Sommaire

3 | 2017

Indian Birth and Western Rebirths of the Jātaka Tales

The editors would like to thank the following institutions: for their generous support for this project.

- Michel Naumann, Ludmila Volná et Geetha Ganapathy-Doré Introduction

- Indian Birth and Western Rebirths of the Jātaka Tales

- Naomi Appleton Jātaka Stories and Early Indian Literature

- Neekee Chaturvedi Power, Domination and Resistance: A Subaltern Reading of the Pāli Jātaka Stories

- Subhendu Mund Travelling Tales: Migration, Translation, Adaptation and Appropriation of the Jātaka Katha

- Michel Naumann Marco Polo in Ceylon: A Jātaka written by a Christian

(and some related remarks on Ibn Battuta and Antenor Firmin) - Ludmila Volná Rusalka and « Devadhamma Jātaka »: Water, Water Sprites and New Beginnings

- Rewritings of the Jātaka Tales in Colonial and Postcolonial Texts

- Maria-Sabina Draga Alexandru Jātaka Tales and Kipling’s Commitment to India

- Debashree Dattaray Cultural memory and the birth of a nation: Jātakas in the writings of Gandhi and Rabindranath Tagore

- Nishat Zaidi Partition, Migration and the Quest for Meaning in Times of Moral Crisis: Intizar Husain’s Adaptation of Jātakas in his Urdu Short Stories

- Anupama Mohan The Paradoxes of Realism: Martin Wickramasinghe and The Jātakas in Sinhala Literature

- Geetha Ganapathy-Doré A Fictional Evaluation of Buddhism in Postcolonial Sri Lanka: Manuka Wijesinghe’s Trilogy

- Jon Solomon The Affective Multitude: Towards a Transcultural Meaning of Enlightenment

Artistic Appropriations, Adapations and Variations of the Jātaka Tales

Buddha in New Resurrections: A Comparative Analysis of The Birth of the Maitreya and Buddhas of the Celestial Gallery

Jayita Sengupta

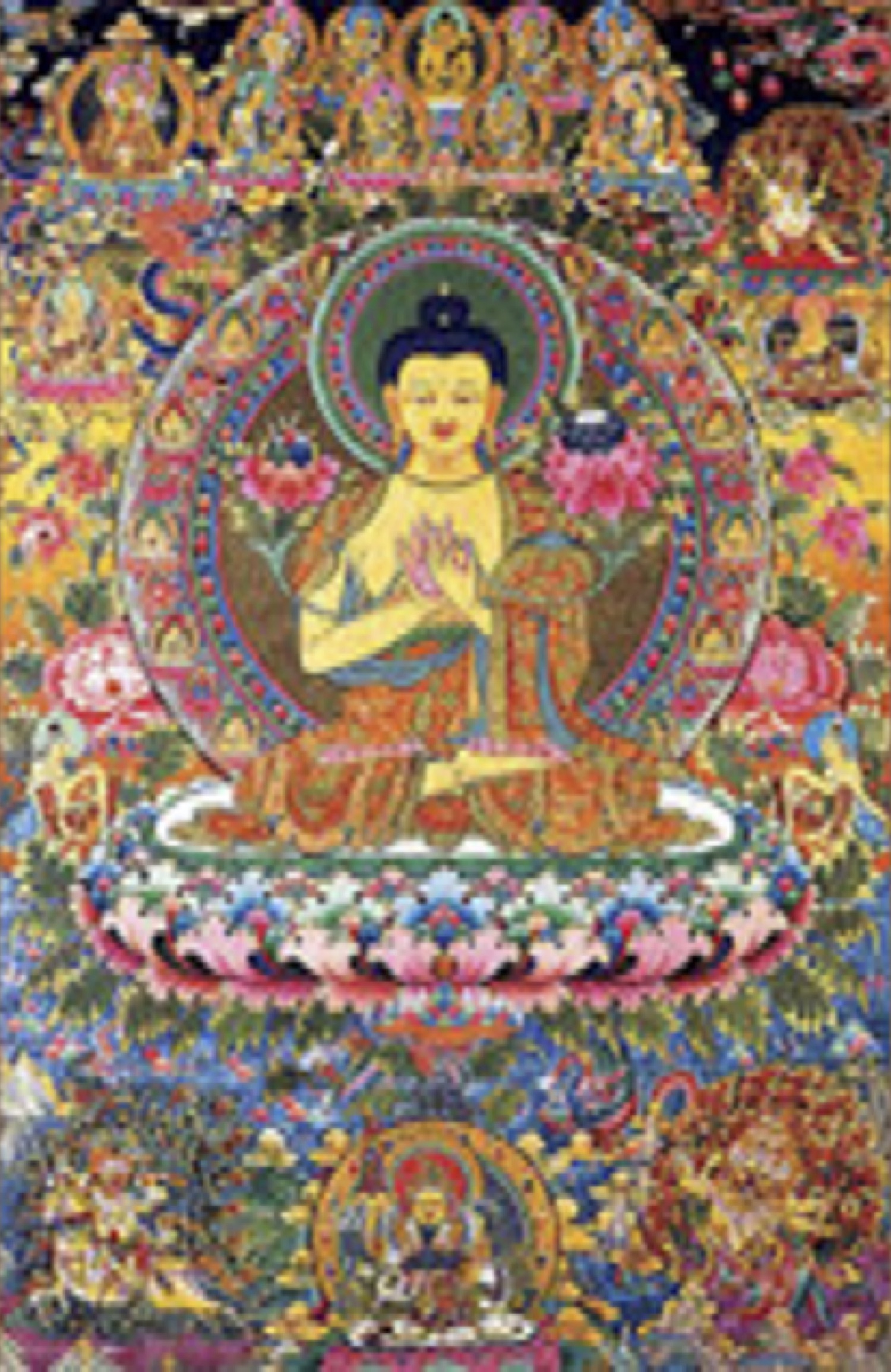

Gautama Buddha has time and again haunted the literary and aesthetic imagination in manifold ways. My intention in this presentation would be to take up two texts: the Bengali modern classic, The Birth of the Maitreya by Bani Basu (in English translation by Sipra Bhattacharya, published by Stree, 2004) which could also be categorized as a historiographic metafiction along with some of the narratives of aesthetic imagination in the thangka paintings by a Himalayan artist, Romio Shrestha in Buddhas of the Celestial Gallery, (published by OM Books International, 2011). The former text, reconstructs Buddha, not as a saint per se, but more so as a man of impeccable diplomatic skills, whose ambition did not allow him to restrict himself as a mere prince of the Sakya dynasty, but to reign the world through the principles of his newly founded religion of Buddhism. The second book, includes narratives of Buddha as a celestial figure. The two texts do take their inspiration from the Maitreya Jataka, and reconstruct the ideal of amity in their own ways, resurrecting the image of Buddha differently. The historiographic metafiction foregrounds an awareness of a Buddha, who had control over the nation, had the royal powers of the divine grace to hold the Jambudwipa together, and inspired to affect the minds of the human race beyond its geographical/cultural boundaries. The narratives of the thangkas by Shrestha, with notes by the Buddhist scholar Ian Baker, intrigue us with the history of a syncretic imagination that is at work, as tantric Buddhist paintings. The purpose of this comparative study of the two different narratives is to unfold the dialogics of a discursive narrative of the Buddha himself as text, appealing to both literary and aesthetic imagination, across time, space and history. Both the texts in their own ways as récit and pictorial narrative offer a rich fare for a cultural studies researcher.

1If Bani Basu’s The Birth of the Maitreya (2007), offers us the political philosophy of amity, the thankas in general, especially Romio Shrestha’s Buddhas of the Celestial Gallery (2011), offer us the spiritual philosophy of amity. While the former is a historiographic metafiction, the latter is metafictional. Again if the récit constructs a postmodernist dialectics of history, the latter is an anti-narrative in its variegated aesthetics. Deriving from Scholes’s « Afterthoughts on Narrative » (1980) in an anti-narrative, events do not follow a chronological pattern. The structure of the narrative is variegated, as it mimics the human memory or creates a pattern of sub-plots which are interlinked in some way or the other. This is the case with the narratives in the thangkas, where the aesthetic representation of religious philosophy has gone through processes of cultural re-formulations, across time, space and regions. So the thankas, following a certain pattern of thought and craft are variegated in their re-presentations by different artists in the Himalayan belt. Even when we take up the art of Romio Shrestha, in the book which has been taken up for selective study here, « amity » itself has a variegated theme, or offers different perceptions and stages of spiritual development.

The récit: The Birth of the Maitreya, history and the concept of amity

2Bani Basu’s text reconstructs the history of Buddha’s life and career in the 6th century BC. It owes its primary inspiration to the Jātakas. But the writer in an interview with me has narrated that her research on the period included several other historical sources and scholarly articles and books on Pali grammar etc. According to the historian, Hemchandra Raychaudhuri’s (2006) research, which has shaped the text’s backdrop, the right of a king to his throne, in those times, was usually legitimized through religious right and genealogies concocted by priests who ascribed divine origins to the rulers. The priests conducted the complex Hindu rituals, and it is surmised that the incipient philosophy in the late Vedic texts and the Upanishads were composed early in this period. While the priestly race and the educated masses spoke Sanskrit, Prakrit was the spoken dialect of the population in northern India. Buddhism as a supplementary religion to existing Hinduism rose with Gautama Buddha’s gaining enlightenment and preaching of his newly founded religion in 537 BC. While Bani Basu’s text has Buddha’s role in the history of ancient India as its primary focus, it actually embodies the vision of « amity » as a political strategy to build a national consciousness and an empire in « Jambudwipa. » Following Raychaudhuri’s argument, the political history in the post-Bimbisara age was split between the centrifugal (love of the local autonomy or the Janapada) and the centripetal (inspiration for imperial unity) forces. The idea of the king as the all-encompassing power figure or as the sole ruler or « ekaqat », possessing all earth and life from one end to the further side of the land bounded by the ocean, was persistent throughout the century. The poets as well as the political philosophers defined the Chakravarti-Kshetra as the thousand « yojanas » or leagues of land that stretched from the Himalayas to the sea as the proper domain of a single universal emperor. Echoing a similar such ideal, the soul of The Birth of the Maitreya, could be etched out in Chanak’s vision in the text:

This empire of Magadha, will gradually spread all over Jambudwipa … somewhere near Rajgriha, an enormous centre of education will come up, similar to Takshashila. Perhaps it will be centred on the dhamma of Tathagatha. (27)

3The novel opens with Chanakya, as a wayfarer from Gandhara. A scholar from Takshashila and as an emissary from the king, Pushkarasari, he is entrusted with the royal duty of bonding the relationship between the two kings of Gandhara and Magadha, so that Gandhara is safe from disturbances caused by the king Prodyot Mahasena of Avanti. As we read on, we realize that the task taken up by Chanakya only provides him with an opportunity to fulfil his larger mission which his father, the Acharya of Takshashila, Debabrata had once voiced to him. He can only mention this to Bimbisara himself at an opportune moment: « Your Majesty, when I first travelled to Magadha, I only remembered my father’s prophecy about this place. “Bimbisara will be Raja Chakravarti, Magadha is the ideal Chakravarti-kshetra” » (53). Debabrata was Bimbisara’s Acharya too at Takshashila. And as history tells us through lady Sumana, Bimbisara’s childhood friend’s recollections, how the ordinary sixteen years old kshetriya boy Seniya lad was anointed a king by his father Kshetranja, on a simple wooden seat covered with a golden lion skin, and how his teacher had re-named him as « Bimbisara », by which he was popularly known later. Bimbisara too recalls his Acharya’s prophecy:

Mount Meru is at the centre of the world, surrounded by endless oceans. On that ocean floats Jambudwipa, like one petal of four petalled flower. There are three more such “petals” amid large seas. This dwipa is surrounded by seas beyond which was land. No one can go as far as the continent of Uttarakaru, and there is no possibility of any attacker coming from there. But from the west, from Apar-Godan, and from the east, Purva-videha, attackers would come in due course. Be that emperor, that sole ruler, who will protect this Jambudwipa. (54)

4On mulling over his Acharya’s words to him, Bimbisara is prompted to re-think the borders of Jambudwipa:

Now tell me Chanak, what is this Jambudwipa? Does it consist of these eastern, central and western states, or does it extend beyond, as far as Balsheek and Bakhtri? Even as far as Sumer and Assura? And the Vindhyaranges? Do they form the southern limits of this land? (58)

5Chanak is apprehensive about these geo-political contours, for Balsheek and Bakhtri do not observe the Vedic way of life. Bimbisara laughs at this skepticism. More conversations, more understanding are required to chalk out their plans for fulfilling the vision of uniting Jambudwipa. This leads them on to the question of war and human sacrifice.

6Bimbisara is weary of war, and Chanakya too cannot fully submit to the Vedic ways of Ashvamedha yojna and sacrifice (in this case, a horse or « asva »). These are the changing times. Vedic ways of life are questioned and contested, and Prakrit gains more popularity than Sanskrit. Chanakya, hailing from the Brahmin family of Chanaks in Gandhar at the personal level, objects to Ashvamedha sacrifice, but he is not able to reject the age old ritual either. He explains to Bimbisara, the social aspect of the yojnas, which brings the noblemen, kings, and princes of the land together. This further brings them face to face with the question of animal sacrifice. War, according to Chanakya, involves human sacrifice. Chanakya craftily points out that Bimbisara, though a follower of Buddha, has to submit to human sacrifices daily by punishing the bandits, traitors, adulterous women. By killing an enemy too, and by suppressing revolts, the king has to move astray from the path of non-violence. Their arguments and counter arguments lead them on to the question: « How is it possible to fulfill the Acharya Debdutta’s prophecy? How to build an empire without war and bloodshed? » (112)

7Two more personalities from history, much lesser known join in the debate. They are Tishya, the son of the local ruler Urgasena in Saket, and Jitsoma, the daughter of a courtesan in Gandhara, who is a scholar, singer, dancer, and excelling in all the sixty-four arts and others, tutored by Chanakya. She is sent as a gift to the king of Magadha, by the king of Gandhara, through various machinations. As history unfolds its hidden secrets, she is also a half-sister to Chanakya. While Tishya, a fellow scholar, much junior though to Chanakya, mulls over a similar vision of « Raj Shangas » and a « Raj Chakravarti », Jitsoma is worried over the practical aspects of kinship. She is asked by Chanakya to rewrite his observations as « Rajshastra », and she takes to the task rather naturally. Jitsoma pens down her own ideas on kinship from her own understanding of politics, though the authorship is originally attributed to Chanakya. Later, in her guise as a courtesan, she performs her duty as a minister to Bimbisara. This is a self-chosen appointment, which Bimbisara has to grant to her at her request, realizing her intellect and her skills.

8Basu’s historiographic metafiction, thus debates a host of issues which ultimately leads to the question of amity and how much of it is desirable and how is it to function? Shades of doubts, aspirations and personal ambitions, create a network of light and shade as Chanakya juggles with the concept of his founding a « Maitreyi » in « Raj Chakravarti » who will found an empire of Jambudwipa. As time moves on, and Tishya and Chanakya set out on their missions to spread the message of amity and « Raj Shangha » in different parts of the country, the affairs of the state of Magadha, begin to complicate themselves. The focus shifts from Bimbisara to Buddha and to the rise of merchant guilds. Money and riches play an important role in maintaining the beauty and grace of the Rajagriha, and the states of Sravasti and Saket. The novel points out how the merchants and their benevolence are important both to the king and to the mushrooming Buddhist Sanghas in the Magadhan empire. They seem to define and refine the role of the Raj Chakravarti. Bimbisara confides to Chanakya:

Chanak, a Chakravarti, an emperor who runs the wheel of fate, maybe of three types: the emperor of four directions, the emperor of the island and the emperor of the region. Of the seven jewels that the emperor must have, I possess all save the Chakra, that is I do possess elephants, horses, jewels, wives, merchant-clan leaders and army commanders. I am in fact the emperor of the region. Though I am yet to find the discus or Chakra that has been described in the Shashtras. And friend, I really cannot understand how a weapon like a discus can magically precede me wherever I go, unless I am endowed with divine powers. (146)

9Possibly, Bimbisara points to the absence of the mystical Chakra, which Ashoka is to found later and establish in the future years of the history of the Magadhan empire. It is only then Chanakya’s vision of the Raj Sangha and Raj Chakravarti is realized. But Ashoka’s reign too is short lived. So the novel, back in time debates on the vision of amity which could hold out for a longer period. What is this larger diplomacy which arises, « out of the deepest concept of heartfelt amity, … which springs from the depths of human virtue … which will not be merely a weapon to preserve one’s narrow interest? »(147). This amity would ask for understanding between races, caste, creed. The « forest dwellers », the non-Aryans pose a problem for the Raj Chakravarti. Bimbisara is at a loss to bring together the various sects and tribes of his empire. He successfully and diplomatically patronizes the Jains even if he is a follower of Buddha. But he is not able to understand the civilization of the hunters, the Yakshas. He is amazed at Chanakya’s argument:

If civilized people who live in huts or palaces, who till lands and domesticate animals for food … can prepare for the human sacrifice, then is it surprising that those who live in forests derive no benefits of Aryan culture, can kill humans? And why should they, therefore, be deprived of the name, “human”? (170)

10The novel argues the definition of civilization through two incidents related to the forest dwellers. Chanakya, the Aryan Brahmin scholar realizes through his experience of a life of a hermit in the forest, that the forest-dwellers enjoy a better civilization than the city-dwellers, for theirs is a life free from avarice. Thus, when Rogga, the girl who had only craved for an ordinary comb from the city, but who is is gifted with a golden one instead and is so delighted with it, comes to the city with her lover Uddak for a visit, she is captured and punished for suspected theft. As the rules of the so called civilized world of the Aryans would have it, Rogga’s ears and nose are cut off and Uddak’s hands are severed from his shoulders. The latter bleeds to death. Or was it shock which killed him? Jivak or the king’s physician cannot be sure. Rogga for certain dies too, when she recognizes Chanakya. The novel records the shame on the civilized world of the Aryans, as Chanakya goes crazy with grief and horror. His cries « Rajashashtra! Shame, shame, shame! » (172) ricochet « through the entire execution ground, and the kingdom, the land of the Bharata, the sea-girdled, sky-crowned earth, and all – all shuddered in shame. » (ibid)

11The friendship between Bimbisara and Chanakya based on amity suffers a severe jolt. Chanakya skeptically analyses, perhaps the sovereign person he has been looking for is NOT Bimbisara. Perhaps it is Gautama. He recounts a previous incident, which justifies his skepticism. The forest dwellers, weary of being treated as demons had started preying on Chandal (Shudras or the lower caste) children at the periphery of the Rajgriha. It so happened that Bimbisara and Buddha were locked in a debate over the issues of non-violence with soldiers joining the Sangha in great numbers. At that time, a yaksha couple intercedes and claims their children. It becomes apparent that the city dwellers had not spared the yaksha kids when they crossed the boundaries of their territory, and sought their vengeance, on the forest dwellers for stealing their own. What interests Tishya and Chanakya in this incident is Buddha’s diplomacy in handling the sensitive issue. As the bereaved mother rushes toward Buddha in her maddening fury, Buddha uses his martial skills, acquired when he was a prince, to avoid her attacks and she falls to the ground. When she demands her children, calling Buddha the sorcerer, Buddha claims the children of the city dwellers, which makes the forest woman, Hariti confess that they had eaten them. There is an obvious cry of grief and anguish from the city dwellers who had come to listen to Buddha’s sermons. They demand their death sentence and Bimbisara orders them to be imprisoned. Yet Buddha asks to gain some time and the forest-woman yells out in her defense:

We do not think of ‘em Ajja folk as persons like us. We don’t. They’ve stolen our forests. They’ve killed off all our animals. Now we have to beg for food. But city-folks close their doors on our faces. They call us, wild! Hateful! Ugly! Terrible! How would I know if these folk love their chillen! (173)

12Buddha draws the king’s and the others’ attention to the woman’s argument. While people are stunned into silence, Ananda, Buddha’s follower walks up to her and speaks to her beseechingly asking why they spared him and not those innocent children. His words of reproach work like magic and Hariti collapses to the ground. Her sorrow of losing her children and the realization of the loss of other mothers of their offspring wear her down. She writhes in pain claiming their children as her own. « We’ve eaten the chillen! We strangled ‘em an’ killed ‘em! Our own chillen! Our own! Our own! » (ibid) Her husband too joins her in her grief. And Buddha turns to Bimbisara, with such words: « O King, there is no need to tie them up or take them to prison! »(173) As Tishya is to analyze, Buddha’s « miracle », could extinguish the fire of anger in the tide of sorrow. « And on the reels of that single sorrow », all his « other personal grief seemed to crowd in » upon his heart. And soon all the sorrows of all the people everywhere mingled with his own « in a single enormous load » (174) which tore at his heart.

13While the city is in turmoil, blaming Bimbisara as weak and giving into Buddha, Chanakya, Tishya, and Jitsoma, rationalize Buddha’s action. Instead of inflicting violence, amity and love could eradicate differences. Buddha has accomplished what Bimbisara could not. He could eradicate all caste barriers; he could accomplish the indomitable task of building a bridge with the forest dwellers and the city dwellers, with his diplomatic vision. His Sangha was open to all. Yet, the question remains unspoken in the minds of three: If all were to turn to the ways of Buddha, who will defend the kingdom? Suppress revolts? How was it possible to provide protection and yet not resort to violence and build an empire? Three types of thought haunt these three men. Chanakya visualizes an enormous army, as vast as the sea, composed of foot soldiers, horsemen, chariots and war elephants. He envisions the fluttering flags in the wind, bearing the seal of Magadhan empire and that peace reigned. (286) Tishya visualizes that forests have been cleared and dark men with well-muscled chests looked to him, their majesty, for direction. He guides them to their work of building chariots, weaving cloth and cooking in the community kitchen.

14Bimbisara visualizes a scene from his past. An eighteen-year old lad like a flame of light sitting before his teacher and the teacher touching his head and blessing him: « You will be Raja Chakravarti, Bimbisara. » Then the scene changes as he finds before him a serene sandalwood tree (Buddha) with a thundering voice: « From the moment of birth, man is tied down by hundreds of bonds. At each step, he faces hundreds of hindrances: It would be inhuman to close the door leading to monkhood. » (360)

15Jitsoma pens down her Rajshashtra:

There are three things that kings must be aware of: danger from the enemies outside the state, danger from enemies within the court and danger from their own selves. (357).

16Jitsoma, the courtesan, the minister, the scholar who actually pens the Rajshashtra, is a prey to Bimbisara’s son’s lust. While Bimbisara treats her with respect, he is not able to protect Soma from the willfulness of Kuniya and fails to keep Chanakya’s promise. Jitsoma, caught in the web of complications in « Rajneeti », and Kuniya’s amorous advances, has to work out her own salvation. She is the one who, while supporting Bimbisara with her friendship, predicts his downfall. Bimbisara is the one who had wanted to give his kingdom to Tathagata. If he is unable to do that, for the latter’s refusal to the offer, he gives Tathagata, the power to spread his message of non-violence and amity at the price of creating enemies. He might be valorous, but he is too soft in mind as Chanakya had thought so in their first meeting: « Affection, love, compassion, pity, all human qualities were present in Bimbisara’s personality. Chanak felt that the king needed to have a hard, steely person close to him. »(72) Perhaps it is this affection, which led Bimbisara to rear a spoilt son, Kuniya in whose hands lay his downfall and his life. Perhaps the amity as a philosophy had its loopholes. So Buddha too is skeptical and weary with the functioning of the Sangha. Guilt sweeps over him, as he stands on the peak of Griddhrakuta, at the break of dawn. If Tathagatha cannot see Bimbisara, at least Bimbisara could, from his solitary prison window. It becomes clear to Bimbisara, at that instant, where his fault lay. « His fascination with Tathagatha, was the action, the karma, the result of his imprisonment … there was no power … which could bring about change. » (468)

17Tishya, later married to Jitsoma, and performing his task as an envoy of Bimbisara, realizes that their dream has only turned to ashes. He is murdered slyly by Birurhak, the king of Kosala, who had feared that Tishya’s popularity among his subjects at Kosala and at Sravasti might stand in the way of his ambition. In the hour before Tishya meets his fate, he sums up the saga of the lives which had met and which had shared a common dream. Chanakya exiled, Bimbisara dethroned, and Tihya is left to his own devices.

Each precious life began its journey with such strong self-belief! Then one day there was no turning back, one realized that somewhere along the way, one had lost the goal. That nothing much has been achieved. (488)

18Tishya too blames Tathagata:

This murder of Bimbisara would not have taken place, if he had not come along with this message of non-violence, for the city the citizens of Rajgriha, down to the meanest man, had desired the splendor of imperial rule.. . . But perhaps if not for this Sakya sage … Magadha and Kosala might have formed an enormous state, in the spirit of amity. Perhaps the union of kings might have taken place. (488)

19Tishya imagines a form, created from the essence of all living creatures–man, beast, bird and plant. He imagines this form, which could be interpreted as his desire for amity, trying to break through the iron walls of ever-changing Time.

20As Jitsoma moves back to Gandhara, then a province of the Persian king, Dariavaush or Darius I, she feels that the right place for Tishya’s son and hers to grow up is in Chanakya’s own land. He would begin a new line of Chanakya’s, for, « what if a genius born of this line in the distant future, could understand Chanakya’s dream of liberty … could break the shackles someday? » (490) Tathagatha too admits, « I have done what I could … when after 5000 years, the influence of this true dhamma will have vanished without a trace, another Buddha will appear–the Maitreya. » (491) The words remind us of another prophecy: the Words of Nostra Domus: « And there would rise a saint from the East » to build a kingdom of peace. A kind of solace it has to offer to us who have become so accustomed to terror, bloodshed rocking the very foundation of human civilization every day. Perhaps as the writer contends, in a discussion with the researcher (2011) « Maitreyee is not a person but the embodiment of an idea out of experiments and experiences. Perhaps it is a utopian dream. »

Thangkas and Romeo Shrestha’s celestial gallery foregrounding amity

21The thangkas connect with the utopian dream of amity, the note in which Bani Basu’s text ends. They offer a variegated theme on the subject, as projected through the process of transnationalism and transculturalism, across time and space. The comparative and interdisciplinary analysis taken up in this research follows from the argument put forward by Ann Brooks, who points out,

Transculturalism and transnationalism have produced new conceptions of subjecthood, subjectivity and identity as new cultural and ethnic boundaries have emerged. These new cultural and ethnic identities carry with them the need for new concept-spaces and places from which to speak. This emphasis requires a transdisciplinary approach to the analysis of representation and identity. (Edwards 184)

22Thangkas as anti-narratives of cultural cognition are metafictional for they ultimately « force us to draw our attention away from the construction of a diegesis according to our habitual interpretative processes. » (Scholes) They problematize the entire process of narration and interpretation for us. Moving across cultural and national boundaries, these religious scroll paintings are syncretic in nature and render the concept of amity, peace, and enlightenment from variegated perception and imagination, picking on cultural metaphors from regions through which they have travelled. So these scrolls of creative borrowing and absorption are at once sacred and have an aesthetic appeal of their own. The art of the thangka making originated from the Indian cloth painting tradition called the « patachitra », used by itinerary storytellers. These sacred paintings draw their inspiration from the cloth paintings of Central Asia, Nepal, and Kashmir. In their treatment of landscape, the Chinese influence appears rather poignant. A Thangka according to the definition in encyclopedia denotes « something rolled up. » According to Tucci, « Thangkas are paintings of sacred and ceremonious subjects, which are hung up in temples or private chapels, or carefully rolled up to be carried over the shoulder when travelling, for the divinity lodged in the painting saves the bearer from the perils of his journey » (1967: 106). The word « thangka », owes its source to the Tibetan “thang yig” meaning « annal » or « written record. » Thangkas originated in India and evolved, and then travelled to Tibet, absorbing along the way the nomadic lifestyle of early Buddhist monastics. The wandering monks traveled extensively to outlying areas to spread the teachings of Buddha. Everything they needed and used traveled on the backs of yaks, including tents, furniture, and paintings. Again for Tibetans, these scroll portraits depicting esoteric experience from Tantric Buddhism merged with Lamaist principles and personified scriptures having a strong sense of the visionary in the artist who created them. The purpose of these paintings was to invoke the aesthetics of a bodily sacred and serve as icons to be worshipped as visual aids to meditation. While Tibet majorly nourished this Lamaist art, the artistic traditions of other neighbouring countries like Nepal, Bhutan, China, and India merged and mingled in this art form along with ideas in philosophy and religion and re-spread into China, Central Asia, Mongolia, Nepal, India, and Bhutan. The process of ideas travelling with people, philosophy and religion, following Said’s concept of « Travelling Theory » have been dialogical and diachronic across historical/geographical space and time. Romeo Shrestha’s creations, however, choose the theme of Buddha in his enlightenment along with the deities in Tantric Buddhism with their significance. The themes, in the « celestial gallery » with their technicalities and colour symbolism, go into the making of these sacred scrolls. They offer a fine spiritual aesthetics which are an embodiment of the syncretic process of the cultural history of Lamaism absorbing Tantric principles of the Buddhism from India. As the principles of Tantric Buddhism would have it, these thangkas do not question the role of Buddha as the spiritual master or Boddhisatva, who is also a Boddhichitta. If Bani Basu’s text re-creates the ambition of Gautama Buddha to rule the world through his founded religion, the thangkas re-present him as a saint. They offer a Boddhisatva cult, through human imagination and art. Romio Shrestha’s book of Thangka paintings open with a painting of Buddha, as the masculine-feminine principle at the centre of a temple like structure reminiscent of the ratha, or chariot in Pemangyetse monastery, with a caption, « Our body is made up of thousands of temples. » (Fig. 1)

Fig. 1 – “Our Body is made up of a Thousand Temples”.

23The concept of the ardhanarishwara is implicit here, in the figure of the Buddha. The Boddhicchitta, suggesting that creativity is divinity and that creativity is possible when the body itself is illuminated through the power of the mind with the sacred light of a thousand temples. The painting reminds one of a Tagore song, « Mandir –e momo- ke/ ashiley hey/shokolo duwaro aponee khulilo/ shokolo prodeep o aponee jwolio/ », or the song by Swami Yogananda, a friend of Tagore, who derived his inspiration from this song, to write his own, which is a close (but not exact) translation of Tagore’s lyrics into English:

Who is in my temple?

All the doors do open themselves;

All the lights do light themselves;

Darkness, like a dark bird,

Flies away, oh flies away. (2014 edition: 9)

24or

In my house with thine own hands

Light the lamp of thy love! (Ibid: 29)

25This book of Thangka paintings by Romio Shrestha, contains about thirty-five paintings, with commentary by the art historian, Ian Baker, who has lived in Kathmandu for twenty-five years and has been in close association with Dalai Lama. While it is not possible to analyze all the paintings, placing them in the domain of tradition and individual talent, two could be selected for deliberating on the question of amity, peace, love and liberation. Romio Shrestha derives his inspiration from the Tibetan and Nepalese tradition of Tantric Buddhism for his paintings. The painting titled « Spinning the Truth » is about the figure of the « Maitreya » or the future Buddha or « Vairochana » in « dharmavyakhyana » mudra (gesture of turning the wheel of law), seated on a Lotus throne. But he also holds the Lotus in between his palms in the mudra. The typical iconography of Vairochana could be found in many sculptures and paintings, say for example the sculpture in the Buddha Park, Ravongla, Sikkim, which could be compared to Shrestha’s imagination.

Fig. 2 – Buddha Park, Ravongla, Sikkim

26In this sculpture, right below the Maitreya Buddha’s altar is the Dharma Ratna or the three jewels in secret teachings by Buddha, which is part of the Mahayana iconography, comprising the dharma chakra with “mriga” (deer) on either side and guarded by the serpents or “nagas”. It is known that Nagarjuna had his source to Buddha’s transcendental knowledge from the serpent world. In Sikkim and other Himalayan regions, the serpents look more like dragons, owing to ethnographic and anthropological histories. But as Sangs-Rgyas1 warns us these serpents are not dragons, for in Tibetan there is a different name for the same. While this sculpture follows the Mahayana iconography, Romio Shrestha’s paintings develop a style of their own, emulating from the vast tradition of Mahayana and Vajrayana iconography, which the artist-monk’s perceptive mind and imagination might have captured to culturally cognate and creatively lead to meditative visions put to paint.

Spinning the Truth (Shrestha 21)

Fig. 3 – Romio Shrestha, p. 21.

27In this painting, (See Fig. 3) the two lotuses stemming from Buddha’s hand in dharmavyakhyana mudra, hold the bowl of ambrosia on his right and the bowl of alms on his left. The various figures around the Maitreya figure are the various visions, transcendental experiences attained through meditation, manifested through the wrathful, erotic, peaceful and archetypal embodiments of the awakening of human consciousness. True to the Vajrayana principle, « remaining transparent to both desire and terror alters the fundamental nature of experience, and by extension reality itself. » (Shrestha 21).

The Neurology of Love (Shrestha 38)

Fig. 4 – The Neurology of Love

28This painting foregrounds the androgynous Buddha, Avalokiteshvara, rising from the lotus of the heart, representing universal peace and love. The classical Buddha overhead, suggests the essence of enlightenment. There are two Taras, the white and green, by the two sides of Avalokiteshvara. While the white Tara stands for « she who grants long life and wisdom », the green Tara is the « beloved saviouress. » As the legend would have it, Tara was born from the compassionate tears of Chenrezig or Avalokitshvara. Mara’s dragons in the painting make an attempt to deflect Avalokiteshvara’s focus from the welfare of all sentient beings ineffectually. Avalokiteshvara holds in his palms joined together close to his heart, a wish-fulfilling jewel. In his two additional hands there is a lotus blossom and a crystal rosary. The paired Boddhisatvas, Manjushree for wisdom and Vajrapani, for all transcending awareness, assist the maitri Buddha. The Buddha deity is invoked through his six syllabic mantra, « OM MANI PADMA HUM », to amplify the power of the healing energy of love and peace or « maitreyi » which is fundamental to human nature.

29Deities such as these exist in numerous forms, and are classified as meditative deities, or guardian deities. The deity of Maitreyi or compassion is actually the state of mind. The image in Romio Shrestha’s imagination reproduced through the thangka, has a spiritual significance. It allows us to see things in a positive manner. As Romio Shrestha writes as a caption to his thangka, « With compassion and love we can free ourselves from the entanglement of the illusory worlds. »(38) Ian Baker in his commentary includes that a research conducted by the Buddhist monks, reveals significant effects of meditation on neuroplasticity, or the mind’s capacity to alter the physical shape and circuitry of the brain. Ian Baker points out,

The brain’s innate plasticity means that desirable changes can be directly facilitated, from the internal regulation of thoughts and emotions, and reduction of physiological stress, to the activation of dormant neural circuitry and cognition. Although the neural correlates of subjective interior states can suggest materialistic conceptions of consciousness, they can’t ultimately account for the rarefied awareness and transcendent acts of loving-kindness at the heart of all genuine spiritual life. (ibid)

True to the principles of all the four schools of Vajrayana or Tantric Buddhism, emancipation and enlightenment is possible not by suppressing the negativity within, but by « experiencing them in the greater light of relaxed, non-conceptual awareness and the spontaneous, and ultimately immeasurable, reality of fully awakened consciousness ». (ibid)

30In conclusion, it can be said that what the récit in Basu’s text has proposed, the thangkas exemplify. The concept of the « Maitreyi », is explored ad infinitum in these paintings, through the imagination and perception of the artists. Romio Shrestha refers to himself as the seventeenth reincarnation of the master thangka painter Arniko. As a drop out monk, who takes up the vocation of an artist, he embodies the philosophy of the vajrayana cult as a seer in his own right across the world. His thangkas as an embodiment of the idea of peace, amity, compassion and enlightenment are examples of aporetic temporal experiences in art and spiritual philosophy. As cultural texts, they also include recursion or reiteration of patterns of experiential reality aesthetically constructed to offer knowledge beyond the entrapping s of the material to codify the « gnomon » (sundial) or affect a re-cognition of the « epiphanies » or « bodhisattvas » through the practice of Vajrayana Buddhism. So the historiographic metafiction majorly based on the Theravada tradition and using the Maitreya Jātakas and giving a political twist to the theme of amity reconstructs a different Buddha. Bani Basu’s text foregrounds the flesh and blood person that Gautama Buddha was, with the dream of ruling the minds of the world through his philosophy of amity. An ordinary conquest of a kingdom and Raj chakravarti kheshtra was not enough for his soaring ambition. The thangkas, later through the sacred aesthetics only subscribe to his dream. So Buddha himself and his philosophy become the embodiment of an idea, a transcultural, transnational concept which any soul in this trouble-ridden world of wars, divides and border conflicts would cherish as his spiritual quest for peace and enlightenment.

Basu Bani, The Birth of the Maitreya, Kolkata, Stree Publishers, 2007.

Brooks Ann, « Reconceptualizing Representation and Identity », in Iim Edward (éd.), Cultural Theory, Los Angeles/London/New Delhi/Singapore, Sage Publications, 2007, p. 183-230.

Farkas E. Richard, Elements of Tibetan Buddhism, Delhi, Fundation Books, 2013.

Yogananda Pramahansa, Cosmic Chants, Kolkata, Yogoda Satsang Society of India, 2014 [2003].

Raychaudhuri Hemchandra, Political History of Ancient India, New Delhi, Cosmo Publications, 2006.

Samuel Geoffrey, The Origins of Yoga and Tantra, Cambridge/New York, Cambridge University Press, 2008.

Santiago José Roleo, Thangkas: The Sacred Painting of Tibet, Delhi, Book Faith India, 1999.

Sarma Saguna, The Tibetan Thangka, Gangtok, Sikkim Research Institute of Tibetology, 2002.

Scholes Robert, « Language, Narrative and Anti-Narrative », Critical Inquiry, 1980, vol. 7, no 1, p. 204-212.

Sinha Nirmal C., Tales The Thangka Cell, Gangtok, Sikkim Research Institute of Tibetology, 1989.

Stong Sangs-Rgyas, An Introduction to Mahayana Iconography, Gangtok, Sikkim Research Institute of Tibetology, 1988.

Shrestha Romio, Buddhas of the Celestial Gallery, Noida, OM Books International, 2011.

Tucci Giuseppe, Tibet: Land of Snows, New York, Stein and Day, 1967.

1 Sangs-Rgyas Stong, An Introduction to Mahayana Iconography, Gangtok, Sikkim Research Institute of Tibetology, 1988, p. 23.

Ce(tte) œuvre est mise à disposition selon les termes de la Licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas dUtilisation Commerciale - Partage dans les Mêmes Conditions 4.0 International. Polygraphiques - Collection numérique de l'ERIAC EA 4705

URL : https://publis-shs.univ-rouen.fr/eriac/200.html.

Quelques mots à propos de : Jayita Sengupta

Independent Scholar

Jayita Sengupta is an academic. She was a British Council Fellow in 2000, a Senior Fulbright vising faculty at Stanford University and in Taiwan universities in 2013. Her research interests include Cultural Studies, Creative Writing and Translation. She has taught in various colleges in Calcutta and Delhi and in a central university, in India, and has several books, translations and research publications to her credit. She is the founder member of a non-profit organization devoted to Liberal Arts, namely Caesurae Collective Society and is the Managing and Chief Editor of the multi-media, peer reviewed international e-journal, Caesurae: Poetics of Cultural Translation (www.caesurae.org), associated with the organization. Her publications include Barbed Wire: Borders and Partitions in South Asia (Routledge, 2012). Her English translation of Gandharvi: Life of a Musician (Orient BlackSwan, 2017) will be of interest to scholars researching on Indian classical music, narrative, gender issues and history of 1960s Kolkata. She is presently working on her debut novel and a volume near completion on « Narrative Explorations of History, Memory and Time ».