Now, that type of approach is foreign to Phillips’s view of Diasporan quest.

43The idea that all knowledge is symbolic construction brings with it the possibility of developing several forms of explanation. I will therefore conclude with this quote from Kwame Anthony Appiah who points out that while race “plays a central role in our thinking about who we are, in structuring our values, in determining the identities through which we live, the ideas that races are essentially different is a Victorian construct” (Appiah 1990, 275). Appiah’s remark echoes beautifully this emotional passage from Colour me English, in which Phillips’s aesthetic and sociological approach to the African diaspora offers perspectival knowledge fit to fill in the voids of history: “In the case of the African diaspora, the combined legacy of the Harlem Renaissance is worth nothing when balanced against the anguish of one single African in a dungeon deep in the bowels of Elmina Castle, chained to a now dead and putrefying friend, their mind racked with terror at the thought of what may lie ahead” (310).

Appiah Kwame Anthony, “Race”, in Franck Lentricchia & Thomas McLaughlin (ed.), Critical Terms for Literary Study, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1989. 274-87.

Carr Robert, Black Nationalism in the New World: Reading the African American and West Indian Experience [2002]. Durham, Duke University Press, 2002.

Clifford James, The Predicament of Culture. Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1998.

Cooper Frank Rudy, “Against Bipolar Black Masculinity: Intersectionality, Assimilation, Identity Performance, and Hierarchy”, UC Davis Law Review, vol. 39, 2006, p. 853-906.

Crenshaw Kimberle, “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics”, University of Chicago Legal Forum, vol. 1, 1989, p. 1241-1299.

Crenshaw Kimberle, “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity, Politics, and Violence against Women of Color”, Stanford Law Review, no 6, 07/1991, p. 1241-1299.

Duru N. Jeremi, “The Central Park Five, the Scottsboro Boys, and the Myth of the Bestial Black Man” Cardozo Law Review, vol. 25, 2004, p. 1315-1340.

Ellmann Maud, “The Power to Tell: Rape, Race and Writing in Afro-American Women’s Fiction”, An Introduction to Contemporary Fiction: International Writing in English Since 1970, Rod Mengham (ed.), Cambridge, Polity Press, 1999.

Flagg Barbara, “‘Was blind but now I see’: White race consciousness and the requirement of discriminatory intent”, Michigan Law Review, vol. 91, no 5, 03/1995, 953-1017.

Gates Henry Louis Jr., Figures in Black [1987], New York, Oxford United Press, 1987.

Gikandi Simon, Writing in Limbo: Modernism and Caribbean Literature [1992], Ithaca, Cornell University Press, 1992.

Gilroy Paul, The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness [1993], Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1993.

Hall Stuart, “What is this ‘Black’ in Black popular culture?” in Gina Dent (ed.), Black Popular Culture, Seattle, Bay Press, 1992.

Phillips Caryl, Crossing the River [1993]. London, Vintage, 2006.

Phillips Caryl, Colour me English, Selected Essays [2011], London: Harvill Secker, 2011.

Powell Timothy B., “Toni Morrison: The Struggle to Depict the Black Figure on the White Page”, Black American Literary Forum, vol. 24, 1990, p. 747-60.

Ricœur Paul, The Reality of the Historical Past [1984], Milwaukee, Marquette University Press, 1984.

Spivak Gayatri, “Can the Subaltern Speak?” in Cary Nelson and Lawrence Grossberg (ed.), Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture, Urbana, University of Illinois Press, 1998, p. 271-313.

Young Iris, Justice and the politics of difference [1990], Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1990.

Ce(tte) œuvre est mise à disposition selon les termes de la Licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas dUtilisation Commerciale - Partage dans les Mêmes Conditions 4.0 International. Polygraphiques - Collection numérique de l'ERIAC EA 4705

URL : https://publis-shs.univ-rouen.fr/eriac/434.html.

Quelques mots à propos de : Françoise Clary

Normandie Univ, UNIROUEN, ERIAC, 76000 Rouen, France

Françoise Clary is Professor emeritus of American Literature and Civilization, Université de Rouen Normandie. She is on the Roster of American Literary Scholarship, Duke University and Member of the Advisory Board of The Journal of Contemporary Communication, Open University of Nigeria, Lagos. Her latest publications include: Caryl Phillips, Crossing the River (Atlande, 2017), “The Political Emphasis of Sonia Sanchez” in Sonia on my Mind (University of Michigan Press, 2016), “Media Framing of Political Violence” in Studies in Communication, Mass Media and Society (Abbey Print Ventures, 2015), Ben Okri, The Famished Road, (Atlande, 2013).