Sommaire

4 | 2018

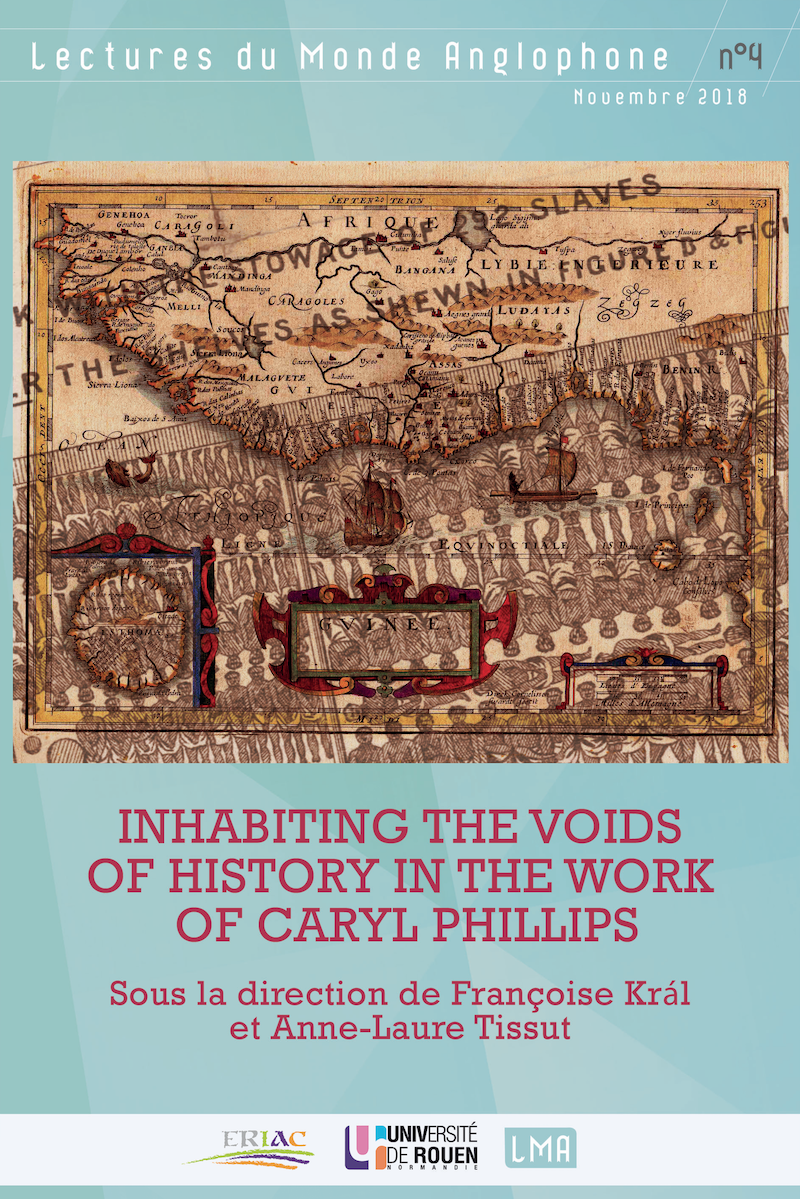

Inhabiting the Voids of History in the works of Caryl Phillips

The present volume proposes to re-read the work of Caryl Phillips through the prism of his engagement with history, both the history of the Middle Passage as well as the unread and unspoken history of lives which have not yet made it into official history. His work can be approached as an invitation to reflect on the role of literature and in particular on the specificity of the literary author with regards to the writing of history and the specificity inherent in handling historical material. More largely this question prompts another issue which is: where does history start, and where does it stop? In recent decades, the rise of subaltern history, women’s history and the histories of minorities has largely broadened the spectrum of what history is about. Absence and loss, mourning and the impossible return are key tropes which haunt the work of Caryl Phillips to the point that the aesthetics which he has crafted over the years seem to weave complex networks of narrative voices which circle voids that are constantly retold, and sounded out. This way of positing the void at the centre is all the more interesting as it constitutes an aesthetic shift from a choice often made in contemporary literature to represent the body, and in particular the wounded body, as a palimpsest of pain which bears witness to the sufferings of the 20th century subject, the post-modern subject and the post-colonial subject. Rather than engage with a thorough and graphic depiction of a suffering body, Caryl Phillips generates a voice which circulates along tangential lines of transmission and prompts the reader to receive and reactivate the salvaged narratives retrieved from archival oblivion. The present volume constitutes a reappraisal of the work of Caryl Phillips up to his most recent novel A View of the Empire at Sunset (2018).

- Françoise Král Introduction

- Kathie Birat Historicising Emotion in Crossing the River by Caryl Phillips

- Justine Baillie “There are no paths in water”: History, Memory and Narrative Form in Crossing the River (1993) and Foreigners: Three English Lives (2007)

- Françoise Clary Extending Intersectionality theory to the perception of Blackness and otherness in Phillipsian social space

- Josiane Ranguin “Happiness is not always fun”: Caryl Phillips’s Crossing the River, part IV (1993) and the BBC Radio Dramatization “Somewhere In England” (2016), Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s Ali: Fear Eats the Soul (1975) and Robert Colescott’s My Shadow (1977) and Knowledge of the past is the key to the Future, (St Sebastian) (1986).

- Giulia Mascoli Spectral Echoes in Caryl Phillips’s The Nature of Blood

- Maria Festa The Nature of Blood and Fragmented History

- C. Bruna Mancini Spaces of memory, identity, and narration in Crossing the River (1993) and A Distant Shore (2003)

- Max Farrar Radical dislocation, multiple identifications, and the subtle politics of hope in Caryl Phillips’s novels

4 | 2018

Introduction

Françoise Král

“I say nothing. There is nothing I can say. You were transported in a wooden vessel across a broad expanse of water to a place which rendered your tongue silent. Look. Listen. Learn. And as you began to speak, you remembered fragments of a former life. Shards of memory. Careful. Some will draw blood. You dressed your fractured memory in the strange words of the new country. Remember? There were no round-trip tickets in your part of the ship. Exodus. It is futile to walk into the face of history. As futile as trying to keep the dust from one’s eyes in the desert.”

(Caryl Phillips, The Atlantic Sound, 21)

1In 1993 Crossing the River was shortlisted for the Booker Prize and won the James Tait Memorial Prize. Ever since this acknowledgement of Caryl Phillips as one of the main voices of contemporary anglophone literature his reputation has continued to grow with the publication of A Distant Shore in 2002, which was awarded the Commonwealth Writers Prize. The present volume proposes to reread his work through the prism of his engagement with history, both the history of the Middle Passage as well as the unread and unspoken history of lives which have not yet made it into official history. His work can be approached as an invitation to reflect on the role of literature and in particular on the specificity of the literary author with regards to the writing of history and the specificity of his handling of historical material. More broadly this question prompts another issue: where does history start, and where does it stop? In recent decades, the rise of subaltern history, women’s history, the history of minorities, to mention only a few examples, has largely broadened the spectrum of what history is about.

2Literature of the middle passage is often defined as texts – novels but also poetry and drama – which engage with the history of slavery and draw their inspiration from slave narratives. Historically speaking, narratives of the middle passage flourished in the United States in the wake of the black consciousness movement and expressed a need to engage with the problematic roots of Afro-American identity (Rushdy) and question the lack of engagement of Western historiography with this episode which constitutes the darker side of western modernity. In Britain some writers, mainly of Caribbean origin, wrote texts which addressed the brutal past of slavery and the Atlantic crossings of slaveships from the 1990s onwards. Among them Caryl Phillips’s novel Cambridge chronicles the journey of an eighteenth century middle class British woman who travels to her father’s plantation in the West Indies and discovers what lies beneath the opulence of the West. Fred D’Aguiar’s novel Feeding the Ghosts engages with the notorious episode of the Zong already immortalized in Turner’s painting Slavers Throwing overboard the Dead and Dying, Typhoon coming on. D’Aguiar’s novel The Longest Memory, is reminiscent of the same motif of fatherly guilt as the plaintive voice of the African father in Crossing the River. In terms of Black British writing, Phillips is a contemporary of another Black writer, Abulrazak Gurnah, originally from Zanzibar, and whose novel Admiring Silence (1996) stresses the need to interrogate official history in search of untold and silenced narratives and in particular the buried vestiges of a brutal and colonial past which one can find in cities like London. Looking at the cityscape his narrator spots “the vestiges of other people’s broken histories”:

Then let your eyes wander farther afield, and there are the factories and warehouses and mechanized farms and model towns and chapels, and museums bursting with booty from other people’s broken histories and libraries sprawling with books congregated over centuries. (Gurnah, 1996, 4)

3Gurnah’s invitation to scan the cityscape for signs of a colonial past reveals the remaining marks left by industrialization as well as the plundered goods acquired through looting and colonial violence. This invitation to unearth fragments and vestiges of a forgotten past is a recurring motif in British Literature of the Middle Passage. D’Aguiar in Feeding the Ghosts engaged in a sort of textual archaeology which maps a trajectory of colonial domination by registering the faintest and most immaterial details, such as the smells of chocolate and tobacco which waft up to the nostrils of his character and whose pleasant fragrances would almost make us forget that they have been obtained through imperial tutelage, colonial domination and slavery.

Simon grabbed the book and ran from Chancery Lane. He jogged towards the docks intent on finding somewhere to hide, not so much himself as Mintah’s journal. He passed coffee houses with crowds spilling out of their doors and a sweet aroma of roasted coffee beans and molasses. Tobacco clouded the air and men puffed on pipes, productive as chimneys. Drunks with rum on their breath stumbled into his path or greeted him as though he were a long-lost friend. He had seen the price of every cup of coffee or dram of rum, every spoonful of sugar, each ounce of tobacco. He reckoned, going by his last voyage on the Zong that if the losses of every voyage of a slave ship were counted, for each cup, each spoonful, each ounce of tobacco, an African life had been lost. (D’Aguiar, 1997, 176).

4D’Aguiar thus opposes the evidence of the written testimony in the form of a slave’s journal to the immaterial and fleeting evidence which envelops the daily lives of inhabitants of 18th century cities where the aromas of chocolate and coffee waft up to the nostrils of the passers-by.

5If the slave trade is central to Crossing the River, it is not only slavery per se which Phillips seeks to address in his novels, but slavery as one of the darkest episodes of history and as part of a longer list of untold narratives which time and the march of history have started to excavate but whose magnitude is still to resonate. Another of these dark episodes of history is the Holocaust, which Phillips engaged with in The Nature of Blood. In his 2003 novel A Distant Shore, he attends to the sorry plight of today’s migrants whose crossing of the Mediterranean provides a dramatic counterpoint to that of the Atlantic in the days of the slave trade. The eponymous section of Crossing the River which imitates the writing of the log of John Newton, the famous slave dealer later turned abolitionist, juxtaposes matter-of-fact listings of slaves written in telegraphic style, with letters to his wife inspired by Newton’s letters to Mary Catlet, published in a volume entitled Letters to a Wife. More than barbarity, it is the coexistence of these two features of one’s personality, of these two moods, and the alternating between indifference and sentiment which Phillips seeks to understand.

6While the aesthetic of Crossing the River is often reminiscent of the generic hybridity and of the art of pastiche which often characterizes post-modern texts, there seems to be more to the chronological unfolding of literary forms which underpins Crossing the River and which range from the epistolary genre, the travel narrative, the adventure story to a novella, a captain’s logbook and finally a series of vignettes which only remotely evoke a diary, as though the fragments had been reorganized afterwards, in a sort of methodological rearrangement of the past and as though the narrative sought to problematize the very notion of chronology, linearity and the writing of history. More than a mere nod in the direction of a postmodern aesthetics of pastiche, the polyptich resonates as though Phillips had decided to try out the various forms available in order to form an Afro-American subjectivity and test the limits so as to present a critique of the inadequacy of such forms (Král, 2017). Read in this light the polyptich sketches an aesthetic journey which experiments first with the dialogic form of the pre-nineteenth century novel in the guise of the 18th century epistolary genre; it then progresses on to a third-person narrative which is focalized through the eyes of the female protagonist, Martha, but which occasionally allows the voice of the protagonist to emerge and be heard.

7One of the lines of inquiry of this volume is to envisage Crossing the River as a pivotal novel in the literary history of the literature of the Middle Passage and to analyse the reasons why the genre has been periodically revisited, from the antebellum slave narratives to the literature of the middle passage in Britain. These various resurgences of the slave narrative at different points of history have provided new forms for Afro-American and more generally black subjectivity itself to reconfigure its role within modernity but more broadly with other genres of western modernity such as the travelogue or the epistolary genre which served as a framework for some of the subnarratives of the novel.

8This reflexion invites a wider-ranging reflection on the type of interaction and dialogue which literature and history invite. Or to put it slightly more tritely, rather than ask what literature is in relation to history, we could ponder the following: when dealing with historical material, what does literatures do that history does not? Is it merely a case that literature would seem freer to tamper with historical facts and that the willing suspension of disbelief provides more room for fictional unfolding and narrative experimentations? Or could it be that while history requires the citing of sources, literature is not bound to such a strict methodological agenda. Could it also be the case that literature works along the lines of subjectivation while history rejects this category, preferring to stick to the notion of historical truth and subjectivity? This list of partial truths could be extended and yet it would fail to grasp two of the essential points which Caryl Phillips makes in his work, albeit in a very subtle way.

9One of the hypotheses which this volume examines is that the void, the blank and the concave can be viewed as central not only to an aesthetics but also to a politics of the novel. Rather than start from the fullness of the objectifiable fact and its factual presence, Caryl Phillips confronts the seminal void which pre-exists literary creativity – the loss of the homeland, the loss of a child and the loss of life, the loss of a narrative of one’s life – before the characters have to embark on a quest which will either never be achieved or which will come too late. Absence, loss, mourning and the impossible return are key tropes of the Phillipsian text, and the whole aesthetics put in place by Phillips aims at weaving a textual web in and around this voice, connecting it, linking it, but never filling it completely. It remains concave, as a void which needs to be sounded out, echoed, retold, remapped and charted so as to link up with external subjectivity. The loss of the narrator’s three children in Crossing the River, which is retold over and over again, echoed not only in the epilogue but throughout Crossing the River, reverberates with the sound of a voice haunted by loss and absence. This echoing void duplicates the departed, placing them in the future rather than simply in the past on a temporal axis.

10This way of positing the void at the centre is all the more interesting as it constitutes an aesthetic shift from a choice often made in contemporary literature to represent the body, and in particular the wounded body, as a palimpsest of pain which bears witness to the suffering of the 20th century subject, the post-modern subject and the post-colonial subject. Rather than engage with a thorough and graphic depiction of a suffering body, Caryl Phillips generates a voice which circulates along tangential lines of transmission and prompts the reader to receive and reactivate the salvaged narratives retrieved from archival oblivion.

11Re-reading Crossing the River in light of Phillips’s handling of these themes in his later works the essays making up the present volume constitute a reappraisal of the work of Caryl Phillips up to his most recent novel A View of the Empire at Sunset (2018).

12In her essay Historicising Emotion in “Crossing the River” Kathie Birat investigates the historical dimension of emotion in the fiction of Caryl Phillips and examines the ways in which Phillips relates the emotional context of the historical periods in which he places his fiction to present day concerns with memory. Birat’s approach draws on the work of historians, like Alain Corbin et Arlette Farge, but also of sociologists, anthropologists, and philosophers to look at the role of emotion in Crossing the River and measure the extent to which the historical relativity and variability of emotion is taken into account by the author in a way that points to an awareness and impact on our capacity to imagine the past.

13In her essay “‘There are no paths in water’: History, Memory and Narrative form in Crossing the River (1993) and Foreigners: Three English Lives (2007)” Justine Baillie attends to the modernist aesthetics of Phillips’s writing. Drawing on Walter Benjamin’s The Arcade Project, Baillie analyses Phillips’s writing and in particular the “literary montage” in the opening of Crossing the River as characterized by a narrative move that belies the continuities of the Enlightenment project and its civilizing proclamations. Baillie analyses how Phillips returns to, yet also inverts, Conradian modernism; rather than approach history in Enlightenment terms, as progressive continuity, Phillips’s elliptical, disjointed and juxtapositional narratives illuminate time and space in ways that correspond with Benjamin’s “constellation” of unfixed points, both vanishing and re-emerging.

14In her article “Extending Intersectionality to the perception of Blackness and Otherness in Phillipsian space” Françoise Clary contends that the perception of blackness and otherness in Phillipsian social space is best understood by referring to what is most important about intersectionality theory, its insight that identities are a compound of overlapping elements. Clary’s essay focuses therefore on the dialectic established by the narrator of Crossing the River between a number of shifting levels of vision that reflect an acceptance of hierarchies of identity – then disclaim these hierarchies, analysing more specifically, the way empowerment is to be understood as the key unmasking device, as evoked by Kimberle Crenshaw. The article also extends intersectionality theory to the perception of blackness and otherness in the collection of essays Colour me English, with the purpose of showing how race and class, or race and culture overlap while highlighting the ways in which their multiple interactions contribute to create additional forms of subordination.

15Josiane Ranguin’s article “‘Happiness is not always fun’: Caryl Phillips’s Crossing the River, part IV (1993) and the BBC Radio Dramatization ‘Somewhere In England’” (2016), Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s Ali: Fear Eats the Soul (1975) and Robert Colescott's My Shadow (1977) and Knowledge of the past is the key to the Future, (St Sebastian) (1986)” engages with the motif of doomed mixed-race couples through a convergence between Fassbinder’s film and the work of Caryl Phillips. Her essay, which adopts an intermedial focus, repositions this motif within a larger tradition of depiction of mixed-race couples and analyses the work of Phillips as “emotional repair work”.

16In her essay “Spectral Echoes in Caryl Phillips’s The Nature of Blood”, Giulia Mascoli investigates a feature of Phillips’s writing which is often-mentioned by critics whilst having been too rarely analysed in article-length studies and which is the musicality of Phillips’s writing, or rather the connection between music and his prose. Mascoli’s essay offers an interpretation of Phillips’s musical prose so as to explore how the author’s musical stylization can also reflect the two different ways of approaching traumatic experience suggested by Dominick LaCapra’s: “acting out” and “working through” (Writing 21–2, History 54, 104).

17Maria Festa’s article “The Nature of Blood and Fragmented History” analyses the working and meaning of the alternative narration of key historical events which underpins the novel. Festa argues that the fragmented accounts of events and multiple perspectives seem to mirror Phillips’s approach to and understanding of History. Drawing on Michael Rothberg’s concept of history as multidirectional Festa further teases out the workings of history as opposed to memory.

18Bruna Mancini looks at the work of Caryl Phillips through the prism of maps and narrative cartographies, arguing that he seems to be a passionate mapmaker and literary cartographer. Mancini argues that in his texts he depicts and rewrites spaces and places through the eyes of his characters, who in turn reflect (or are rewritten by) them, too. His novels and other writings (theatrical, cinematographical, critical, cultural) draw a rich map of migrations, relocations, voyages, escapes, quests intended to inspect, fill, and reveal the “voids of history”, with its untold stories, silenced voices, lost gazes.

19In the last essay “Radical dislocation, multiple identifications, and the subtle politics of hope in Caryl Phillips’s novels”, sociologist Max Farrar examines the emancipatory politics of Phillips’s writing in a very wide-ranging article which covers Phillips’s entire work. Farrar offers a wide-ranging recontextualization of the politics which underpins the work of Caryl Phillips and sounds out their subtle resonances with the making of British identity today.

Clary Françoise, Caryl Phillips, Crossing the River [2017], Paris, Atlande, “Clefs‑concours”, 2017.

D’aguiar Fred, The Longest Memory [1994], London, Chatto & Windus, 1994.

D’aguiar Fred, Feeding the Ghosts [1997], London, Chatto & Windus, 1997.

Guignery Vanessa, & Gutleben Christian (ed.), Traversée d’une œuvre: Crossing the River de Caryl Phillips [2016], Paris, L’Harmattan, “Cycnos”, 2016, vol. 32, no 1.

Gurnah Abdulrazak, Admiring Silence [1996], London, Hamish Hamilton, 1996.

Král Françoise, Sounding out History: Caryl Phillips’s Crossing the River [2017], Nanterrre, Presses universitaires de Paris Nanterre, 2017.

Phillips Caryl, Cambridge: a novel [1992], New York, Viking Press, 1998.

Phillips Caryl, The Atlantic Sound, New York [2000], Alfred Knopf, 2000.

Phillips Caryl, A Distant Shore, London, Secker and Warburg, 2003.

Rushdy Ashraf, Neo-Slave Narratives: Studies in the Social Logic of a Literary Form [1999], Oxford & New York, Oxford University Press, 1999.

Ce(tte) œuvre est mise à disposition selon les termes de la Licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas dUtilisation Commerciale - Partage dans les Mêmes Conditions 4.0 International. Polygraphiques - Collection numérique de l'ERIAC EA 4705

URL : https://publis-shs.univ-rouen.fr/eriac/428.html.

Quelques mots à propos de : Françoise Král

Université Paris Nanterre

Françoise Král is Professor of English and Postcolonial studies at the University Paris Nanterre (France). Her publications include three monographs in the field of diasporic studies, Critical Identities in Contemporary Anglophone Diasporic Literature (Palgrave, 2009) Social Invisibility in Anglophone Diasporic Literature and Culture: The Fractal Gaze (Palgrave, 2014) and Sounding out History: Caryl Phillips's Crossing the River (Presses universitaires de Paris Nanterre, 2017). She has co-edited two books Re-presenting Otherness: Mapping the Colonial ‘Self’ /Mapping the indigenous ‘other’ in the literatures of Australia and New Zealand (Publidix, 2004) and Architecture and Philosophy: New Perspectives on the Work of Arakawa and Gins (co-edited with Jean-Jacques Lecercle, Rodopi, 2011) and guest-edited an issue of Commonwealth, Essays and Studies, Crossings (37.1 autumn 2014). She is a founding member of the Diaspolinks research network https://www.ed.ac.uk/literatures-languages-cultures/diaspolinks